3.2.2 The historical background of psychology and its roles in FLT

(1)Before World WarⅠ

In the history of psychology,language has always played a certain role,but at no time have linguistic processes been so much in the center of intention as they have been since the fifties and sixties.Psychology which studies the behavior,activities,conduct,and mental processes of human beings.It can be defined as the science of the mental life and behavior of the individual.Speech is one of the features that distinguishes man most clearly from other species,and therefore its function in the life of man is a necessary part of psychological enquiry.Language is only one among many of human behavior studied by psychologists.Over the hundred years of its development as a scientific discipline,psychology has not always paid sufficient attention to speech or language.In the last decades of the nineteenth century,it was more concerned with sense perception.From about 1900,questions of learning,memory,thinking and intelligence(the‘higher mental processes’)were the principal topics of investigation.In the interwar years,the studies of the emotions,personality,psychological growth of the child,and the measurement of individual differences became prominent.Even today one may find psychologists who question whether the psychology of language fruitful field of enquiry.

Around 1900,many of the experiments in psychology,especially studies on memory and mental associations,involved the use of language.Memory experiments,for example,tested the learning and retention of word lists.They indicated that in memorizing the subject tends to arrange and organize the verbal elements to be learnt in some recognizable pattern.Word association experiments,first undertaken by Gallon in 1883 demonstrated that subjects can respond spontaneously and in predictable ways to separate words(verbal‘stimuli’)with words(verbal‘response’or‘reaction’).Such experiments increased not only the psychologists'understanding the human mind,they also suggested principles that govern repertoires in the first language.They are therefore also studies of language behavior.

Around the turn of the century,one of the most exciting approaches to the emotional dynamics of verbal behavior was Freud's treatment of slips of the tongue or the pen.He was able to show these performance errors of speakers or writers had an internal emotional‘logic’,and like dream symbols were clues to stresses and internal conflicts.For this reason,Jung,following Freud,was able to use verbal associations as a diagnostic tool to uncover emotional‘complexes’.The associations,evoked by a given word,although not absolutely predictable,have regularities which suggest that the words in a speech community,as Saussure had also observed,constitute a network of common associative patterns.According to Jung's theory,a person with emotional problems is likely to deviate markedly from the common verbal associations of his speech community.It was observation that suggested to Jung(1918)to treat unusual associations as indicators of emotional peculiarities and stresses,Thus,psychoanalysis and related schools of thought drew attention to the fact that language is not only related to thinking,but also to the affective life of man—an aspect of language which even today is still insufficiently recognized in foreign language teaching.

What interested them particularly in these studies of mental development of the child was the question or how to account for individual differences in development.‘Nature or nurture’was one of the most debated issues.In their explanations of mental growth,psychologists tended to be divided.Some favored chiefly maturational(biological,nativistic)explanations,while others saw mental development as explanations.By the forties,the prolonged debate between nativists and environmentalists had reached a‘biosocial’compromise:the division between the two points of view had become less rigid.Rather than expecting a clear-cut solution,the question was much more one of asking what proportion or what aspects of human functioning could be explained most convincingly as the result of environmental influences and learning.Intelligence was viewed as a good example of a feature in which the‘bio’component was perhaps stronger than the‘social aspect’.In language development,on the other hand,the weight was at the same time considered to be much more on social influences and learning than on biological factors.After all,a child learns the language of its social surroundings.Nevertheless,a basis of neural development was presupposed even among those who interpreted language development almost entirely in environmental terms.

A much debated issue has been aroused concerning the interaction between genetic factors and environmental influences has remained.In the sixties,a fresh controversy on this question was provoked by the claim advanced by Chomsky,Lenneberg,and others,that language development should be viewed as biological rather than as the result of so learning.

Another major issue involving language that has been thought about in psychology for many decades is the interaction between language and other aspects of human psychology.Ever since beginnings of intelligence testing in the early decades of the twentieth century,the growth of language in the child was seen above all as indicator of mental growth.

