7.0.2 Models of lexical access

(1)Models of lexical access

How language users recognize a word's meaning—how it should be pronounced or written—is much more impressive skill than it may initially have been realized.Our lexicon must be an extremely organized place in order for speech(or comprehension)to occur as flawlessly as it normally does.The lexicon also serves multiple purposes:when reading,it must yield information on word meaning based on the orthographic(that is,written)representation of a word;when listening to someone,we must recognize words from an auditory code.When we speak or write,words are activated based on the meaning we want to convey,and then translated into a phonological or orthographic code.

A viable model of lexical access must explain how the mind can act like a dictionary and a thesaurus,and a grammar book.Two major classes of models detail how words get accessed(or recognized)during reading or listening.Although they mostly emphasize how words are activated during language activities,these models also implicitly provide us with some hypotheses as to how the lexicon might be organized.

The first type of theory is typically referred to as a serial search model.It claims that when one encounters a word while reading,for example,one took through a lexical list to determine whether the item is a word or not,and then retrieve the necessary information about the word(such as its meaning or grammatical class).Serial search means that the process takes place by scanning one lexical entry at a time sequentially.The best known serial search model is Forster's(1976)autonomous search model.

The second type of model is known as a parallel access(or direct access)model.It proposes that perceptual input about a word can activate a lexical item directly,and that multiple lexical entries are activated in parallel.That is,a number of potential candidates are activated simultaneously,and the stored word that shares the most features with the perceived word wins.Most models then propose some kind of decision stage,during which the accessed word is checked against the input.Among the three major versions of direct-access models,the earliest version is John Morton's logogen model.

Both serial search and parallel access models consider word recognition an automatic process,not subject to conscious examination.That is,one is not cognizant of“searching”through a lexical list or of activating numerous stored words during lexical access.At best,one is conscious only of the end result of these processes—when one realizes that one“knows”what the word is and what it means.

(2)Serial search models

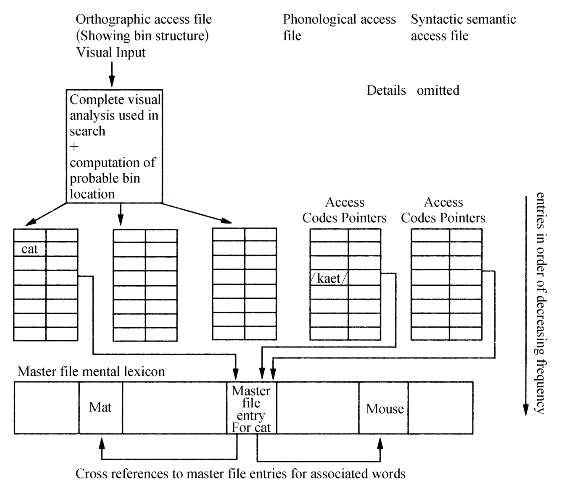

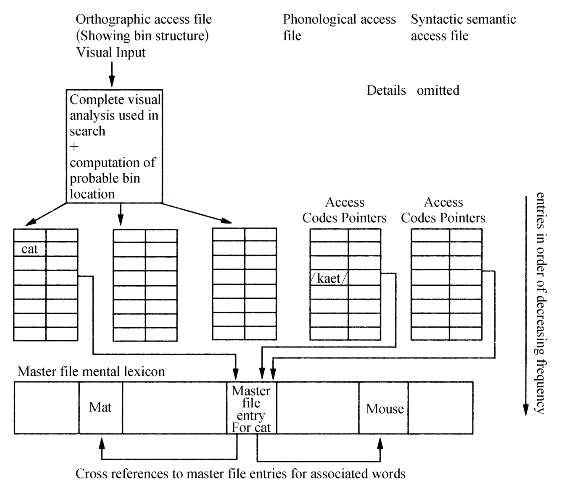

Forster's(1976)autonomous search model of lexical access is best illustrated by comparing the lexicon to a library.A word,just like a book,can be in only one place in the lexicon/library,but its location can be determined from several catalog entries(for example,catalog entries for author,title,or subject matter).In the autonomoussearch model,these catalogs are known as“access files.”Forster(1976)posited three major access filesorthographic,through which words are accessed by their visual features;phonological,through which words are accessed by how they sound;and semantic/syntactic,through which words can be retrieved according to their meaning and grammatical class.Given these three access files,lexical entries can be accessed during reading,listening,and speaking.These access routes can only be used one at a time(just as you can't look up books in more than one catalog at a time).That is,input from any modalities(visual or auditory)can only be used one at a time;it will not speed access time if you hear a word at the same time you read it.The orthographic and phonological access files mostly contain information about the beginning parts of words—the first few letters of their spelling(orthographic)or first few sounds with which they begin(phonological).

