-

1.1目录

-

1.2丛书序

-

1.3Forschungskooperationen in der Berufspädagogik– di...

-

1.3.1Jiping Wang Xiao Feng Josef Rützel

-

1.4Research Cooperation in Vocational Education and ...

-

1.4.1Jiping Wang Xiao Feng Josef Rützel

-

1.5Professionalisierung

-

1.5.1Herausforderungen der Lehrerbildung für beruflich...

-

1.5.1.1Birgit Ziegler

-

1.5.2Lehrerkompetenzen und Lehrerhandeln: Modellierungs...

-

1.5.2.1Nicole Naeve-Stoß

-

1.5.2.2Susan Seeber

-

1.5.3Professionalisierung von Lehrkräften für berufsbi...

-

1.5.3.1Philipp Wöll

-

1.5.4Chinese Secondary Vocational School Teachers’ Per...

-

1.5.4.1Tongji Li

-

1.5.4.2Sofie M. M. Loyens Remy M. J. P. Rikers

-

1.5.5Duales Studium in Deutschland— ein verwendbares Mo...

-

1.5.5.1Xiaohui Yang

-

1.5.6Berufspädagogische Professionalität unter veränder...

-

1.5.6.1Uwe Faßhauer Lars Windelband

-

1.6Kompetenzen

-

1.6.1The Subject Specific Didactical Competence of VTE...

-

1.6.1.1Jianping Zheng Tongji Li

-

1.6.2Praxisphasen als Studienelement– Professionalisier...

-

1.6.2.1H.-Hugo Kremer

-

1.6.3Strukturen schulischer Praxisphasen im berufliche...

-

1.6.3.1Silke Lange

-

1.6.4Service Learning als didaktisches Format in der L...

-

1.6.4.1Karl-Heinz Gerholz

-

1.6.5The Sustainable Development of E-Learning: In the ...

-

1.6.5.1Jin Zhao

-

1.6.6Post-Study Pre-Service Practical Training Program...

-

1.6.6.1Jun Li Xianjie Peng

-

1.7Herausforderungen

-

1.7.1The Effect of the Scale, Composition, and Quality ...

-

1.7.1.1Yijun Wang Jin Zhao

-

1.7.2Aktuelle Entwicklungen und neue Zielgruppen in de...

-

1.7.2.1Dietmar Frommberger

-

1.7.2.2M.Ed. Silke Lange

-

1.7.3Lehramtsausbildung für Sozial- und Gesundheitsber...

-

1.7.3.1Marianne Friese

-

1.7.4„Verlierer im Lernen?“ Übergangsproblematiken sow...

-

1.7.4.1Alexander Schnarr

-

1.7.5Curriculum System of Vocational Education in China...

-

1.7.5.1Wenping Zhao

-

1.7.6Internationale Förderklassen an Berufskollegs: Ein...

-

1.7.6.1Petra Frehe

-

1.7.6.2H.-Hugo Kremer

-

1.7.7Evaluation und Bildung: Die deutsche Diskussion zu...