In answering to the question concerning the relationship between language and thought to be understood?The Swiss psychologist Piaget,in his first major work on language and thought in childhood(1923),advanced the thesis that childhood reflect the mental development of the child.The functional use of language in childhood reflect the mental development of the child.Increasingly however,influenced by the Whorfian Hypothesis,language was seen to have a formative influence on perception and cognition.

On the whole,then,by the middle of the twentieth century,for some psychologists,the rule of language was viewed as a central factor in determining the cognitive and affective states of the individual.Through verbalizations,a decisive influence could indirectly be exercised on the way humans think,feel,and regulate their lives.Not all psychologists shared this central view of language.Some were less convinced of such a direct effect of language upon the mental make-up of the individual.They believed that there was a certain parallelism between language growth and mental growth generally,but this was by no means perfect.Others again believed that a cause-and-effect relationship worked in the opposite direction;they regarded language as dependent upon and a part of cognitive development,

With the development of psychology in the interwar years,and particularly with the growth of educational psychology,several studies attempted to apply the new psychology to foreign language teaching.During that period,the application of psychological thought and research techniques made much more rapid strides than the application of linguistic concepts.In a first critical work on the psychology of foreign language teaching,based on educational psychology.Huse(1931:164-5)viewed the task of language learning rather narrowly as‘essentially a memory problem;it is the learning for recognition or recall.’Huse made a plea for a more experimental approach to problems of foreign language study.In his view,educational psychologists could hardly find‘a more promising field of experimentation and educational measurement.’(1931:7)

The place of psychology in language teaching in Britain in the thirties can be illustrated by a remarkable article(Findlay,1932)which appeared in the newly established British Journal of Educational Psychology.Findlay's article offers in effect an entire theory of foreign language teaching,which besides interesting psychological insights,contains linguistic as well as pedagogical observations.In his psychology,Findlay recognizes more clearly than most observers of his time,and indeed of later periods,the learner's emotional resistance to abandoning the first language frame of reference and his refusal to‘grasp the foreigner's mind by entering into his mode of thought’(op.cit:319).In Findlay's if a language learning is psychologically an imitative task in which the learner‘has to copy the behavior of the native by conscious attention,practicing again and again,establishing a multitude of new habits,all of them contrary to the stream of his own vernacular habits’(op.cit.:32)Findlay is not against memorization because it is important for the learner to establish a‘subconscious store’;for habit is‘unconscious memory’(op.cit.:329).The new habit system,Findlay argues,is best established by grasping it‘apart from our vernacular’.He thus makes plea for an approach to language learning that establishes a form of coordinate bilingualism.‘All the investigations,alike of psychologists and physiologists during the last half-century,confirm the view that the establishment of a separate center of function for every new language is the immediate purpose which the learner must achieve.’(op.cit.:322)

(2)The post-war years:turning to psychology for answers

A new attempt to relate British psychological thought with systematic language learning was made by Stott(1946)in a small book on language teaching in the post-war era.Stott attempts to show that psychological theory is‘capable of improving practice!’(1946:24)The language teaching theory he develops rejects the purely mechanical approach.Stott develops a largely cognitive and active approach:(a)the learner is encouraged to think for himself about the language;(b)he is guided to make linguistic observations;and(c)he is given the opportunity to participate actively language games.Stott,like Findlay,accepts the need for memorization and habituation in language learning,but he derives from the psychology of learning certain principles of learning how to learn.In a tentative way,Stott also makes observations on language and thought and on first language acquisition.The role of psychology,however,remains purely supportive.It serves as a resource for the language teacher and thus provides concepts,ideas,and parallels;but no attempt is made at this stage to develop a coherent psychology of second language learning in its own right,based a the experiences of second language learners.

