6.2.4 Empirical evidence of variation in interlanguage

(1)Causes of systematic variation

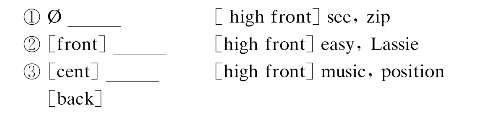

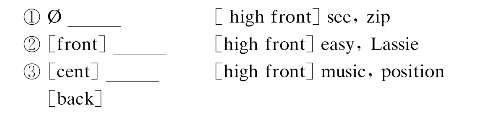

Several theories(like the Labovian and‘function-form’models)assume that linguistic context affects variation in IL forms though no single theory of IL variation is based entirely upon this factor.Some variables(linguistic structures which have more than one variant realizing them),whether phonological morphological or syntactic,can be shown to vary in form depending upon those linguistic forms immediately adjacent.Some environments seem to have a‘facilitating’effect,correlating highly with an increased number of target-like variants;other environments seem to be‘debilitating’,correlating with an increased number of nontarget-like variants.L.Dickerson(1974)W.Dickerson(1976)and Dickerson and Dickerson(1977)were the first to document this cause of IL variation.Dickerson(1974)examined the pronunciation patterns of ten Japanese learners of ESL.Each subject was assessed three times over a nine-month period,by means of a test consisting of three tasks:free speech(with varying topics),the reading of dialogues,and the reading of word lists.The learners'productions were transcribed phonetically and their pronunciation of four variables-Z.H.R and L-was examined.The learners'pronunciation was analyzed in terms of both contextual variation(the influence of phonological environment on the phonological variants of these four variables)over time and situational environment(the influence of task type)over time.The accuracy of the variants was related to phonological environment.For example,the large variant of R occurred most frequently immediately before a mid vowel,and less frequently before a high vowel.As another example,the following three environments are listed in an order favoring suppliance of alveolar sibilants(context 1 favors suppliance most and context 3 the least):

A careful analysis of all the variants supplied for the four variables over time supported some,but not all,of Dickerson's original hypotheses,which were based upon Labov's notion of‘staging’as a process of language change;the learner initiates change in one linguistic environment,then moves to the next,and the next through time.Dickerson's basic hypothesis was upheld:learners ordered and maintained the order of environments,and moved toward the target norm by means of variant staging within each environment.However,Dickerson began with the same assumption Labov had:that the second-language learner begins with invariant environments—for example,invariably substituting a native-language variant in all environments,however,her results showed that learners could begin with variation in any or all linguistic environments.So,a secondlanguage learner could begin the learning process already capable of producing the correct target variant in some or all environments,or with an ability to variably approximate that form in some or all environments.The assumption of a categorical point of origin for each environment appears to be untenable for the language learner,as opposed to a speech community.

More evidence on the role of linguistic environment in the‘staging’process in second-language acquisition comes from studies on variation in the syntactic and morphological forms of interlanguage.Shortly after the Dickerson research on the effect of linguistic environment on IL phonology was published,Hyltenstam(1977,1978)published his research on the effect of linguistic environment on interlanguage syntactic variables.Hyltenstam(1977)studied the acquisition of negation by adult learners of Swedish as a second language.He was able to show that these learners'placement of the negator systematically varied depending on whether the clause it occurred in was main or subordinate,and whether the finite verb was auxiliary or lexical.Similarly,Hyltenstam(1978)showed that subject-verb inversion in the ILs of adults learning Swedish as a second language was dependent upon linguistic context.In‘yes-no questions’,inversion was much more frequent when the finite verb was an auxiliary than when the finite verb was a lexical verb.

Ellis(forthcoming)also sets about identifying and ordering the linguistic environments which influence the production of some morphological forms,and argues for a theory that can explain contextual variation in IL.The study is a longitudinal one of three children(one Portuguese,two Pakistani)acquiring English as a second language.The children were interviewed over a two-year period,at weekly intervals during their first year and biweekly intervals during their second year.Two forms were selected for study:third person singular-s.a categorical targetlanguage rule,and copula-s,a variable target-language rule.For third-person-s,it was found that-s was supplied on the verb most frequently when the subject was a pronoun rather than a noun.For copula-s,contracted's was most commonly produced when the preceding element was a personal pronoun;full or zero copula occurred more when the preceding element was a noun phrase.Within pronoun contexts,an order of favorability could be established,such that That/It/What were more favorable for contraction than He/She,which in turn were more favorable than There/Here/Where,in turn more favorable than This.

