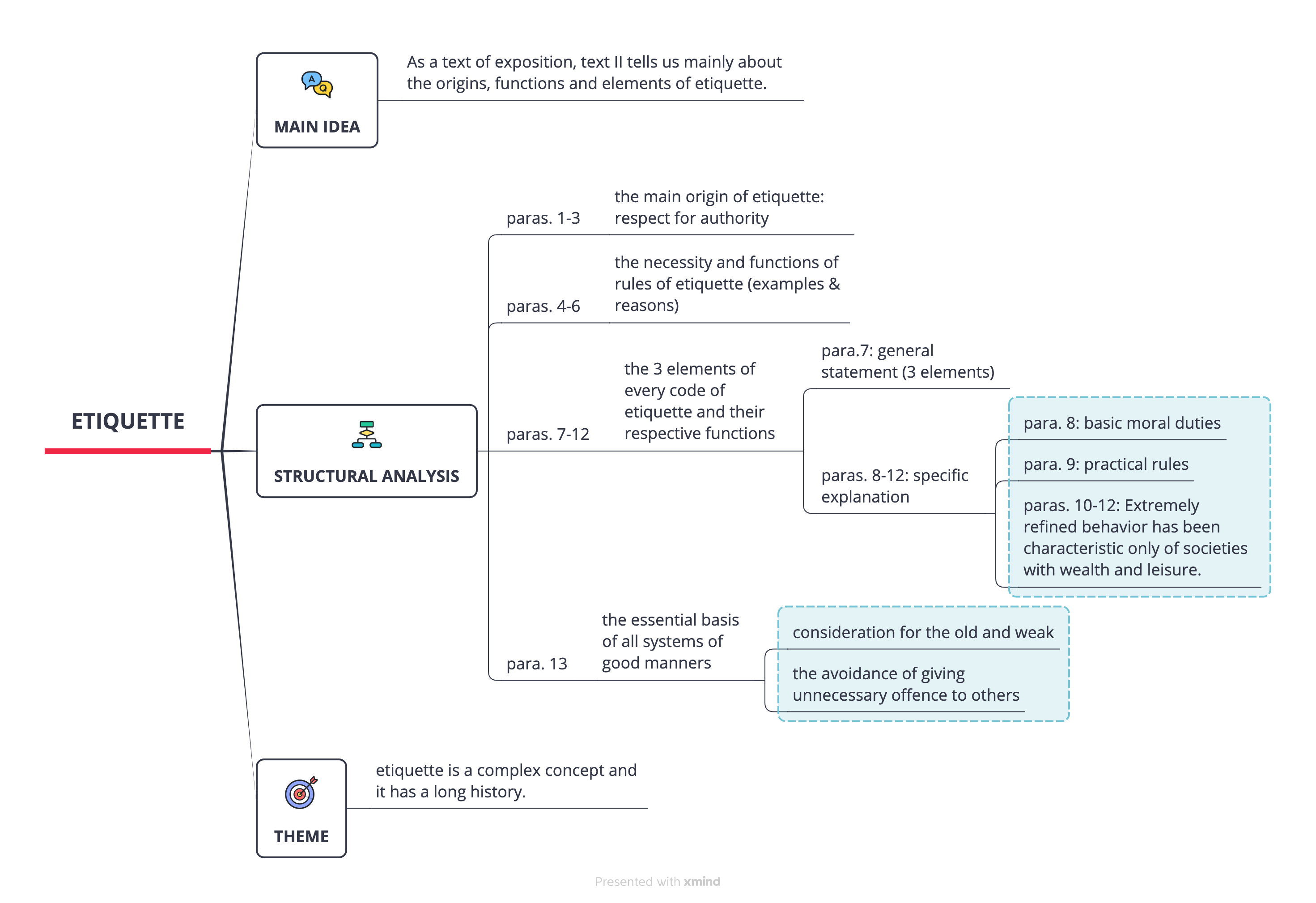

Text II

Lead-in questions

1. How do people behave properly in public? Give one or two examples to illustrate it.

2. What do you know are the proper rules of etiquette in the classroom?

Text

Etiquette1

1 The origins of etiquette, the conventional rules of behavior and ceremonies observed in polite society, are complex. One of them is respect for authority. From the most primitive times, subjects showed respect for their ruler by bowing, prostrating themselves on the ground, not speaking until spoken to, and never turning their backs to the throne. Some monarchs developed rules to stress even further the respect due to them. The emperors of Byzantium 2 expected their subjects to kiss their feet. When an ambassador from abroad was introduced, he had to touch the ground before the throne with his forehead. Meanwhile the throne itself was raised in the air so that, on looking up, the ambassador saw the ruler far above him, haughty and remote.