The question of the optimal age for second language learning was a psychological issue that began to be discussed in the fifties was.The ability of young children to learn languages‘easily’had,from time to time,been noted in the psychological literature(for example,Tomb,1925).But in the fifties it was the view of Penneld,a neurophysiologist at McGill University in Montreal,which aroused widespread attention.Penneld,partly on the basis of his scientific work as a neurosurgeon and partly on his personal conviction,proposed the idea that the early years before puberty offered a biologically favorable stage for second language learning,and he recommended that the early years of childhood should be used more intensively for language training.This viewpoint shared by a growing number of teachers,specialists,and the general public,manifested itself in the introduction of language teaching in the early years of schooling in several countries.The debate on this controversial issue has gone on ever since,and in spite of experimentation,some research,and endless theoretical argumentation,the issue of the optimal age has remained unresolved even thirty years after Penfield's challenge had opened up the debate.

The need for more systematic psychological research on language learning was fully recognized and clearly expressed by Carroll in the fifties:‘we are fundamentally ignorant of the psychology of language learning.’(Carroll,1953;187)Carroll believed that educational psychology might provide helpful answers to pedagogy by carrying out research on specific questions of language learning.

(3)After World WarⅡ

World WarⅡand the post-war era were periods of much interdisciplinary development.Psychologists had become more aware of the fact that the linguistic concepts they had previously used in their investigations were simply common-sense notions of language with which they were familiar as educated persons.They were conscious of the fact that they had not adequately taken into account the more systematic thought on language that had meanwhile been developed by the growing science of linguistics.Linguists,for their part,also wanted to co-ordinate their linguistic studies with those of psychologists.These thoughts led to meetings between linguists and psychologists.The intention of these exchanges was to establish a common basis of discussion on language,to develop a body of common theory,and to study research issues.Such interchanges of ideas which took place in the U.S.A.in the early fifties led to a seminal survey on‘psycholinguistics’,as this new interdisciplinary field began to be called(Osgood&Sebeok,1965),this survey brought together a great deal of information on current thought and research problems.Starting out from Shannon's model of the act of communication a theoretical model defining the role of psycholinguistics in relation to other contributing disciplines was developed.

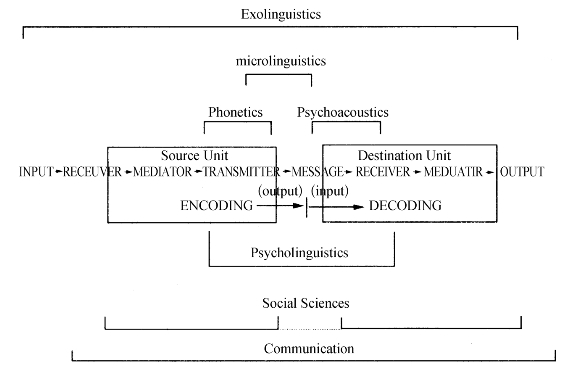

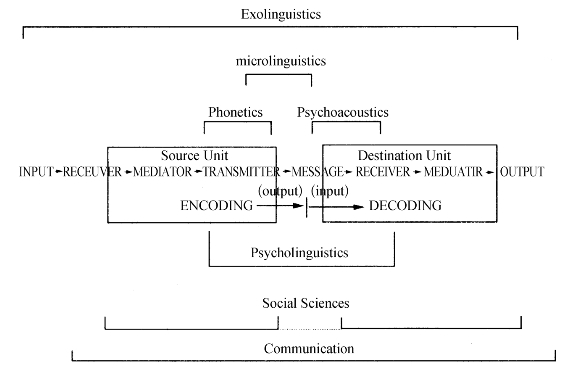

According to Diagram 3.6,the entire field of language study is‘exolinguistics’(more recently referred to as‘macrolinguistics’.Linguistics in the narrower sense(‘microlinguistic’)is given a somewhat wider range than was envisaged by Bloomfield.The place of psycholinguistics was defined in the following terms:‘The rather new discipline coming to be known as psycholinguistics...is concerned in the broadest sense with relations between messages and the characteristics of human individuals who select and interpret them.In a narrower sense,psycholinguistics studies those processes whereby the intentions of speakers are transformed into signals in the culturally accepted code and whereby these signals are transformed into the interpretations of hearers.In other words,psycholinguistics deals directly with the processes of encoding and decoding as they relate states of messages to states of communicators’.

