4.2.3 The most striking gaps in structuralist grammars

(1)Structuralist grammars present an incomplete description of the grammatical system of language.In simply providing an inventory of forms and constructions that appear in a necessarily limited corpus,they do not provide the rules needed to construct an infinite range of grammatical sentences.

No one argues that the lists of basic structures provided by any distributional or tagmemic grammar do not constitute good working tools for the beginning of the language learning process through the Audio-Visual or the Audio-Lingual Methods.If,however,one admits that to know a language,i.e.to be able to understand and produce an infinity of utterances,these beginning steps need to be followed by a stage nowadays of ever greater importance,where creative usage of language has to be developed in the pupil,then as Chomsky has clearly shown,structuralist grammar in its inability to account satisfactorily for this creativity is bound to fail.

(2)Structuralist grammars attach excessive weight to grammatical fads of secondary importance(e.g.morphological or morphophonological rules).

An noticeable fact is that in the first structuralist description of French written in 1948,56 pages long,about ten are given over to phonology,thirty or so to morphophonology and morphology and only ten to syntax,whatever the linguistic value and pedagogical importance are.

Language has reflected a behaviorist concept of language learning.Principally under the influence of the psychologist Skinner,this concept underpinned a model of learning concerned with enabling pupils to acquire the necessary automatisms for the practice of spoken language in daily communication.

Both Audio-Visual Methods and courses of structural exercises that have increased greatly in number since the 1940s derive from this coming-together of linguistic and psychological research.Structuralist grammar provided the framework of slots within sentence patterns that could be manipulated by substitution and transformation operations.

(3)In structuralist grammars much more than in traditional grammars,syntactic relations very often receive slight treatment.In descriptions such as Hail's for French,or Hill's for English,what one finds set out in a neat inventory are the principal constructions of the language;nowhere,however,are any indications found of those relationships holding between the constructions which are quite obvious to native-speakers.As an example,one finds:

(a)the active declarative affirmative construction:

The governor refused permission for the demonstration.

(b)the active declarative negative construction:

The governor did not refuse permission for the demonstration.

(c)the active interrogative affirmative construction:

Did the governor refuse permission for the demonstration?

(d)the passive declarative affirmative construction:

This demonstration was refused permission by the governor,etc.

Each of these constructions is presented in isolation without indicating those extremely useful and productive rules for language teaching that allow speakers to shift from one construction to the other.

Similarly,different constructions such as:

(a)I expected it

(b)someone fired the man

(c)the man quit work

are presented,without,however,providing rules for the formulation of a complex construction from the three component propositions,i.e.

(d)I expected the man who quit work to be fired.

What has to be made clear,then,is that structuralist grammars did not provide sufficient information for the pupil to learn how to formulate new constructions,in particular,complexes,nor did they provide the basis for the systematic teaching of writing,any more that traditional grammars had done.

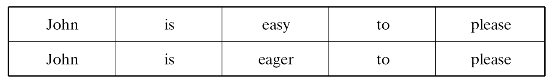

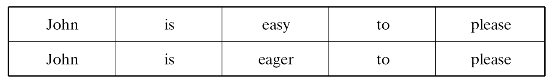

(4)In so far as structuralist grammars only describe the surface structure of sentences,they clearly cannot adequately take account of important grammatical facts.Chomsky's well-known example makes this point:if one defines a grammatical structure as a series of constituents,the two sentences present the same sentence.This runs contrary to native-speaker intuition for whom in the first sentence John is the object of please,(one can say,it is easy to please John),while in the second John is the subject.

If one now takes the noun phrase“The fear of the enemy”

①The fear of the enemy

②The fear of the enemy overthrew our plans

In the sentence,we see a case of syntactic ambiguity which structuralist grammar cannot handle and which becomes clear from the two utterances:

③The enemy was afraid:this overthrew our plans.

④We were afraid of the enemy:this overthrew our plans.

What is necessary,therefore,is to make pupils aware of such grammatical facts because the comprehension of the utterance and often its correct translation into another language(for example,in German die Angst der Feinde and die Angst vor den Feinden)depends on the distinction.Traditional grammar,not relying on a surface structure analysis of such sentences,was well able to distinguish the two constructions;subjective genitive in the first case,objective genitive in the second,and would have gone on to analyze correctly the other examples that have been cited.One is now in a better position to understand Chomsky's affirmation that structuralist grammar represented in certain respects a step backward in the area of the analysis of content and meaning.