2 Absolute rulers 3 have, as a rule, made etiquette more complicated rather than simpler. The purpose is not only to make the ruler seem almost godlike, but also to protect him from familiarity, for without some such protection his life, lived inevitably in the public eye, would be intolerable. The court of Louis XIV of France 4 provided an excellent example of a very highly developed system of etiquette. Because the king and his family were considered to belong to France, they were almost continually on show among their courtiers. They woke, prayed, washed and dressed before crowds of courtiers. Even larger crowds watched them eat their meals, and access to their palaces was free to all their subjects.

3 Yet this public life was organized so minutely, with such a refinement of ceremonial, that the authority of the King and the respect in which he was held grew steadily throughout his lifetime. A crowd watched him dress, but only the Duke who was his first valet de chamber5 was allowed to hold out the right sleeve of his shirt, only the Prince who was his Grand Chamberlain could relieve him of his dressing gown6, and only the Master of the Wardrobe might help him pull up his breeches.7 These were not familiarities, nor merely duties, but highly coveted privileges. Napoleon recognized the value of ceremony to a ruler. When he became Emperor, he discarded the revolutionary custom of calling everyone ‘citizen’, restored much of the Court ceremonial that the Revolution had destroyed, and recalled members of the nobility to instruct his new court in the old formal manners.

4 Rules of etiquette may prevent embarrassment and even serious disputes. The general rule of social precedence is that people of greater importance precede those of lesser importance. Before the rules of diplomatic precedence were worked out in the early sixteenth century, rival ambassadors often fought for the most honorable seating position at a function. Before the principle was established that ambassadors of various countries should sign treaties in order of seniority, disputes arose as to who should sign first. The establishment of rules for such matters prevented uncertainty and disagreement, as do rules for less important occasions. For example, at an English wedding, the mother of the bridegroom should sit in the first pew or bench on the right-hand side of the church. The result is dignity and order.

5 Outside palace circles, the main concern of etiquette has been to make harmonious the behavior of equals, but sometimes social classes have used etiquette as a weapon against intruders, refining their manners in order to mark themselves off from the lower class.

6 In sixteenth-century Italy and eighteenth-century France, waning prosperity and increasing social unrest led the ruling families to try to preserve their superiority by withdrawing from the lower and middle classes behind barriers of etiquette. 8 In a prosperous community, on the other hand, polite society soon absorbs the newly rich, and in England there has never been any shortage of books on etiquette for teaching them the manners appropriate to their new way of life.

7 Every code of etiquette contains three elements: basic moral duties; practical rules which promote efficiency; and artificial, optional graces 9 such as formal compliments to, say, women on their beauty or superiors on their generosity and importance.

8 In the first category are considerations for the weak and respect for the aged. Among the ancient Egyptians the young always stood in the presence of older people. In Tanzania, the young men bow as they pass the huts of the elders. In England, until about a century ago, young children did not sit in their parents’ presence without asking permission.

9 Practical rules are helpful in such ordinary occurrences of social life as making proper introductions at parties or other functions so that people can be brought to know each other. Before the invention of the fork, etiquette directed that the fingers should be kept as clean as possible; before the handkerchief came into common use, etiquette suggested that, after spitting, a person should rub the spit inconspicuously underfoot. 10

10 Extremely refined behavior, however, cultivated as an art of gracious living, has been characteristic only of societies with wealth and leisure11, which admitted women as the social equals of men. After the fall of Rome12, the first European society to regulate behavior in private life in accordance with a complicated code of etiquette was twelfth-century Provence 13, in France.

11 Provence had become wealthy. The lords had returned to their castles from the crusades, and there the ideals of chivalry grew up, which emphasized the virtue and gentleness of women and demanded that a knight should profess a pure and dedicated love to a lady who would be his inspiration, and to whom he would dedicate his valiant deeds, though he would never come physically close to her. This was the introduction of the concept of romantic love, which was to influence literature for many hundreds of years and which still lives on in a debased form in simple popular songs and cheap novels today.