-

1.7.7.1Johannes Karl Schmees

Institute of Vocational and Technical Education, Tongji University, China

Xiujun Qu

Security Office, Tongji University, China

1 Vocational Teacher Training System in China

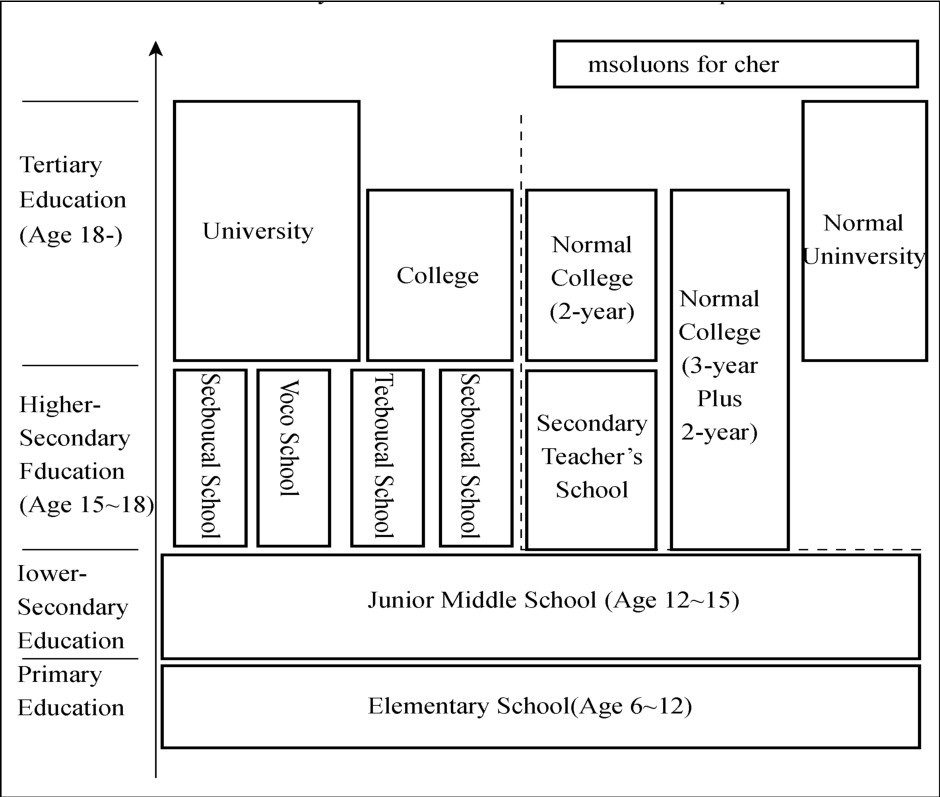

The Chinese formal education system is divided into three levels: primary education, secondary education and tertiary education. As Fig.1 shows, technical and vocational education in China takes place mainly in higher-secondary and tertiary level. Because the compulsory schooling in China is 9 years and includes only the primary and lower-secondary education, attending vocational schools or senior middle schools is not obligatory.

Vocational education traditionally has a lower social status compared to the academic education in China (Xu, 2004). Due to this reason the vocational schools have been regarded as the youths as well as their parents as a second choice or “plan B” when they make education decisions.

However the rapid economic growth in the past decades has led to an increase in the requirements for well-trained, skilled workers. This apparently has positive influences on the vocational education as a whole. On the one hand the school graduates from relatively lower-income families may find attending vocational schooling a good possibility to gain an occupation in a rather short period of time; on the other hand the government has invested remarkable amount of money in the field of vocational education and training.

Fig.1 China’ formal Education System and Institutions for Teacher Preparation

Quite different from vocational education, the teachers traditionally enjoy a rather high social status in China. Despite their modest income levels compared with other professionals of similar education level, teacher as a profession has a good social prestige in contemporary China. The government and legal authority has correspondingly attached great importance to teachers and their preparation. A good example to this is that the teachers law is one of the earliest laws that has been issued in the field of education (1993), two years before the issue of education law (1995).

The central government controls and directs teacher education in general through legislation and regulation, which set the basic preparation requirements and standards of teacher candidates. Under this direction, the local governments, mainly on the provincial level, are responsible for running the teacher education system; they also regulate the concrete entry criteria for teachers (Ding and Sun, 2007).

On the legislative level the requirements for vocational school teachers do not differ from that for the general school teachers on the same level. Basically there are three basic principles under which one can obtain the teaching certificate.

The first one concerns the academic degree the candidate holds. According to the Teachers Law, to obtain qualifications for a teacher in a senior middle school, or a teacher for general knowledge courses and specialised courses in a secondary vocational school, technical school or a vocational high school, one shall be a graduate of a normal college or other colleges or universities with four years’ schooling or upwards, and the corresponding records of formal schooling for the qualifications of instructors who give guidance to students’ fieldwork at secondary vocational schools, technical schools or vocational high schools shall be prescribed by the administrative departments of education under the State Council (Eighth National People’s Congress, 1993).

Since almost all vocational schools are of higher-secondary level or above, this means that a college education is necessary to become a teacher in a vocational school. As Fig.1 demonstrates, there are universities and colleges specifically designed for teacher education.

Originally it is required that only the graduates from these institutions can become teachers. However, due to the lack of teacher supply, the regulations on teacher certification have been loosened since late 1990s, in order to enlarging the teaching force (Ding and Sun, 2007). Professionals who do not have teaching experiences as well as college graduates who do not graduate from the institutions for teacher education can both join the teaching force under certain circumstances.

This relates to the second principle, which requires that those who have not received education and training in teaching should pass four extra tests on pedagogy, education psychology, teaching methods and teaching ability. The first three tests are written exams, whereas in the test for teaching ability the candidate needs to demonstrate his/her ability in subject-matter instruction, classroom management and questioning, etc.

The third principle concerns the language ability, or more specifically, the Mandarin language- the standard Chinese language advocated by the government. A standard system is established by the National Mandarin Test Committee to rank someone’s capabilities of speaking and hearing Mandarin. Theoretically anyone who wants to become a teacher has to reach a certain level in the standard test before having the certificate.

Except the contents described above, neither the teachers law nor the regulation on the qualification of teachers issued by the ministry of education sets other competence or education/training requirements for the qualification of teacher. The provincial governments establish the concrete rules for the implementation of the national laws and regulations mentioned above.