When a word is presented either visually or phonologically,a complete perceptual representation of the word is constructed and subsequently activated in the access file based on its initial letters or sounds.When you have derived the location of a word based on its access code(or its index in the library catalog to carry out the library analogy),a search for the word entry in the master lexicon must still be conducted.Thus,Forster's model posits a two-stage process.Just as a person determines which section of the library a book is in,but still must search on the specific shelf,one finds the general location of a lexical entry,but still must search for its unique location in the master lexicon.It is this entry(not the partial entry in the access files)that contains all linguistic information about the word(for example,its meaning,spelling,pronunciation,part of speech).

The master lexicon is assumed to be organized into“bins”or storage units,with the most frequent entries in that bin on the top.This is analogous to putting your books in stacks,with the most frequently used books on the top,and explains why highfrequency words are accessed more quickly than low-frequency words.When an access file directs the search to the appropriate lexical bin,entries are searched one by one until an exact match to the perceptual representation is found.Figure 7.2 depicts how this process takes place.The process of lexical access proposed by sequential search models is thus more of a step-by-step process than that proposed by parallel search models.

When the relevant lexical entry in this serial model is retrieved,it is checked against the input(for example,the written word)in a post-access check.This process is analogous to an automatic spelling checker in a word-processing program.If correct,the search is discontinued.If incorrect,one has two response alternatives:non-words that in no way resemble legitimate words,such as psatu can be confidently rejected.However,nonwords that resemble real words,as coffey resembles coffee,or gallomp resembles gallop,initiate a more exhaustive search.Experiments have shown that more time to reject these legal nonwords is required(sequences that could be words because they follow the phonotactics of English)than one does to accept legitimate words.According to the autonomous search model,the search for a word stops when its lexical entry is located.But in the case of legal nonwords,all possible lexical entries must be scanned before the letter string can be rejected,which delays response time.

Figure 7.2 Forster's Search Model.Source:Forster(1976)

It will be noticed that next attention will be turned to parallel access models.As we shall see,these models explain the various factors that influence lexical access in ways quite different from those proposed by serial search models.

(3)Parallel access models

(a)Logogen model

Morton(1969,1979)proposed that words are not accessed by determining their locations in the lexicon but by being activated to a certain threshold.Thus,a space analogy of lexical access such as one saw in Forster(1976)is replaced with a more electrical analogy—a word will“light up”when its activation is sufficient,in the same way that a lamp lights up when the electrical current is sufficiently strong.How does this activation occur,and what determines the threshold of a certain word?