12 In Renaissance 14 Italy too, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, a wealthy and leisured society developed an extremely complex code of manners, but the rules of behavior of fashionable society had little influence on the daily life of the lower classes. Indeed many of the rules, such as how to enter a banquet room, or how to use a sword or handkerchief for ceremonial purposes, were irrelevant to the way of life of the average working man, who spent most of his life outdoors or in his own poor hut and most probably did not have a handkerchief, certainly not a sword, to his name. 15

13 Yet the essential basis of all good manners does not vary. Consideration for the old and weak and the avoidance of harming or giving unnecessary offence to others is a feature of all societies everywhere and at all levels from the highest to the lowest. You can easily think of dozens of examples of customs and habits in your own daily life which come under this heading. (1136 words)

U2-2 课文朗读打卡:

Words and Expressions

Words and Expressions

段落1

etiquette /ˈɛtɪkɛt/:礼节,礼仪

primitive times /ˈprɪmɪtɪv/:原始时代

bowing, prostrating /ˈbaʊɪŋ, ˈprɒstreɪtɪŋ/:鞠躬,俯伏

Byzantium /baɪˈzæntiəm/:拜占庭帝国

ambassador /æmˈbæsədər/ n. an important official sent by a state as its permanent representative who lives and works in the capital of a foreign country

haughty and remote:being arrogantly superior & disdainful and aloof & unfriendly

haughty /ˈhɔ:ti/ adj. behaving in an unfriendly way towards other people because you think that you are better than them; arrogantly superior and disdainful

subject /ˈsʌbdʒɪkt/ n. a citizen or member of a state rather its supreme ruler 臣民,国民

prostrating themselves on the ground: lying very low with their faces towards the ground, especially as a sign of worship for their ruler or as a sign of willingness to obey their ruler

monarch /ˈmɒnək/ n. a nation’s ruler or head of state usually by hereditary right

Emperor /ˈɛmpərər/:皇帝

段落2

absolute rulers /ˈæbsəluːt ˈruːlərz/:绝对君主

familiarity /fəˌmɪlɪˈærətɪ / n being too friendly and informal for a particular situation过分亲昵; inappropriate and offensive informality of behavior or language 冒犯人的随意、随便

Louis XIV of France :法国的路易十四

courtier /ˈkɔ:tɪə(r)/ n. a noble man or woman who spent a lot of time at the court of a king or queen in former times 昔日宫廷中的朝臣

valet de chamber /væˈleɪ də ˈʃɑːmbər/:侍从

dressing gown /ˈdrɛsɪŋ ɡaʊn/:晨衣

breeches /ˈbrɪtʃɪz/:马裤

段落3

minutely /maɪˈnju:tli/ adv. taking the smallest points into consideration; precisely and meticulously 仔细地,缜密地

Napoleon /nəˈpoʊliən/:拿破仑

citizen /ˈsɪtɪzən/:公民

Grand Chamberlain /ɡrænd ˈtʃeɪmbərlɪn/:大管家

Master of the Wardrobe /ˈmæstər əv ðə ˈwɔːdrəʊb/:衣橱总管

段落4

at a function: at a large or important gathering of people for pleasure or on a special occasion

diplomatic precedence /ˌdɪpləˈmætɪk prɪˈsiːdəns/:外交优先权

seniority /ˌsiːniˈɔːrɪti/:资历

pew or bench /pjuː ɔːr bɛntʃ/:长凳或座位

dignity and order /ˈdɪɡnɪti /:尊严和秩序

段落5

waning prosperity /ˈweɪnɪŋ prɒˈspɛrɪti/:衰退的繁荣

social unrest :社会动荡

barriers of etiquette :礼仪屏障

段落6

chivalry /ˈʃɪvəlri/:骑士精神

romantic love:浪漫爱情

Provence /prəˈvɑːns/:普罗旺斯

段落7

moral duties /ˈmɔːrəl/:道德义务

practical rules:实用规则

optional graces :可选的优雅举止

段落8

considerations for the weak:对弱者的关怀

respect for the aged:尊敬老人

段落9

introductions at parties or other functions :在派对或其他活动中的介绍

fork /fɔːrk/:叉子

handkerchief /ˈhæŋkərtʃɪf/:手帕

段落10

wealth and leisure:财富和闲暇

Rome /roʊm/:罗马

twelfth-century Provence /prəˈvɑːns/:十二世纪的普罗旺斯

段落11

crusade /kru:ˈseɪd/ n. any of the wars that were fought by Christians in Palestine against the Muslims during the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries

virtue and gentleness :美德和温柔

dedicated love /ˈdɛdɪkeɪtɪd /:专一的爱

段落12

Renaissance Italy /rɪˈneɪsəns ˈɪtəli/:文艺复兴时期的意大利

fashionable society :时尚社会

banquet room /ˈbæŋkwɪt/:宴会厅

段落13

avoiding harming or giving unnecessary offence /əˈfɛns/:避免伤害或无谓冒犯他人

customs and habits :习俗和习惯