2 Basic Conditions of PTP: Regulations, Infrastructure and Implementations

As mentioned above, the graduates from institutions that carry out teacher education are able to work in the vocational schools directly after college/university if the Chinese language level achieves a certain standard. Even for those college graduates from not-teacher-education institutions can join the teaching force as long as they pass some exams in pedagogy and education psychology etc. This means that officially a “post-study, pre-service” training programs for tvet teachers/students (PTP) does not exist, since they normally start their service and career as a teacher directly after the study program.

However, two sets of programs exist on both the provincial and school level to help the tvet teacher candidates or novice teachers. In this article these two programs are referred to as PTP programs.

The first PTP program is designed for those future teachers during their university/college periods and includes a 10-week internship which takes place in the last year of their study program. This internship is a prerequisite for graduation from college and degree, and is therefore necessary for the service as a teacher. This program is later referred to as PTP1.

The second sets of programs aim for those who already gained their degrees and just started their service in the vocational schools. This sets of programs include a variety of programs during the first two years of their teacher careers. The entire programs are later referred to as PTP2. The PTP2 takes place during the probationary period of the novice teacher which normally lasts for a year. In some schools the PTP2 program is extended for another year after the probationary period is over.

Although the PTP1 and PTP2 took places in different phases of tvet teacher preparation, they actually have a certain degree of consistency. This is reflected in two dimensions: (1) PTP1 is carried out almost at the end of the study program and PTP2 is carried out at the very beginning phase of the teacher service, they are well connected to each other in terms of time; (2) the programs are both designed to introduce the (potential) teachers to the world of work, they are logically coherent in terms of content (more details in the following text).

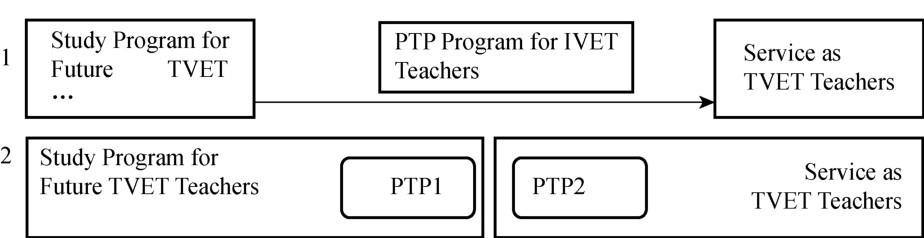

Meanwhile this infrastructure substantially differ from the original (ideal) PTP model, which is clearly divided from both the study program and the service. Thus two different models of PTP can be seen here: one that exists outside the study program and the service period, the other one that is embedded in the existing program of study and service, as Fig.2 illustrates.

Fig.2 Two Models

Both PTP1 and PTP2 have existed in China since decades. However, the PTP1 is much more institutionalised compared to PTP2, the implementation of which is still largely a school business and no clear regulation exist on the national level as to how new entrants to vocational schools shall be trained and introduced to their new job.

PTP1 takes place in both teacher education institutions and vocational schools, and the people involved include university teachers and researchers as well as teachers and personnel in the vocational schools; whereas PTP2 is mainly carried out in the vocational schools.

In the following parts these two PTP programs will be described with greater details.

3 Participants, Curriculum, Teaching, and Graduation

Due to the special character of the PTP programs in China, a different structure is applied here in order to offer a more coherent and comprehensive picture of the programs. In this part the participants of the PTP are briefly introduced, then the basic structure and content of the program is described (including curriculum and teaching), and at the end the graduation requirements are stated.

3.1 PTP1

3.1.1 Participants

The nature of the PTP1 has determined that the participants in PTP1 are college students. For a four-year university, the students are normally at their 7th semester when they start PTP1.

3.1.2 Curriculum and Teaching

Basically PTP1 is a 10-week program consisting of three phases: preparation,internship and summary. The first and last phase (preparation and summary) takes place mainly in the university and each lasts one week. During the 8-week internship the participants shall stay in the vocational schools.

At the preparation phase the participant should get prepared for the internship, make contacts with the internship schools, and make other relevant arrangements.

During the internship each of the participants is assigned an instructor by the school, who is normally an experienced teacher in the corresponding subject. The college where the participants study also assigns a supervisor for him/her, whose task include coordinating with the vocational school, giving advice to the participants, supervising the entire internship and helping finishing the internship report at the end phase of the program. The main tasks for the participants concerns two domains of works in a vocational school, namely teaching and work of class teacher.

