6.2.3 Stages of interlanguage development

(1)contribution of the developmental studies

One contribution of the developmental studies was the identification of strategies employed by SL learners.Huang(1970)studied the acquisition of English by Paul,a five-year-old Taiwanese boy.Huang found that his subject used formulaic utterances such as‘See you tomorrow’in appropriate situations.The other strategy Paul employed was to juxtapose two words with a juncture between them to create an English sentence,such as“This...kite”.Thus,Paul formed a rule perfectly consistent with his topic-comment native language.Butterworth(1972)was one of the earliest language acquisition researchers who studied the acquisition of English by an adolescent.in this case a thirteenyear-old native speaker of Spanish.Ricardo,Butterworth's subject,tended to reduce English structure to simple syntax.He also used the strategy of relexificanon,replacing Spanish words with English words while retaining the Spanish syntactic patterns.Hakuta(1974)studied the acquisition of English by a five-year-old Japanese Speaker for a one-year period.Hakuta found that,like Paul,the subject,Uguisu,used formulaic utterances,which Hakuta labelled prefabricated routines.Uguisu,however,also used prefabricated patterns in which at least one slot would be filled by other words with the same part of speech.For instance,Uguisu produced the following:

①Do you saw this rabbit run away!

②Do you bought this too?

③Do you put it?

It is clear that studying the developmental sequences of SL learners can yield important insights into SLA process.This type of study has met with criticism,when researchers maintain an exclusive TL perspective.In 1976,Adjemian cautioned that if it is true that an IL is different from both the L1 and L2,then it must be the product of a unique set of linguistic rules and should be studied as a fully functioning language in its own right,not as an incomplete version of the TL.As Corder(1983)put it,it is only from the TL perspective that we can say that simplification is a language-learning strategy,because how can learners be said to be simplifying that which they do not already possess?

(2)Developmental sequence:interrogatives

All learners seem to pass,regardless of age,native language or(formal or informal)learning context.The sequences consist of ordered series of IL structures,approximations to a target construction,each reflecting an underlying stage of development.To qualify as a‘stage’and to constitute an interesting theoretical claim,however,each potential stage must be ordered(with respect to other stages in a sequence)and obligatory,i.e.unavoidable by the learner(Meisel,Clahsen and Pienemann 1981;Johnston 1985).One of the first developmental sequences to be identified was that for ESL questions.Following initial work by Huang,Butterworth(1972),Raven(1970),Young(1974),researchers in the famous Harvard Project(Cazden,Cancino,Rosansky and Schumann 1975)studied six Spanish speakers,two children,two adolescents and two adults,learning English,naturalistically in the Boston area—over a ten-month period,collecting data through tape-recorded biweekly conversations between the researchers and individual subjects.Table 6.2 will show the developmental sequence for interrogatives in ESL.

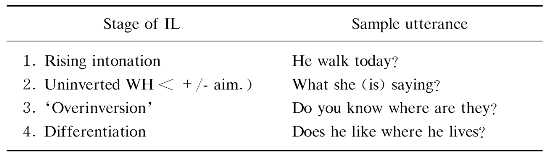

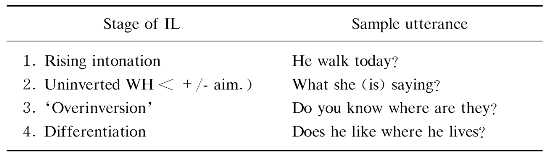

Table 6.2 Developmental Sequence for Interrogatives in ESL

At Stage 1,questions are formed by marking statements with rising intonation.WH-questions appear at Stage 2,but without subject-verb inversion,indeed often without an auxiliary verb at all,e.g.‘Where you go?’and‘Why the Mary not here?’When inversion does enter the system at Stage 3,it is with a vengeance.It is applied correctly to yes/no and WH-questions such as‘Can you speak Japanese?’‘Is he your teacher?’and‘How can you say it?’,first with the modal can and then the copula be,but also overgeneralized to embedded questions,as in‘Do you know what time is it?’and‘I know where are you going.’Finally,at Stage 4,the learner reaches the full target system,differentiating between simple and embedded WH-questions,inverting in the former only.