It can be concluded that the discussion of the effect of linguistic context upon IL variation with Meisel et al.'s(1981)caution that learners differ from one another in the route which they follow in second-language acquisition—a caution which researchers interested in phenomena like‘staging’would do well to keep in mind:

One cannot conclude that a given rule will first be applied in one specific context,then for the next(possibly the more complex one),and so on.Learners differ greatly with respect to which context is most suitable for the application of a new rule(Meisel et al 1981:126).

(2)The influence of the interlocutor,topic and social norms on the variability of interlanguage

Advocates of these social psychological theories argue,like Bell(1984),that a psychological process like‘attention’can never be viewed as a cause of style-shifting—since something must in turn cause that attention to be focused on language form.We must look for alternative causes to social factors,it is argued—factors which,unlike‘attention’,can be empirically observed.

In this part,the empirical evidence documenting the influence of the following constraints on IL variation:the interlocutor,the topic of discourse,and the social normsactivated in the communicative situation will be shown.It will become clear that there are surprisingly few studies on these factors—and almost no studies establishing clear relationships between particular linguistic features of the IL and these social constraints.

Several studies supply empirical evidence showing that the identity of the interlocutor is systematically related to variation in interlanguage production.Ervin-Tripp(1968)studied the English produced by Japanese women who were speaking to a Caucasian American and a Japanese interviewer.She found that the responses to the Caucasian American were shorter,with more disrupted syntax,and contained more transfer from Japanese vocabulary.

Analysis at the discourse level will be made showing a strong interlocutor effect on IL variation.In elaborating her model of situational variability,Cathcart studied eight bilingual Spanishspeaking children learning English in a bilingual classroom in California.Speech data were gathered as the children interacted with one another and with adults in a variety of formal and informal classroom and research situations.The data were coded for language functions and their linguistic realizations;longitudinal change and individual differences were noted.Cathcart was able to identify four major situational constraints that influenced her subjects'language behavior:interlocutors,conversational control,task stage,and task type.The author of the present study here will examine her findings with regard to the influence of the first two constraints,both of which appear to be directly related to the interlocutor.

The age and authority relationships of the subject's interlocutors influenced the relative frequency of control behavior and information-sharing behavior.So,for example,if the interlocutor was an adult,there was more information-sharing(announcing,requesting,expressing),whereas if the interlocutor was a child,there were more control acts(initiating,supporting,responding).Most of the children's language addressed to adults in a playhouse or seatwork situation,for example,consisted of requests for information.Indirect requests were addressed,not to children,but almost exclusively to adults during assigned tasks.

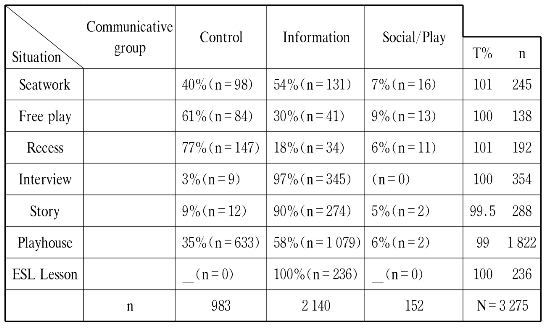

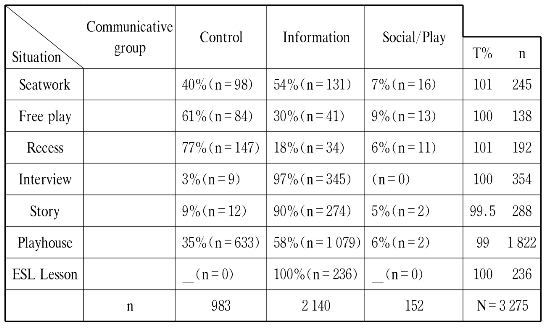

A second situational constraint postulated by Cathcart is conversational control.This constraint relates to the social power of the interlocutor as opposed to that of the speaker's.In certain situations,for example,the teacher normally has control over rules for speaking;in others,the norm is for student control.A summary of the language functions used in the seven situations examined in Cathcart(1983)is displayed in Table 6.4.