In terms of teaching, the participants shall do teaching job at least 4 times (4 teaching hours, 4×45mins), attend the class-teaching of other teachers for at least 20 teaching hours, and deliver the relevant teaching plans, lecture notes, and classroom observation report after the internship. In addition, they should, under the guidance of the instructor, actively take part in other teaching activities in the vocational schools, such as practice and field works of vocational school students, after-school counselling, correction and commenting on homework, examination assessments, as well as other extra-curricular activities.

In terms of the work of class teacher, the participants are normally assigned as the assistant class teacher of a certain class. He/she is expected to take over some of the class teacher’s tasks, such as offering students necessary help concerning their daily life and learning, managing and maintaining classroom orders, getting to know the students well, and some other administrative works.

In general, the participants should follow the rules and regulations of the vocational schools where they do their internship and obey the guidance of the instructor. They should assist the instructor and class teacher (sometimes they are one single person) as much as they can in the framework of school rules and internship regulations.

Before the internship comes to an end, the participant should video record his/her own teaching during the class and the video should be uninterrupted and last at least 40 minutes. The videos are documented and stored in the college/university and can be as a reference for evaluation of the participants as well as for further analysis of the teaching.

3.1.3 Graduation

In the college interviewed, it is compulsory for the students (future teachers) to participate in the program, because they actually obtain academic credits from the internship which are necessary for the academic degree.

After the internship, during the summary week, the participants should deliver an internship report to the college/university where they study. The internship report should include: the basic introduction of the internship school (size, specialities, subjects, requirements on the intern, training institution and methods etc.), the main contents of the internship, the analysis of the teaching of the instructor, ideas and thoughts about each domain of activities (teaching, class teacher tasks), reflection on the intern’s own jobs, suggestion on the program.

The instructor writes an appraisal opinion concerning the participants’ work during the internship. This report of opinion shall be comprehensive and include different aspects of the particpants’ work, including attitude, teaching abilities and competence as a class teacher, etc.

The evaluation of the performance of the participant is dependent on several factors: the appraisal opinion given by the instructor, the opinion of the supervisor from the college/university, the assessment of the video record of the teaching and the internship report written by the participant. The performance ranking includes five categories: excellent, good, normal, pass and fail. Some institutions set a limit to the percentage of participants who get the rate of “excellent”.

According to the rules set by one teacher education institution in Shanghai, the participants in PTP1 are not allowed to graduate under the following conditions:

If they do not take the teaching job during internship seriously and fail to accomplish the assigned teaching task during the internship;

If they do not take the class-teacher job during internship seriously and fail to accomplish the assigned class-teacher task during the internship;

If they do not write the internship report seriously or plagiarise;

If they are absent from the internship for longer than 1/3 of the time;

If they seriously violate the internship discipline and cause bad consequences;

If they change the institution of internship privately.

3.2 PTP2

3.2.1 Participants

The participants of PTP2 are currently new teachers who just enter the vocational school. Since the program normally lasts for over a year (more details below), young teachers who started their teaching career for less then 2 years are also involved in the program.

3.2.2 Curriculum and Teaching

As mentioned above, no national regulation exist concerning PTP2. The local governments

The Shanghai Education Commission has advocated in their 16th document of 2011, a proposal which is attempted to boost TVET teacher training from 2011 to 2015, that a special institution for new entrants to the TVET teaching force shall be established (Shanghai Education Commission, 2011). Concrete plans and programs are under design, which will first focus on the training of basic ideas of modern vocational education, the foster of teacher ethics, the improvement of core skills for teacher and teaching abilities. According to the person who’s responsible for the TVET teacher training programs inside Shanghai Education Commission, the major forms will be apprenticeship of teachers, the mentor supervision institution as well as school-enterprise cooperation.

The program being planned will probably cover the following basic modules: (1) basic TVET theory, which offers the teachers a basic overview about the world of vocational education and its theory; (2) basic condition of vocational education in China, which gives the young teachers a better knowledge about the status quo of vocational education in China, its fundamental position in the economy and society, its major difficulties and challenges; (3) introduction to vocational schools, which makes the trainees know better about the concrete situation of vocational schools as well as the students they will face; (4) teaching methods for vocational education, which introduces to the new teachers important teaching methods systematically and exemplarily. It is intended that the first three modules are mainly provided by academic researchers while the last module will be provided by experienced vocational school teachers.

Besides the programs under consideration, the Shanghai Education Commission has taken measures to offer training to those fresh teachers who will take up the class teacher job in their schools. This training lasts for four days and mainly gives teachers basic knowledge about the nature of the class teacher’s work. However this program is limited to the domain of class teacher and has little relevance to the general preparation of vocational school teachers on a broad basis.