Most subjects in the studies cited were native speakers of Spanish,which clearly limits the generalizability of any claims made.On the other hand,Huang's subject,Paul,a five-year-old Taiwanese boy,showed the same general pattern,as did Ravem's two Norwegian children,Reidun and Rune,aged six and three.The Norwegian ESL data did suggest some influence for the learners'L1 on the sequence,the children producing relatively few intonation questions in the subset of yes/no questions formed with copula,such as‘Are you hungry?’In those cases,they are usually inverted,as required,Raveni points out,in copula yes/no questions in Norwegian.Where WH-questions were concerned,however,Norwegian would predict utterances like‘Where go Mary?’but the children instead produced uninverted WHquestions at Stage 2,like‘Where Mary go?’,following what seems to be the ESL IL norm for interrogatives.

(3)Developmental sequence:negation

Brown and his associates,who studied the acquisition of these structures by children examining the acquisition English as an L1 Milon(1974)confirmed Ravern's findings.Examining the acquisition of negation in a study of a seven-year-old Japanese speaker learning ESL,Milon reported that his subject produced negative utterances that were very much like those of children acquiring English as a native language.Likewise.Dato(1970),studying the acquisition of Spanish by SL learners who spoke English natively,discovered that SL learners follow a pattern of verb phrase development in Spanish similar to that of native Spanish speakers.Such claims of similarity between L1 and L2 developmental sequences met with opposition,however.Wode(1976),studied the ESL acquisition of four German-speaking children aged four to ten.Wode showed disagreement with the claims of the equivalence between the L1 and L2 developmental sequences.Instead,he argued that there were differences,that the differences were systematic and that they were due to the children's relying on their L1 only under a structural condition where there was a‘crucial similarity’.For example,Wode's subjects exhibited a stage in their acquisition of the English negative in which the negative was placed after the verb:

①John go not to the school.

Such statements appear to be the result of negative transfer from German.While this is no doubt true,it is not the case that English disallows post-verbal negation.In English the verb be and auxiliary verbs are followed by the negative particle:

②He isn't listening.

③She can't mean that.

Thus,Wode argued,the language-transfer error arose since negative placement in English and German were similar enough to encourage the children reliance on their L1.

Another well-known developmental sequence is that for ESL negation(Table 6.3).Learners from a variety of typologically different first language backgrounds have been observed to pass through four major stages:no+X,no/don't V,aux-neg,and analysed don't(for review,see Schumann 1979).Thus,at stages 1 and 2,not just speakers of languages like Spanish,with preverbal negation,but also speakers of languages such as Swedish,Turkish and Japanese,with post-verbal negation,all produce preverbally negated utterances.

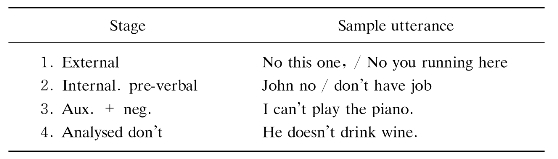

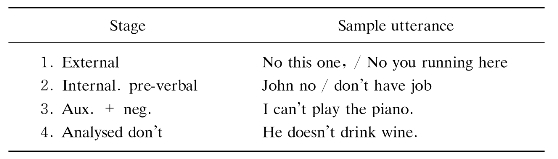

Table 6.3 Developmental Sequence for ESL Negation

At Stage 1,externally negated-constructions like‘No book’,‘No is happy’and‘No you pay it’occur,although they seem rare in adult learners,and particularly ephemeral in speakers of L1s with post-verbal negation.Internal pre-verbally negated strings,on the other hand,like‘He no can play good’,‘They not singing’and‘He don't have car’are very common.No is the typical(often the only)negator at Stage 1,while no,not and don't are all used at Stage 2.Utterances such as‘I don't like Los Angeles’at Stage 2 can temporarily lead a researcher(or teacher)to believe the learner has mastered English negation.A preponderance of utterances at this stage like‘He/she don't like job’,‘John don't come to school(yesterday)’and‘I don't can shoot good’reveals,however,that don't is really being used as an unanalyzed negative particle,not as auxiliary+negator.Stage 3 sees the placement of not,usually in its contracted form,following can in particular,as in‘I can't play’,and the be verb as in“It wasn't so small.”The fact that can't and wasn't are frequent in the input and are often the first to appear,and that most early Stage 3 items use the contracted n't form,suggest that some initial examples,at least,may be unanalyzed chunks.If so,the aux-neg rule soon becomes productive.Perhaps by analysis and generalization from it,the learner then moves to Stage 4,with use of the full target system of aux+neg and analyzed don't.Attainment of the later stages,as Stauble(1981)demonstrated,is related to the development of other VP(verb phrase)morphology.Stage 4,for example,requires control of a full auxiliary system,including the ability to inflect correctly for number and time reference(e.g.isn't,weren't,don't,doesn't and didn't).