Diagram 3.6 Osgood&Sebeok's representation of the place of psycholinguist among the social and language sciences.Source:(Osgood&Sebeok,1965)

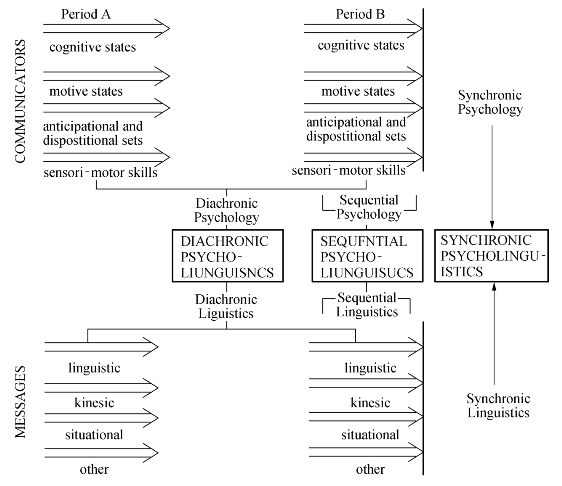

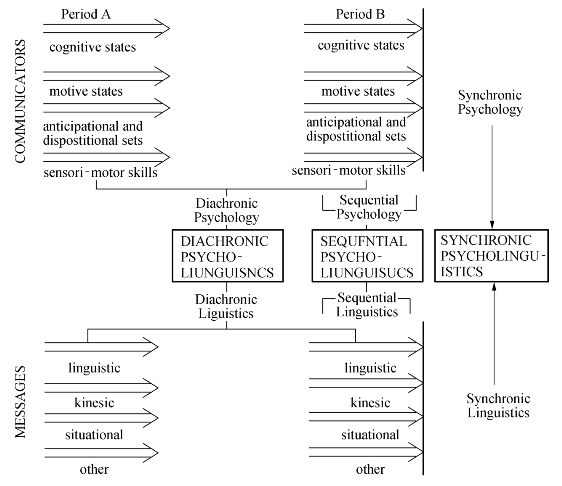

Osgood and Sebeok's representation of the organization of consent in psycholinguistics applied to psychology,which intended to map out the major divisions of psycholinguistics,(Figure 3.7)made it clear that psychology in the top half of the model analyzed persons as‘communicators’,while linguistics in the bottom half studied the communications or messages.Psycholinguistics,then,was the meeting ground between the two.The linguistic analysis was conceived not only as linguistic in the narrow sense but included paralinguistic features of facial and bodily gestures and situations.The psychological analysis of communicators was envisaged comprehensively as directed to cognition,motivation,‘anticipational and dispositional sets’,and sensorimotor skills.The model extended the Saussurian distinction between synchronic and diachronic linguistics to psychology and psycholinguistics.

Figure 3.7 referred to studies of different stages of development and learning in an individual.Diachronic psycholinguistics therefore involves‘comparison between two or more stages in language development’in the individual and in society(op.cit.:126).It includes first language learning,second language learning and bilingualism and the phenomenon of language change.Second language learning and bilingualism were thus given a distinct place in this scheme of psycholinguistics.