On the city level (the Chinese governments have five vertical levels: central government, provincial, city and county; the Shanghai government is of provincial level), some education bureaus in separate districts in Shanghai have launched programs for all novice teachers, in general schools as well as vocational schools. These programs mainly offer training during the probationary period on basic education virtue, teacher’s ethical codes, teaching methods and psychological guidance etc. However these are not specifically designed for vocational school teachers.

The mainstream of PTP2 programs now run largely on a school basis. Each school has its own power and rights as to how to train the new entrants to the schools and help them get integrated to their new jobs. Nevertheless the schools that are interviewed in this study share a lot in common in the structure, basic arrangements, and philosophy of the PTP2 program.

The new teachers to a vocational school are normally assigned a mentor who teaches the same subject. Sometimes if they need to take up the class teacher task a second mentor is assigned (of course the tow mentors can be one person). Simply put, the core task of the mentor is to help the novice get familiar with the school and teaching task and become integrated to the teacher community as soon as possible.

Several measures of quality insurance and assessment are widely taken by the vocational schools concerning this apprentice-learning. It is commonly required that the novice teacher should attend the mentor’s class on a weekly basis. Some schools set the overall requirement on the hours as to how much the novice should attend other teachers’ classes. He/she should observe the class teaching carefully, take notes and learn the teaching methods applied. Some schools require that the novice should take notes on a given form by the school and give the notes to the mentor or department for teacher development. Some schools demand that the novice teacher should report to the mentor regularly about the learning progress. The mentor is also asked to attend the novice’s class and give suggestions for improvements based on the performance.

Some more administrative methods are utilised to facilitate the transition period of the novice teachers. Some schools ask the new entrants to stay in school during the entire working hours (normally eight hours a day) for the first two years, although the rest of the subject teachers do not have to do this. This is intended to help the fresh teachers get integrated to the work environment faster. Some schools assign less teaching work for the new-comers so that they can have more time and space to learn teaching before they may be able to master it. In some schools the new teachers are assigned as the deputy class teacher, as during the PTP1 program, so that they can get to know the school and students better.

Some additional programs are implemented in individual schools. In some schools seminars on teaching are held regularly by the novice teachers. They could discuss the difficulties and challenges they are encountered with in the daily teaching; methods such as brainstorming are used to encourage the discussions among the new entrants. However these new methods are still not well established and widely used. A institution as to how these programs can be organised and systematised is still absent.

3.2.3 Graduation

Strictly speaking there’s no such thing as graduation from a program as PTP2, since the teachers will almost certainly continue teaching in the schools. However an evaluation process is always carried out at the end of the probationary period in each of the schools interviewed and they also have much commonality in this regard.

Firstly the evaluation of the PTP2 is largely practice-oriented, namely that the novice teachers are assessed according to their actual teaching performance. Normally it takes the form of a “public lecture”, where the mentor and other teachers in the vocational schools are invited to attend and assess the performance and give the novice teacher suggestions for further improvement.

Secondly the new teacher should hand in different kinds of reports concerning the“apprenticeship” learning period. These include one or two annual report(s), a paper on teaching, as well as a learning report (at the end of this program). The annual report and the learning report are to a certain degree similar, with the first one being on an annual basis. It is recommended in some schools that the paper on teaching shall achieve certain academic level so that it can be published on the school newsletter or even academic journal.

The mentor also gives assessments about the novice teacher to the human resource department every six months or each year, depending on the school situation. The assessments from the mentor are critical in judging the quality of the probationary period,although normally most teachers have no problem starting the official service.

Some schools the outstanding novice teachers are selected among all new entrants and rewarded with the honor of “excellent probationary teacher”, which can be helpful for their future career development. The main criterion according to which this honor is given is the assessment of the mentor.

4 Financing

The major costs for PTP1 is the payments for the instructors in vocational schools. The institution where the teacher candidate study pays a certain amount of money to the instructor for each student they guide and support (300 RMB Yuan per student). This money is from the university/college budget and is specially used for student internships and similar purposes.

However this payment is normally given centrally from the teacher training college to the vocational school, how the vocational school distribute it to the instructors is unclear.

In general the cost for PTP2 is not very high since most of the tasks are accomplished by the novice teacher him/herself and the mentor. The schools normally pay the mentor some extra money for this task but it is rather modest according to the interviewed teachers (some 200 RMB Yuan per month).

For PTP2 that is under design on the provincial level, the Shanghai government has established special funding for the entire program. Individual schools and participants will not need to worry about the costs. Currently in the government agenda, great emphasis has been laid on the teacher training and development in vocational education, therefore it is safe to predict that there’ll be sufficient funding for the upcoming program.