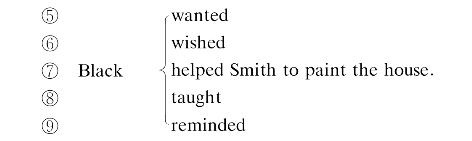

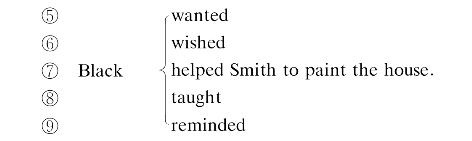

It is worth examining more closely the consequences for language teaching of this omission in structural grammars.R.H.Wagner makes the following point:‘Hence if“patterns”are established solely on the basis of surface structure,it is to be expected that a particular pattern will collapse several deep structures with different interpretations and different transformational potentials.’In analyzing a structure taught by Hornby in his A Guide to Patterns and Usage in English,and presenting it as follows:

Wagner has shown conclusively that such a substitution table mixes together sentences of quite different deep structures,which admit of different transformations in English and have different translation equivalents in other languages.Sentences⑤and⑥only permit the cleft sentence transformation that produces structures of the order:

What Black wanted was for Smith to paint the house.

For sentence⑨it is necessary to add a preposition:

What Black reminded Smith of was to paint a house.

In putting together within the same structural exercise sentences which have such great underlying differences despite their identical surface structure.

(5)Where structuralist grammars generally provide insufficient explanation to guarantee clear comprehension and correct usage,the learner is much more easily led into error.

As Wagner's example above indicates,the presentation of a new structure by means of examples and structural exercises or substitution tables often leaves inexplicit precisely that information which is indispensable for the usage,transformation and translation of the structures in question.In this way such grammars fail to provide the pupil with the means of correctly expressing himself.Laniendella makes the point in his review of Modern English:‘Explanations of grammatical structures in ESL texts are generally insufficient to permit the student to understand what is involved in correct use of a structure’.Only explicit rules of sentence construction can fill that particular gap.

(6)In ignoring notions of degree of grammatically and deviance,structuralist grammar provides an inadequate descriptive instrument for the two areas playing a more and more important role in research into applied linguistics and language teaching:error analysis and stylistic analysis.

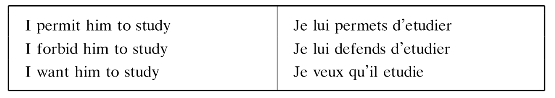

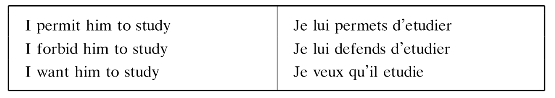

(7)Structuralist grammar does not provide satisfactory bases for two other important areas of applied linguistics in language teaching,contrastive analysis and translation,since in asserting the individual character of each language and in remaining at the surface structure level of utterances,it is prevented to establishing a middle level between the systems of two or more languages.

As Di Pietro once pointed out:Even from the start,the limitations of structural linguistics were evident with regard to CA.The insistence on defining phonological and grammatical categories solely in terms of individual languages made detailed contrastive statements laborious,if not theoretically impossible,to phrase.Only through difficult modification of the theory could the phonemes of one language ever be equated with the phonemes of another,or the morphemes of one be compared to the morphemes of another.In fact,if one accepts with Lado the hypothesis by which one can predict those structures which will cause problems during language learning by comparing the system of the second language with that of the mother tongue of the pupils,one is entitled to doubt seriously whether it would be sufficient for this merely to present in parallel two sets of surface structures from the two languages in question.This was what was done in the first works in the Contrastive Structure Serie and Politzer does the same in the following table:

Nickel and Wagner explain very clearly why this type of contrastive analysis is insufficient for language teaching:‘the results of such comparisons are certainly highly relevant for language tuition but they tend to over-emphasize differences in the surface structures of the languages compared while neglecting more fundamental differences in the underlying deep structures.The following consideration,however,appears to us to be of even greater significance.If one regards speech as a series of processes directed by the rule system in the language(i.e.by its grammar),it follows that interferences occur primarily between the various processes which generate the structure of individual sentences.These processes are in turn dependent on the choices in the rule systems.The conclusion to be drawn from this consideration is that the primary task of contractive analysis must be the comparison of rules and rule systems and not of the structures determined by them.’

(8)Although semantics goes outside the framework of this study,the point should be made that the exclusion of the treatment of meaning by American structuralist linguistics on the grounds that it could not be handled objectively by scientific methods,effectively prevents the provision of necessary information/or the systematic teaching of lexis and more generally of oral and written comprehension.Galisson makes the point that:‘vocabulary is the poor cousin in modern language teaching and has undergone much less of a revolution in teaching than has either grammar or phonetics in the light of modern linguistic research’.