In this study,in situations where the learners were not in control,their language consisted of words and short phrases with formulaic chunks.In situations where they were in control,there was a wide variety of communicative acts and syntactic structures.In‘adult-controlled situations’,as in ESL classes,there were more‘information-sharing acts'(e.g.‘Guess what?’,‘That's a cowboy’,‘You're ugly’),while in‘child-controlled situations’,such as recess,children produced more‘control acts’(e.g.‘Heylookit’,Gimme that',‘Come here’).It should be pointed out that the evidence of variation at the discourse level described by Cathcart does not seem to fit easily into the SAT framework of convergence/divergence.

Table 6.4 Percentage of language falling into each of four communicative act groups.Cathcart(1983)

The influence of the interlocutor upon IL variation which is shown at the phonological level seems more amenable to an SAT interpretation.Beebe(1977a,b)reports on a study on the codeswitching behavior of 140 Chinese-Thai bilinguals in response to systematic manipulation of the identity of the interviewer.Beebe(1977a)reports on the behavior of 17 of these bilinguals,all Chinese teachers in Bangkok and all fluent in both Chinese and Thai.Each teacher was interviewed twice,by a Chinese interviewer(with no Chinese social dialect in Thai)and by a Thai interviewer.The same topics were introduced in the same order by each interviewer.Records were kept of the incidence of nine phonological variables in the bilingual teachers'speech in response to each interviewer.It was found that these bilinguals used more Thai variants than Chinese when they were speaking to the Thai listener,and more Chinese variants than Thai when speaking to the Chinese listener.In terms of Speech Accommodation theory(Beebe,L 1977b),these shifts are viewed as evidence of convergence of the speaker toward the interlocutor.Beebe found that 61 Chinese-Thai children responded to the ethnicity of the interviewer in the same manner.Beebe(1977b)says that the upper-middle-class children in this study shifted significantly more than lower-middle-class children.

The influence of the interlocutor on IL variation is evident even at the acoustic level.Flege(1987)provides very specific and interesting evidence of the influence of interlocutor on the pronunciation of L2 sounds—and native language sounds—by second-language learners.He made acoustic measurements of voice onset time and vowel formants in words spoken by adult native speakers of English and French who were learning(respectively)French and English as second languages,and compared these measurements to those produced by monolingual English and French speakers.He found that the advanced L2 learners'production of‘similar’sounds in the target language and the native language seemed to converge.That is,their production of for example,/t/in the TL became more NL-like and at the same time their production of/t/in their ML became more TLlike.Flege notes that when he elicited data from two monolingual French speakers in his‘obviously English-accented French’,their productions of/1/in French became more English-like—a phenomenon he attributes to‘the tendency of talkers to adapt their speech to that of an interlocutor’.Here again,Speech Accommodation theorists would consider this as evidence of convergence at the acoustic level.

There are,of course,other studies on the effect of the interlocutor on interlanguage production;for example,Young(1987)argues that higher proficiency learner's use of noun plural-s was most strongly influenced by the amount of social convergence between the learner and the interlocutor.

In our discussion,we have seen some evidence that indicates that learners style-shift in such a way as to accommodate their interlocutors in their use of interlanguage—a phenomenon which Speech Accommodationists would call convergence.In contrast,Rampton(1987)cites anecdotal evidence based on his observation of Pakistani children in an English class in Britain,which illustrates the process of divergence.He observed that these children,who had two variants of a negative form:‘I don't+verb’and‘Me no+verb’,actually used were of the nonstandard‘Me no’variant when addressing their English teacher...a circumstance in which the‘attention to speech’approach might predict increase in use of the opposite variant.Rampton hypothesized that the Pakistani children were using the‘Pakistani English’variant‘Me no’in order to stress their solidarity with the Pakistani ethnic group over against the ethnic group of the English teacher,and so selected the variant which would cause their speech to diverge from that of the English teacher.Woken et at(1987)present evidence showing that when the second-language learner has greater expertise in the field being discussed than does a native-speaking interlocutor,the learner uses far more directives than in other situations and speaks more than does the native speaker,thereby in some sense diverging from the interlocutor.