As for the PTP2 program running on the school level. The situation differs from school to school. This is related to the background of the school. Some vocational schools are administrated by the Shanghai Education Commission, whereas some of them are affiliated to the corresponding industry or even certain state-owned-enterprises. Thus the resources available to them are different. In some schools they may have special funding for the PTP2 programs, in some other ones the schools may have to use other funding sources (such as extra money from school owned business) for this program.

5 Outcome

5.1 PTP1

The overall outcome of PTP1 is positive according to the assessment appraisals about the teacher candidates written by the instructors. The practical abilities of the candidates are generally improved during the internship. The candidates themselves also report that they have gained better understanding for as well as ability of teaching in real classroom circumstances.

Some of the instructors may write something negative about the teacher candidate if they are not always present for the internship. For some instructors, the attitude of the future teacher is more important than the professional competences. And some teacher candidates have given negative impressions in this respect.

One factor that negatively influence the outcome of the PTP1 is the timing of the program. It is arranged at the second half of the 7th semester for four-year university students (teacher candidates) and this period is also crucial for students because it is perfect time for job-hunting and preparing for master program entrance examinations. Many students cannot devote their time and energy for the internship in the vocational schools since they are looking for jobs, going to job interviews, or learning the exam subjects. This conflict of time is hardly solvable due to the tight arrangements of the bachelor program itself. It is extremely difficult for the teacher education institution to find another time for this internship. The consequence is that some students are sometimes absent from the internship and the effectiveness of program is jeopardised.

Another influencing factor on PTP1 is the vocational school. Some vocational schools view the interns from the college/university as well-trained human resources that can be utilised for its own interests. They ask the interns to do various jobs that is more than necessary for training. So the interns correct homework of the students, give classes, and prepare paperwork for the leaders of the vocational schools, etc., and receive little guidance. The training of the teacher candidates is therefore ignored and the program is disadvantaged.

5.2 PTP2

As for PTP2, the interviewed teachers state that in general the program make substantial contribution to the integration of new entrants to the teaching job. The improvement of the novice teachers are all-round:through the PTP2 program the participants have gained basic impression and knowledge about vocational schools; they have obtained understanding about the organisation structure of the school, including how the school works; they have improved their teaching skills and ability to manage a class; they have got more familiar with the students. But most significantly, their practical competences in dealing with everyday teacher jobs have been strengthened.

This positive outcome is in accordance with the initial purpose of the PTP2 program, namely to introduce the new entrant to the world of work as a teacher and to improve their practical skills.

However some different voices are also expressed during the interview concerning the effectiveness of PTP2.

The pertinence of the program is questioned. Because the entire training programs is initiated and organised by the department of personnel or teacher development and the operation is largely on an administrative and bureaucratic basis, the program can hardly meet the real needs of the novice teachers. No preliminary empirical study is carried out to find out the demands of the new teachers. The design and structure of the training program is to a great extent based on impulsive decision making of the responsible person. In some occasions, when it is not obligatory for all novice teachers to participate in the programs, the head of department of personnel simply assign the “training task” to the teachers without getting to know the real needs of them. This problem is related to the administration and management of vocational schools in general and is therefore not easy to solve with technical solutions (Li and Pilz, 2011).

The emphasis of the program is also doubted by the interviewed teachers. Some schools attach great importance to the training of teacher’s ethic codes and to a certain degree neglect the training of the professional competences such as teaching methods and subject didactics. Because many of the students of vocational schools have difficulties in learning academic subjects and often conduct undisciplined behaviours, some vocational schools therefore regard the moral and management aspects of a teacher as the most influential factor affecting the school’s performance. This unbalanced emphasis is reflected in the training programs and is not beneficial to the long term development of the teachers.

One other negative outcome mentioned by the teachers is that the influence of the mentor on the novice teacher may be too predominant that the teaching style and methods of the novice teacher can be limited. Due to the fact that the major guidance a new entrant gets is from the mentor and the mentor has certain power in judging the performance of the novice teacher, the novice teacher has to follow closely what the mentor says and does; this could constrain the innovation of the new teacher. The possibility of improving the existing teaching system is also therefore restricted.

6 Summary, Reflections and Implications

In summary, as the text above described, the PTP program for vocational school teachers in China is in general effective and the participating parties and individuals have benefited from the program: the vocational schools have made the new recruited teachers get integrated to their school in a reasonable time frame; the teacher education institutions have found a way to make their students better candidates for the future teacher career; the teacher candidates or novice teachers have improved their competences and become more prepared for the teaching job.

In terms of the content of the curriculum, both PTP1 and PTP2 are strongly practice-oriented. There’s no clearly defined structure of the curriculum of the program and the participants learn mainly in an apprenticeship style and on an observation-imitation basis.