Figure 3.7 Osgood&Sebeok's representation of the organization of content in psycholinguistics.Source:(Osgood&Sebeok,1965)

It is evident that in the fifties language was no longer a neglected topic in psychology.Language questions received a new prominence after the publication of Skinner's Verbal Behavior(1957)and the view of this work by Chomsky(1959).The thesis of Skinner's book,an openly radical speculation,developed over a long period and the logical continuation of Watson's behaviorism,was that what is normally called‘language’can be described exhaustively and consistently as‘verbal behavior’.Skinner's argument was that there is no fundamental difference in accounting for fact that a rat in an experimental cage can learn to press a level to receive a food pellet as a‘reward’and the fact that a human can learn to use vocal signals as‘operants’to satisfy his needs.Skinner's thesis accorded with the behaviorist philosophy that provided the commonly accepted ground rules in psycholinguistics of that time;but it was more extreme in that it attempted to dispense entirely with any mentalistic concept.

Chomsky(1959),in a long and famous review article on Verbal Behavior in the journal Language,made a fundamental attack not only on the thesis and the concepts developed by Skinner in this book but,through this review,on the entire behaviorist position in contemporary biology and psycholinguistics.While many psychologists,usually referred to as neo-behaviorists,had for years adopted a less anti-mentalist view of behavior than Skinner,most of them—certainly in North America and Great Britain—had fully accepted the basic principles of behaviorism,particularly in the treatment of language.Carrol(1953)expresses a view that would have found widespread acceptance among psychologists in the fifties:

‘I take the initial position that subjective events can be regarded as behavioral,that they play an important role in many behavior sequences,and...that there are publicly observable indices of subjective events(not the least of which is verbal behavior)and that subjective events may be assumed to follow much the same laws as those events observable as neurological,motor,and glandular responses.’op,cit.:72)

The object of Chomsky's review of Verbal Behavior was to show that the principal concepts of a behaviorist approach to language are totally inadequate to account for language behavior.For example,the concept of‘shaping’and‘reinforcement’which Skinner had transferred from conditioning in animal experiments to language use,was in Chomsky's view completely misleading.‘I have been able to find no support whatsoever for the doctrine of Skinner and others that slow and caret shaping of verbal behavior through differential reinforcement is absolute necessity.’(Chomsky,1959:158)The notion of‘generalization’Chomsky argued,was equally insufficient to account for the creative character of language use:“Talk of‘stimulus generalization’...simply perpetuates the mystery under a new title”(op.cit.:158).Instead of attempting to explain language in terms or the simpler modes of behavior of non-human organisms,psychologists,he said,had better use the evidence of language to reinterpret the characteristic workings of the human mind.A few years later,Chomsky(1966)summarized the criticism of behaviorism in such phrases as these:

(a)“Language is not a‘habit structure’.”(op.cit.:44)“repetition of fixed phrases is a rarity...”(op.cit.:46)

(b)“The notion that linguistic behavior consists of‘responses’‘stimuli’is as much a myth as the idea that it is a matter of habit and generalization.”(loc.cit.)

(c)“Ordinary linguistic behavior characteristically involves innovation,formation of new sentences and new patterns in accordance with rules of great abstractness and intricacy.”(op.cit.:44)

(d)“There are no known principles of association or reinforcement and no known sense of‘generalization’that can begin to account for this characteristic‘creative aspect’of normal language use.”(loc.cit.)

Chomsky had not always made direct psychological claims for his linguistic theory.On the contrary,he often emphasized that a generative grammar and the concept of the native speaker's‘competence’were constructs to account for the linguistic characteristics of a given grammar of a language.They were not to be thought of as models of how a native speaker makes up or interprets utterances.But it was obvious that the notion of competence and the concept of linguistic creativity together with Chomsky's attack on behaviorism would lead psychologists,sooner or later,to re-examine the theoretical bases of psycholinguistics.Moreover,in the course of the sixties,Chomsky himself became more and more convinced that the study of language may very well‘provide a remarkably favorable perspective for the study of human mental processes’(Chomsky,1968:84)so much so that he characterized linguistics as a‘subfield of psychology.’(op.cit:24)Chomsky's work,by the beginning of the sixties,had not only initiated a revolution in linguistics but also in psychology and in psycholinguistics.