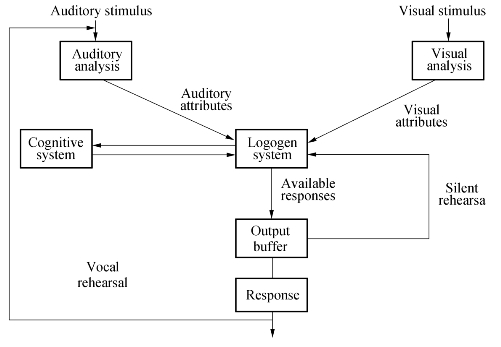

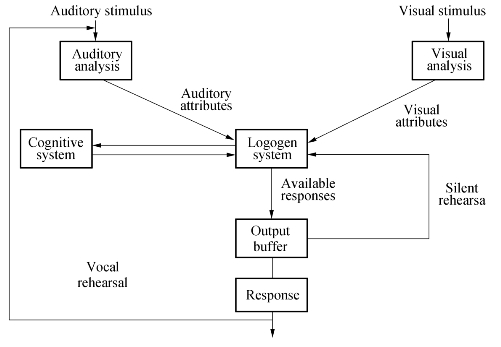

Morton(1969)claimed that each word(or morpheme)has its own“logogen,”which functions like a scoreboard,tabulating the number of features that a lexical entry shares with a perceptual stimulus.When a word is not being recognized,it is said to be in its resting level and has a zero feature count.Each logogen also has an individual threshold,which is the amount of“energy”that will be needed to access that lexical entry.As environmental input arrives when one is reading or listening to language,activation starts to accrue to each logogen based on the orthographic or phonological or semantic information being presented.All available information is accepted and summed in parallel as the various affected logogens race to the finish.Any logogen for which the total activation reaches a predesignated threshold,based on sufficient similarity to the stimulus word,is accessed.If several entries are activated to threshold,the one with the highest count wins and is“recognized”.It then slowly returns to its resting level.The logogen model can thus account for semantic priming by allowing activation from one logogen to spread to related ones,and because it takes some time to return to a zero feature count,the primed target has a head start to recognition.

As depicted in Figure 7.3 Morton's logogen model provides no separate access routes by which to search a master list of lexical item,their subjects make use of all available data—the context of a sentence suggests some meanings over others,the letters used in the orthographic representation of a word activate logogens with those same letter features.And all this information adds up to converge on(usually)a single candidate in the lexicon.Recall that in Forster's autonomous search theory(1976)access routes could be used only one at a time,whereas Morton's initial model permitted simultaneous summation of input from multiple modalities.

Figure 7.3 Morton's logogen model.Source:Morton(1970)

Why,then,high-frequency words easier to access than lowfrequency words?According to the logogen model,frequency effects are the result of the lowered threshold of the stored representation of a frequently used word.That is,it takes less activation to fire a high-frequency word than a low-frequency word.Such a lowering of the threshold takes place over a long period of time.Priming,on the other hand,is accomplished by a quick and temporary lowering of the threshold of the logogens related to a prime.The logogen system itself does not contain semantic or associative data about words.However,when a word is accessed,the cognitive system receives this information and feeds information back to the linguistic system.Logogens that are related associatively or semantically to the prime receive increments to their logogens,and as a result require less perceptual input to achieve threshold.This results in quicker access times for primed words.

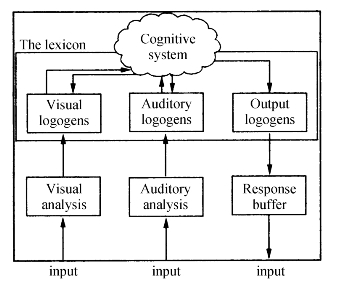

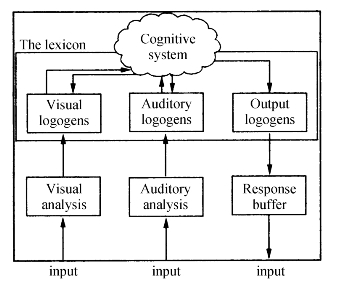

Morton's logogen model was the most influential of the parallel word access models and served as the basis for all of the parallel models that followed.As with any model,however,modifications were made to perfect the system.In order to show how scientific progress forced changes in the model,let's consider the following example.The prediction of the original model that auditory presentation of a word would prime subsequent visual presentation of the same or related words turned out not to be the case,so the logogen model was revised in 1979(Morton,1979;Morton&Patterson,1980)to constrain priming across modalities.Thus,although the model is good at explaining frequency and priming effects,its assumption that perceptual input is summed across modalities to achieve lexical access has been toned down,as suggested by new data.The newest version,depicted in Figure 7.3,posits separate input paths and logogens for words presented in visual channels versus auditory channels.

The initial logogen model also had difficulty accounting for how the linguistic system responds to nonwords.This required a further modification in the model.To ameliorate this problem,Coltheart,Davelaar,Jonasson,and Besner(1977)suggested a deadline within which words are recognized within the logogen system.If a stimulus word is not recognized within this deadline,it is rejected as a legal word.Nonword letter strings that most resemble words,such as coffey,cause more general activation in the logogen system.Such stimuli are rejected later and take even longer to reject than nonwords such as hmrfi,which do not resemble real words at all.