When it comes to the participation rate, most teacher candidates and novice teachers take part in the PTP programs. Besides studying in the corresponding institution or being the teacher in the schools, no special requisites exist for entering the programs. To finish the program successfully one needs to take part in the programas required and write certain reports and some other tasks, such as video record the teaching, filling in some forms, etc., which are not remarkably difficult.

In Shanghai the financing of both PTP1 and PTP2 presents no major difficulties. Special funds come from either the teacher education institutions or government supports. Some schools may have better financial resources than the others but no school interviewed has mentioned any trouble with money. However this situation in Shanghai cannot be generalised to other regions in China.

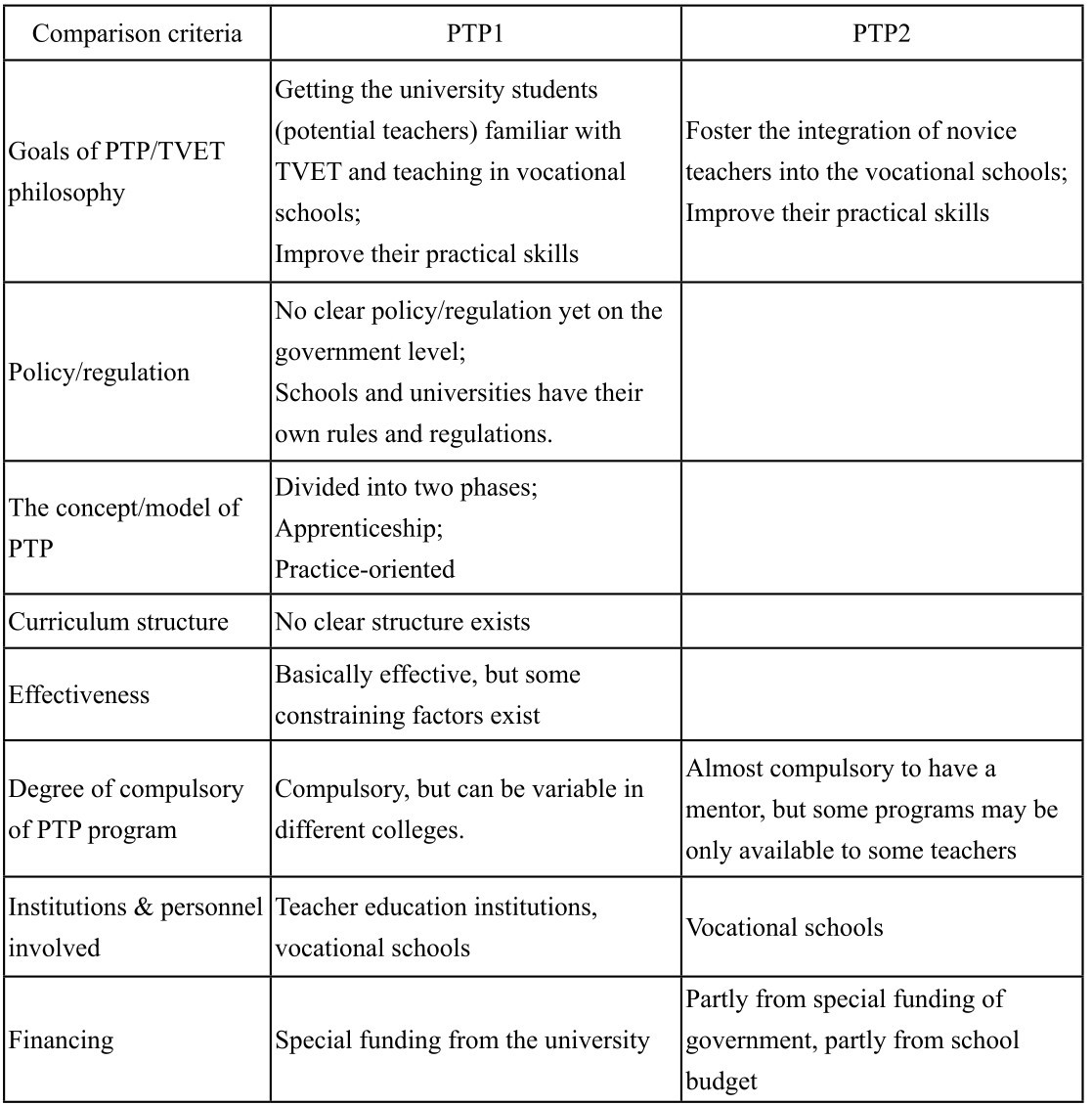

The key characteristics of the PTP programs in China are summarised in the following table (Tab.1), in order to illustrate their major features in comparison to PTP programs in other countries.