In addition to the commonality of the sequence as a whole,a striking feature of the negation findings is the pervasiveness of initial pre-verbal constructions.Although speakers of L1s with pre-verbal negation tend to spend longer at Stages 1 and 2,while learners whose L1s have post-verbal negation may traverse these stages quite quickly.

(4)Development of formulaic utterances

Earlier we cited the work of Huang(1970)and Hakuta(1974),who identified the use of formulaic utterances as one strategy their subjects employed.Fillmore(1976)feels that the memorization of such utterances is indispensable in SLA,for she believes it is the memorized utterances which get analyzed and out of which the creative rules are thus constructed,Krashen and Scarcella(1978)adopt a very different position.They believe that memorized utterances and creative speech are produced in ways that are neurologically different and that,therefore,there can be no interface between them.Schmidt(1983)could find no evolution towards creative rules from his subject's memorized utterances(See also Hanania and Gradman 1977).However,Schmidt's subject,Wes,controlled over a hundred memorized sentences and phrases,and this repertoire considerably enhanced his fluency.For Wes,Schmidt concludes—memorization appeared to be a more successful acquisition strategy than rule formation.

Even if much of Wes's competence in English were due to his having relied on memorized utterances,this would not specifically refute Chomsky's view that language acquisition is a product of rule formation(see Schmidt and Frota 1986 for discussion).As Johnston(1985)reminds us,what Chomsky himself has maintained does not mean that the speaker has applied it each time.‘In fact that grammar rules are not psychologically real.Just because a sentence can be explained by the application of a particular linguistic rule,this,Johnston observes,‘it would seem plausible that a good deal of native speaker linguistic behavior is quite as reutilized as the“formulaic”language of learners.’(p.58)

(5)Development of forms and function

A study is made by Huebner illustrating the value in studying a learner's speech in its own right.Huebner investigated the patterns of‘waduyu’and‘x is a y’(where x and y are slots)in his one-year longitudinal study of a Hmong-speaking adult learning ESL.Not surprisingly,Huebner found that the functions which were assigned to these forms by his subject were not TL functions.Waduyu,for instance,functioned as a general WHquestion marker,as in

①Waduyu kam from?(Where are you from?)

②Waduyu kam Tailaen?(How did you come to Thailand?)

③Waduyu kam?(Why did you come?)

④Waduyu sei?(What did you say?)

Later,other forms appeared to fill some of these roles;for example,the subject used watwei for questions involving means.Finally,waduyu disappeared altogether.Huebner's study,therefore,also calls into question whether in fact learners using prefabricated routines or formulas are really using them appropriately right from the beginning.He suggests that the acquisition of appropriate functions for formulaic utterances may be an evolutionary process.

That the mapping of function on form or form on function is an evolving process is undoubtedly true,not only for formulaic utterances,but for other forms in the language.Wagner(1975)and Wode(1980),for instance,demonstrate that learners do not learn all the functions of a particular form at the same time.Their German-speaking subject used“didn't I”as a past-tense marker for some time before he used it as a negator.They drew a conclusion that‘it is obvious that one cannot generally claim that the function is acquired before the form or that the form is acquired before the function.’(p.92)

Cases such as these,where a structure in a common IL sequence cannot easily be accounted for by reference to either the L1 or the L2,are powerful evidence for those who claim that IL development is guided at least in part by language universals.They are also evidence against a pure restructuring view of IL development,which holds that learners start from the L1 and develop towards the target language by a process of relexification(i.e.use of L2 words in L1 syntactic patterns)and replacement of L1 grammatical features.Conversely,they are consistent with the notion that IL development is a process of gradual‘complexification’,or recreation of the L2 in much the same way that children‘recreate’their mother tongue in first language acquisition.

While little experimental research has been conducted,studies so far suggest that these and other‘natural’IL sequences,e.g.those claimed for German SL word order(Clashen,1980)and for ESL relative clauses are strongly resistant to alteration by instruction and possibly immutable.Modifications due to L1 influence may delay initiation of a sequence,delay or speed up passage through it,or even add substages to it,but never seem to involve either omission of stages or changes in the sequence of stages.As with the so-called‘natural order’for morpheme accuracy,most of the morpho-syntactic developmental sequences identified to date are language-specific,and so lacking in generalizability,and once again,explanations other than rather genera appeals to‘internal learner contributions’are in short supply.