(b)Connectionist models

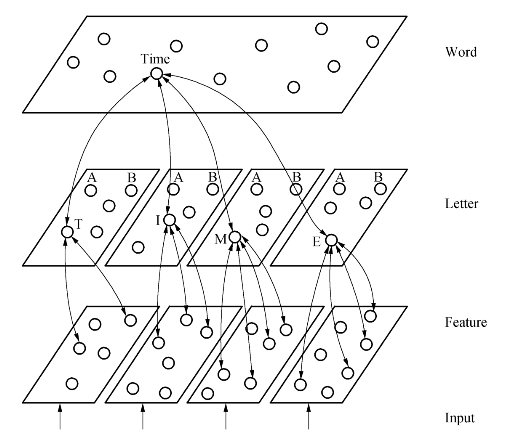

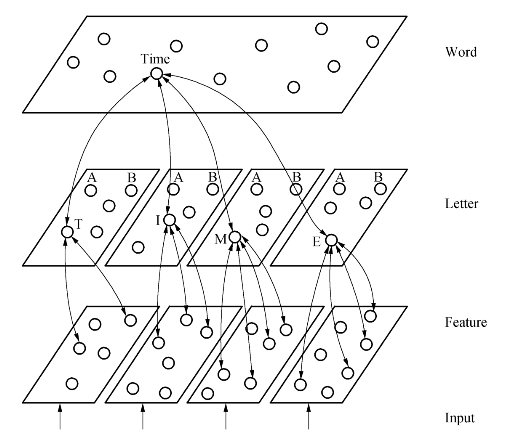

A contemporary cousin of the logogen model comes from what is known as connectionism.Advocates of this approach in psychology,philosophy,computer science,and other fields,known as connectionists,use the analogy of the brain and neurons to develop models of cognition.Their computer models of cognitive processes(such as lexical access)are instituted in“neural nets”composed of nodes and connections between these nodes.There are three types of nodes:input nodes,which process the auditory or visual stimuli;output nodes,which determine responses;and hidden nodes,which perform the internal processing between when we hear and see a word and when we respond to it.The hidden nodes do the lion's share of lexical processing as depicted(in simplified form in Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4 The later version of the logogen model.Nonlexical routes from input to response are shown.Source:(Morton and Patterson,1980)

Connectionist models(for example,that of McClelland&Rumelhart,1981)share many tenets of the logogen model,including direct access to lexical entries,simultaneous activation of multiple candidates,and the use of many types of information to access a target word.However,connectionists are more explicit in defining exactly the cognitive and linguistic architecture—that is,how words are represented.Each functional level of the hidden nodes represents different aspects of words,for example,their visual,orthographic,phonological,and semantic natures,and so forth.Processing proceeds from input to deciphering the raw perceptual input at a featural level(for example,does a written letter have a curved section?);nodes activated here then activate letter units that share those features(for example,P,R,B,G,and so forth),which in turn activate words which share those letters.Figure 7.5 shows how the word time might be recognized in a connectionist model.

Figure 7.5 A sketch of the interactive activation model of word perception.Units within the same rectangle stand for incompatible alternative hypotheses about an input pattern and are all mutually inhibitory.The bidirectional excitatory connections between levels are indicated or one word and its constituents.Source:Mclelland(1985)

Connections between layers,and between nodes in the same layer,can be either excitatory or inhibitory.Excitatory links are those that send activation onto other nodes attached to the original.For instance,if the feature“/”were activated,it would send energy onto all letter nodes that had this feature(for example,A,M,V,W).Inhibitory links,on the other hand,prevent further activation of the linked node.If one recognized the letter A,the letter node for M,V and W should be inhibited so that it does not compete with recognition of the A.The pattern of excitatory and inhibited links allows lower units to feed into higher-level units(for example,letter features must be activated before word units can fire),but units within a layer compete with each other for activation during recognition of a given stimulus.When one representation achieve threshold,it inhibits the firing of similar units with regard to a specific stimulus.