From the views put forward here,it is clear that nowadays there has been a considerable movement away from the enthusiasm which both general and applied linguists showed for structuralist grammar at the beginning of the 1950s.This sudden shift has,however,surprised teachers and placed them in a very uncomfortable situation.Both in the United States and then in Europe they had converted themselves only with considerable difficulty(after a good deal of reticence and a good deal of effort)to structural linguistics,which had been presented to them as a panacea,only now to discover in it considerable numbers of errors.The same is true for methodology where it will be sufficient to point out three major omissions.

(a)The accent placed by early structuralists on formal and distributional criteria at the expense of situational and semantic factors,in addition to the importance accorded by Skinnerian psychologists to a theory of step-by-step learning,led both teachers and pupils to manipulate structures as an end in themselves while neglecting the area of their application in everyday life.Newmark makes the comment that:inspection of language textbooks designed by linguists reveals an increasing emphasis in recent years on structural drills in which pieces of language are isolated from the linguistic and social contexts which make them meaningful and useful to the learner.The more we know about language,the more such drills we have been tempted to make.If one compares,say,the spoken language textbooks devised by linguists during the Second World War with some of the recent textbooks devised by linguists,one is at once struck by the shift of emphasis from connected situational dialogue to disconnected structural exercise.There was thus a great increase in the 1950s and 1960s of boring mechanical drills producing pupils who were often incapable of using these structures correctly in the variety of situations of daily communication.

(b)Structuralists led teachers to think that language was the only variable in language pedagogy and thus to neglect the problems of language learning and teaching.F.C.Johnson makes the comment that,‘if anything,linguists have been too successful for they have seduced us into the belief that language is not only the prime variable in language teaching but virtually the only variable...What it in effect meant for language teaching was that our attention was directed almost exclusively to language at the expense of,and to the neglect of,“teaching”and“learning”.As a result:‘language teaching methodology today is virtually in the state it was 50 years ago when Harold Palmer and others were developing the concept of pattern practice’.Structural linguists were not qualified to put forward a methodology of language teaching,particularly when one realizes that they were interested uniquely in the description of the language code and not in its usage.To the two traditional questions of language teaching:‘What to teach?’and‘How to teach?’,they were able to reply to the first but not at all to the second.As Contreras makes clear:‘Strangely enough however,the main impact of structural linguistics on language teaching has been related to the second question,in the form of the so-called linguistic method’.This method,applied in particular to audio-visual courses and language laboratory exercises,seems today,as a result of its frequently mechanical and oppressive character,to be at odds with teachers'attempts to liberate the creative power of their pupils.‘It is evidently a problem,’Debyser notes,‘that even those methods called“new”or“modern”for the teaching of modern languages risk being considered as ultra-traditional from the point of view of general pedagogy’.Linguists realized their error a little late,as W.Moulton,one of the first protagonists of the linguistic method,points out:‘To judge by what my fellow linguists and I have sometimes said in the past,it might seem as though we thought that we—and we alone—knew all the answers to all the problems of language teaching.We most emphatically do not.In matters of language pedagogy—planning lessons,designing drills,using the laboratory—we know no more than the next man and a good deal less than many.’The one thing which we have to offer is linguistic theory—a rather exciting body of theory on what language is and how it works.This means that when the language teacher wants to know what aspects of language should be drilled,we may have some ideas worth listening to,but when he then asks how these things should be drilled,our ideas are worth no more than anyone else's.

(c)Finally,one is aware today that this new methodology is based on an inadequate model of language learning,i.e.the verbal conditioning theory associated with Skinner.

Chomsky has made this point very clear in his review of Skinner's Verbal Behavior,i.e.that Skinnerian theory does not account in a satisfactory manner for the acquisition and creative use of language.Chomsky recalled these comments in 1964 at a conference of language teaching specialists.‘Within psychology,there are now many who would question the view that the basic principles of learning are well understood.Long accepted principles of association and reinforcement Gestalt principles,the theory of concept formation as it has emerged in modern investigation,all of these have been sharply challenged in theoretical as well as experimental work.It seems that the principles are not merely inadequate but probably misconceived—that they deal with marginal aspects of acquisition of knowledge,and leave the central core of the problem untouched.In particular,it seems impossible to accept the concept according to which linguistic performance is a matter of habit and is acquired slowly by process of reinforcement,association and generalization.’

In conclusion,critics,both in the area of linguistics and methodology,have been severe.As a result,one begins to understand how it is that the most recent manuals and courses of language teaching refer less and less to structuralist grammar.