A few studies have attempted to establish or measure more directly the perception of the learner with regard to his/her attitudes towards their interlocutors in specific speech situations,and the way in which these affect their style-shifting in interlanguage.For example,Gatbonton(1978),in a study of English learners of French,found that these learners stated that they felt more confident when speaking in the formal style of the IL than the casual,and attributed more negative characteristics to themselves and to their interlocutor in casual speech situations.

To summarize the empirical evidence on the influence of the interlocutor on IL variability,we can make two observations:first,there does seem to be clear evidence that second-language learners produce different variants in response to different interlocutors;but,second,there are surprisingly few studies documenting this effect.There are a number of interesting hypotheses that could be explored by further research,but clearly more data are needed.

Even less evidence is available establishing the influence of topic on IL variation.The Aono and Hillis study involved a topic shift,although the specific effects of this shift are not explored.Although it is generally agreed that topics which generate emotion on the part of the speaker will induce style-shifting of some sort,controlled studies are,in general,not available to establish what features,exactly,shift in response to such topics.Lantolf el al.(1983),the topic shifted to one in which he was heavily invested.Beebe(1983)cites a study by Bourhis and Giles(1977),in which native English-speaking Welsh subjects in Wales who were learning Welsh as a second language(Lantolf,1987)show that an adult learner of FSL style-shifted significantly when were interviewed in English by an RP-speaker.After being asked an initial neutral question,they were asked an ethnically threatening question(intimating that Welsh should no longer be spoken).Those learners with a strong integrative motivation for learning Welsh responded to this topic with a stronger Welsh accent in their English.Those with an instrumental motivation for learning Welsh decreased their Welsh accents in response to the topic.Woken et al.(1987)show that when the topic is one in which the learner has more expertise than the native-speaking interlocutor does,the learner tends to dominate the flow of talk,using more directives and responding to the interlocutor's increased appeals for help with,for example,vocabulary.Eisenstein and Starbuch(1987)report on a follow-up study to Lantolf's,assessing the effect of the learner's investment in topic on learner accuracy with the verb system,use of self-correction and repetition.

Finally,the empirical evidence available documenting the influence on IL variation of social norms activated in the communicative situation will be examined.

A number of studies do provide some evidence that social norms influence learners'interlanguage.Dubois et al.(1981),in their study of negation in French L2,concluded that the degree of variability in their subjects'interlanguage depended in part on the learner's position regarding certain social norms.Meisel et al.(1981)have shown that individual learners with different social norms may pursue very different routes in their acquisition of German as a second language.The non-integrative orientation of some learners may cause them to use strategies like restrictive simplification that resurfaces at several stages of development,resulting,for example,in deletion of the copula for these learners.

Social norms may be inherent in the general attitude of the learner,as above,but they may also vary from communicative situation to situation.Clearly,for example,the Aono and Hillis(1979)study shows that Aono had internalized strong social norms about the importance of maintaining a certain image in conversations with professors.Littlewood's(1981)posited‘pedagogical norm’seems in operation here.Littlewood himself cites Schumann's(1975)study:before instruction,his subject Alberto produced 22 percent of his negative forms correctly in spontaneous speech and 10 per cent correctly in a test situation.After instruction,the figure for spontaneous speech was little changed(20 per cent),but that for the test situation rose to 64 per cent.Thus,his newly acquired pedagogic norms were affecting his performance greatly,but only in certain kinds of situation.

It has been seen in the work of Beebe(1980),Schmidt(1977)that learners may bring certain social norms relevant to the use of their native language to their use of the interlanguage,transferring prestige variants from their native language into their interlanguage in formal speaking situations.

Thus,social norms—both those residing in relatively permanent attitudes of the learner towards the target language,and those relating to specific social situations—may influence variation in IL.