-

1.1前 言

-

1.2序

-

1.3目录

-

1.4Part One Foreign Language Teaching Approaches:A Hi...

-

1.4.1Chapter 1 Traditionalism

-

1.4.1.11.0 lntroduction

-

1.4.1.1.11.0.1 The Grammar-Translation Method

-

1.4.1.1.21.0.2 The Cognitive Theory

-

1.4.1.21.1 The buddingof the G-T Method

-

1.4.1.31.2 Early application of the G-T Method

-

1.4.1.41.3 Development of the G-T Method

-

1.4.1.51.4 Summary

-

1.4.2Chapter 2 Modernism

-

1.4.2.12.0 lntroduction

-

1.4.2.22.1 Various methods

-

1.4.2.2.12.1.1 The Direct Method or approaches

-

1.4.2.2.22.1.2 The Audio-Lingual Method

-

1.4.2.2.32.1.3 The Audio-Visual Method

-

1.4.2.2.42.1.4 The Communicative Language Teaching Approach

-

1.4.2.32.2 Summary

-

1.5Part Two Foreign Language Teaching Approaches:Theo...

-

1.5.1Chapter 3 Foreign Language Teaching And lts Adjace...

-

1.5.1.13.0 lntroduction

-

1.5.1.23.1 Foreign language teaching and linguistics

-

1.5.1.2.13.1.1 Linguistics in foreign language teaching

-

1.5.1.2.23.1.2 Beginnings of modern linguistics

-

1.5.1.2.33.1.3 Characterization of linguistics today

-

1.5.1.2.43.1.4 The view of language in modern linguistics

-

1.5.1.2.53.1.5 Contributions of linguistics to foreign lang...

-

1.5.1.33.2 FLT and psychology

-

1.5.1.3.13.2.1 lntroduction

-

1.5.1.3.23.2.2 The historical background of psychology and ...

-

1.5.1.43.3 Summary

-

1.5.2Chapter 4 Linguistics:Structuralism vs Generativis...

-

1.5.2.14.0 lntroduction

-

1.5.2.24.1 Structuralism

-

1.5.2.34.2 Structuralist grammar and FLT

-

1.5.2.3.14.2.1 Content

-

1.5.2.3.24.2.2 Form

-

1.5.2.3.34.2.3 The most striking gaps in structuralist gram...

-

1.5.2.44.3 T-G grammar vs structuralism

-

1.5.2.4.14.3.1 Transformational-Generative grammar and FLT

-

1.5.2.4.24.3.2 Structuralism

-

1.5.2.54.4 Summary

-

1.5.3Chapter 5 Psychology:Behaviorism vs Mentalism

-

1.5.3.15.0 lntroduction

-

1.5.3.25.1 Associationism

-

1.5.3.35.2 Behaviorism and FLL

-

1.5.3.3.15.2.1 Behaviorism and language acquisition

-

1.5.3.3.25.2.2 Behaviorism and FLT

-

1.5.3.45.3 Mentalism vs behaviorism

-

1.5.3.4.15.3.1 Mentalism

-

1.5.3.4.25.3.2 Mentalism in language teaching

-

1.5.3.4.35.3.3 Behaviorism

-

1.5.3.55.4 Summary

-

1.6Part Three Mother Tongue Interference And Foreign ...

-

1.6.1Chapter 6 Positive Role of Mother Tongue as a Lear...

-

1.6.1.16.0 lntroduction

-

1.6.1.1.16.0.1 Attitudes towards errors

-

1.6.1.1.26.0.2 Error taken as a part of language creativity

-

1.6.1.1.36.0.3 The significance of learnerserrors

-

1.6.1.26.1 Behaviorist approaches to MTl

-

1.6.1.2.16.1.1 Contrastive analysis hypothesis

-

1.6.1.2.26.1.2 Criticism on CAH

-

1.6.1.2.36.1.3 CAH and behaviorism

-

1.6.1.36.2 MTl as a learner strategy

-

1.6.1.3.16.2.1 lnterlanguage theory

-

1.6.1.3.26.2.2 Errors from overgeneralization

-

1.6.1.3.36.2.3 Stages of interlanguage development

-

1.6.1.3.46.2.4 Empirical evidence of variation in interlang...

-

1.6.1.46.3 Summary

-

1.6.2Chapter 7 Bilingual Mental Lexicon And lts lmplica...

-

1.6.2.17.0 lntroduction

-

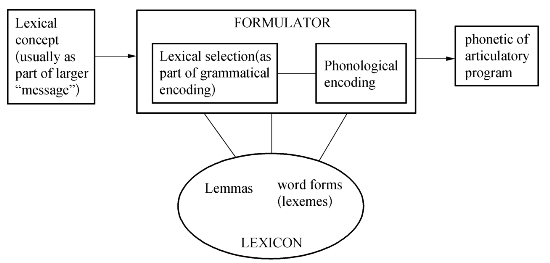

1.6.2.1.17.0.1 Lexical access in speech production

-

1.6.2.1.27.0.2 Models of lexical access

-

1.6.2.1.37.0.3 Representation of meaning

-

1.6.2.1.47.0.4 Models of semantic representation

-

1.6.2.27.1 Mental representation of bilingual lexicon

-

1.6.2.37.2 Models for bilingual lexical memory

-

1.6.2.3.17.2.1 The balanced theory

-

1.6.2.3.27.2.2 The iceberg analogy

-

1.6.2.3.37.2.3 Concept-mediation vs word-association

-

1.6.2.47.3 Summary

-

1.7Part Four Conclusions:ACritique of the Grammar-Tra...

-

1.7.1Conclusions

-

1.7.2List of Reference Books

-

1.7.3List of Abbreviations

-

1.8后 记

1

语法—翻译教学法面面观