Tab.1 The Key Characteristics of the PTP Programs in China

Despite the general effectiveness of the PTP program, some problems deserve some deeper investigation and reflections.

Firstly, the lack of clearly defined curriculum structure and contents of the program could lead to great difficulty in quality assurance, management and evaluation. The teacher education institutions and the vocational schools will largely determine the quality of the programs. The contribution of this program to individual participants depends heavily on the attitude and competence of individual instructors and mentors. Some empirical work would be valuable in finding out the real effectiveness of the program on an individual level. Based on this empirical work and appropriate academic design, a clearly defined curriculum could strengthen the the program’s quality and its management.

Secondly, the absence of policy and regulation on the government level further increase the uncertainty of the quality of the programs. The schools are on their own in making decisions about the programs and the intern’s education rights are not always guaranteed. Students may be used as cheap labours in the schools while their education and training is partially neglected. Better policy and regulation by the authority that clearly stipulates the rights and responsibilities of all involved parties could potentially protect the students better as well as maintain order and quality of the programs.

If a clearly defined curriculum and policy/regulation are both in position, the mentor could be less influential on the program as a whole. Novice teachers would probably have alternative sources of guidance and supports.

Thirdly, as mentioned above, the current administrative structure and decision-making process in Chinese education system could jeopardise the pertinence as well as the value of the programs, because the real demands from the major customers- the novice teachers can not be fully appreciated by and communicated to the decision makers. Some reform on the administrative culture and structure would be needed to change this situation.

7 Additional Notes about Industry Training Program for Young Teachers

Besides the programs introduced above, one additional program that is being carried out also deserves mentioning, although it does not fit the title of this study thoroughly.

The program which is called “Industry practice for young vocational schools teachers” (here referred to as IPT) is a part of the programs initiated by the ministry of education that intends to promote the overall quality of vocational school teachers. According to the guideline set by the ministry of education, some comanies (numbers of which vary from less than 10 to about 30) are assigned as the practice certers for young vocational teachers in each province. Each company has a task of receiving varied number of young teachers from vocational schools. The general purpose is to foster the industry related skills of the VET teachers (Ministry of Education China, 2012).

However, the concrete programs and contents of the training are not clearly stated; the definition of “young teachers” is also not seen in this program; the financing as well as the selection procedure is not mentioned either. It is estimated that the ministry has a funding specially allocated for this program. As a pilot project, the IPT program is still more or less in a phase of exploration. A more systematic apporach is probably still under development, but due to the lack of valid source of information other than the documents online, the real direction where this program is heading for is not clear.

Remarks

Number of vocational school teachers interviewed: 5

The vocational schools they work at: Zhonghua Vocational School, Shanghai Industrial and Commercial Foreign Language School, Shanghai Municipal Health School, Shanghai Food Science and Technology School, Shanghai Electronic Industrial School.

Information about the interviewed personnel in government institution:

He works in an organisation responsible for the vocational teacher training in Shanghai, this organisation is affiliated to Shanghai Education Commission.

References

Ding, G., Sun, M. 2007. The qualifications of the teacher force in China. In: Ingersoll, R. A Comparative Study of Teacher Preparation and Qualifications in Six Nations. Consortium for Policy Research in Education. http://www.cpre.org/sites/default/files/policybrief/887_rb47.pdf

Eighth National People’s Congress .1993. Teachers Law of the People’s Republic of China. http://www.moe.edu.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_2803/200907/49852.html (attained at 16.06.2012).

Eighth National People’s Congress. 1995. Education Law of the People’s Republic of China. http://www.moe.edu.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_2803/200905/48457.html (attained at 16.06.2012).

Li, J., Pilz, M. 2011. Berufsbildung in der Volksrepublik China. In: Kreklau, C., Siegers, J. Handbuch der Aus- und Weiterbildung (219. Ergänzungslieferung, August 2011), Köln: Wolters/Kluwer.

Ministry of Education China. 2012. Notice about the task 2011 of promotion of vocational school teachers’ quality by Ministry of Education. http://www.moe.edu.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_960/201206/xxgk_137344.html (attained at 03.07.2012). Original in Chinese.

Pan, C., Li, M., Lou, W. 2007. The development and challenges of the Chinese vocational education. A survey in 32 vocational schools and colleges. Chinese population science, 2: 52-60.

Shanghai Education Commission. 2011. Action plan for training of secondary vocational school teachers in Shanghai (2011-2015). http://www.shanghai.gov.cn/shanghai/node2314/node2319/node12344/u26ai25622.html.

Xu, S. 2004. Die chinesische Berufsbildung und ihr historisch-kultureller Hintergrund. Die berufsbildende Schule, 56 (3/4): 78-83.