Connectionist models deal with frequency effects in a slightly different way than the logogen model—more frequently used word units have stronger connections to lower-level nodes,such as feature and letter nodes.High-frequency words thus receive more activation when those features and letters are activated.Priming and context effects are also explained the same way:when a node or connection is activated,a spread of activation occurs in all directions,incrementing representations resembling the target visually,phonologically,semantically,and so forth.Connectionist models are also the only lexical access theory to,albeit implicitly,supply a theory of word organization:organization is nothing more than the strength of connections between nodes(either word-word nodes,or word-feature nodes),based on past association.

(c)Cohort model

The cohort model shares basic assumptions about lexical access with the logogen model but was designed to account only for auditory word recognition.Marslen-Wilson(1987)et al.proposed that when one hears a word,all of its phonological neighbors get activated as well.Thus,upon hearing the sentence,“John got a job at the ca-...”candy,cash,candle,cashier,camp,and many others would be available for selection.This set of words is known as the“word initial cohort”(here it refers to a“division”of words).Thus,as in the logogen model,multiple entries may be activated before the system settles on a final candidate.As with the other direct-access models,activation of a word is based on direct communication between the perceptual input and the lexical system.

One difference with the logogen model warrants discussion:rather than the summing of partial inputs to logogens until adequate activation is achieved,all potential candidates for lexical access are activated by the perceptual input and then progressively eliminated.This elimination takes place in one of two ways—either the context of a spoken sentence narrows the initial cohort,or candidates are discarded as more phonological information comes in.In the latter case,as more of the spoken word is recognized,the cohort narrows.For example,if the phoneme/n/was heard after the ca-,candy and candle(plus any other canwords)would be the only lexical items still possible from the initial cohort.The field of candidates continues to narrow as more stimulus information is received until only a single candidate remains.

Initially,the cohort model depended heavily on an exact match between a spoken word and its phonological representation in the lexicon.However,further study determined that people could recognize aurally presented words even if mispronounced,or if a sound(like a cough)blocked out part of the stimulus.The theory was subsequently revised so that the system chooses the best match to fit an incoming word.This also makes the lexical access system less reliant on the word initial cohort.Under the original model,if a word did not make it into the first cohort,it had little chance of being chosen;now,as long as it shares enough features with the auditory stimulus,it can be selected for recognition.

Thus,like the logogen model and the connectionist model,the cohort model of lexical access posits that multiple candidates are activated in parallel.Unlike its cousins,the cohort model states that the list of word candidates is narrowed as the auditory input proceeds serially.It explains frequency and nonword effects in much the same way as the logogen theory.Context or priming is assumed to narrow the original set of candidates,and this shorter initial cohort leads to quicker recognition of a target word.

Having seen how the serial search and direct-access models deal with frequency,word class,phonology,and so forth,can one then determines which of the types of theories is best supported?It turns out that both types of models have something to recommend them.For example,one prediction of the serial search models is that only one access code can be used at a time.This means that hearing a word at the same time you are reading it will not facilitate reading recognition time.

Another test of the two kinds of models relates to the finding of neighborhood effects.Some words have many neighbors that are created by changing only a single letter of the target word.For instance,mail has many neighbors-rail,bail,fail,hail,mall,maid,maim,nail,pail,sail,tail,wail,and main.The word film,on the other hand,clearly lives in the country with few neighbors(only firm and fill).Serial search models would predict that large neighborhoods would increase access time because more entries would have to be perused before word recognition could take place.Parallel search models,however,would predict that spreading activation from numerous neighbors would facilitate eventual recognition of the target.Researchers consider faster recognition times for“city”words with many neighbors support for parallel search models.

Connectionist models,one form of the direct-access theories,provide the best explanation for semantic priming effects.The serial search model may prove too cumbersome for the efficiency with which lexical access is accomplished.However,some researchers argue that it may better account for some findings than direct-access models(see Forster,1990,for a review).And neither serial nor parallel processing models are particularly adept at explaining the ability to pronounce nonwords,whose pronunciation cannot be in our dictionaries(see Henderson,1982).As with word primitives,it could be that the task demands of an experiment greatly influence which predictions of serial versus parallel search models are supported.Both types of models provide numerous pathways to access words based on their frequency,grammatical class,phonology,and so on.