Chapter 22 The Flavor of Meat

Flavor is a very important component of the eating quality of meat and there has been much research aimed at understanding the chemistry of meat flavor, and at determining those factors during the production and processing of meat which influence flavor quality. The desirable characteristics of meat flavor have also been sought in the production of simulated meat flavorings which are of considerable importance in convenience and processed savory foods.

Meat flavor is thermally derived, since uncooked meat has little or no aroma and only a blood-like taste. During cooking, a complex series of thermally induced reactions occur between non-volatile components of lean and fatty tissues resulting in a large number of reaction products. Although the flavor of cooked meat is influenced by compounds contributing to the sense of taste, it is the volatile compounds, formed during cooking, that determine the aroma attributes and contribute most to the characteristic flavors of meat. As of now 1000 volatile compounds have been identified.

Meat Flavor Precursors

The main reactions during cooking, which result in aroma volatiles, are the Maillard reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars, and the thermal degradation of lipid.

The main water-soluble flavor precursors were suggested to be free sugars, sugar phosphates, nucleotide bound sugars, free amino acids, peptides, nucleotides, and other nitrogenous components, such as thiamine. Reductions in the quantities of carbohydrates and amino acids were observed during heating, the most significant losses occurring for cysteine and ribose. In muscle, ribose is one of the main sugars where it is associated with the ribonucleotides , in particular, adenosine triphosphate. This nucleotide is essential for muscle function and, post-slaughter, it is converted to inosine monophosphate. Studies of the aromas produced on heating mixtures of amino acids and sugars, confirmed the important role played by cysteine and ribose in meat flavor formation and led to the classic patent of Morton et al. in 1960 (GB Patent 836,694) which involved the formation of a meat-like flavor by heating a mixture of these compounds. Most subsequent patent proposals for “reaction product” meat flavorings have involved sulfur, usually as cysteine or other sulfur-containing amino acids or hydrogen sulfide. Several hundred volatile compounds derived from lipid degradation have been found in cooked meat, including aliphatic hydrocarbons, aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, carboxylic acids and esters.

Volatiles from the Maillard Reaction

The Maillard reaction, which occurs between amino compounds and reducing sugars, is one of the most important routes to flavor compounds in cooked foods, including meat. This reaction is complex and provides a large number of compounds which contribute to flavor. The initial stages of the reaction involve the condensation of the carbonyl group of the reducing sugar with the amino compound, to give a glycosylamine. Subsequently, this rearranges and dehydrates, via deoxyosones, to various sugar dehydration and degradation products such as furfural and furanone derivatives, hydroxyketones and dicarbonyl compounds. Although the reaction has been discussed in many research papers, it is interesting to note that the mechanism proposed by Hodge in 1953 still provides the basis for our understanding of the early stages of this reaction.

The subsequent stages of the Maillard reaction involve the interaction of these compounds with other reactive components such as amines, amino acids, aldehydes, hydrogen sulfide and ammonia. These steps provide the aroma compounds which characterize cooked foods and, therefore, are of particular interest to the flavor chemist. An important associated reaction is the Strecker degradation of amino acids by dicarbonyl compounds formed in the Maillard reaction.

The amino acid is decarboxylated and deaminated forming an aldehyde, while the dicarbonyl is converted to an a-aminoketone or aminoalcohol. If the amino acid is cysteine, Strecker degradation can also lead to the production of hydrogen sulfide, ammonia and acetaldehyde. These compounds, together with carbonyl compounds produced in the Maillard reaction, provide a rich source of intermediates for further flavor-forming reactions. These lead to many important classes of flavor compounds including furans, pyrazines, pyrroles, oxazoles, thiophenes, thiazoles and other heterocyclic compounds. Sulfur-compounds derived from ribose and cysteine, seem to be particularly important for the characteristic aroma of meat. In meat, the main sources of ribose are inosine monophosphate and other ribonucleotides.

Compounds Contributing to Roast and Boiled Aromas

Roast flavors in foods are usually associated with the presence of heterocyclic compounds such as pyrazines, thiazoles and oxazoles. Many different alkyl pyrazines have been found in meat volatiles as well as two classes of interesting bicyclic compounds, 6,7-dihydro-5(H)-cyclopentapyrazines and pyrrolopyrazines. This latter class of compounds has not been reported in any other food. Alkyl-substituted thiazoles, in general, have lower odor thresholds than pyrazines, although they are found at lower concentrations in meat. Both classes of compound increase markedly with the increasing severity of the heat treatment and, in well-done grilled meat, pyrazines were reported to be the major class of volatiles.

A probable route to the formation of alkylpyrazines is from the condensation of twoa-aminoketone molecules produced in the Strecker degradation of amino acids by dicarbonyl compounds. This also involves a-dicarbonyls, or hydroxyketones, and their reaction with hydrogen sulfide and ammonia, formed via the hydrolysis or Strecker degradation of cysteine, and an aldehyde.

One notable feature of the volatiles from cooked meat is the preponderance of sulfur-containing compounds. The majority occurs at low concentrations, but their very low odor thresholds make them potent aroma compounds and important contributors to the aromas of cooked meat. A comparison of boiled and roast beef shows that many more aliphatic thiols, sulfides and disulfides have been reported in boiled meat. Heterocyclic compounds with 1, 2 or 3 sulfur atoms in 5 and 6 membered rings (e. g. , thiophenes, trithiolanes, trithianes) are much more prevalent in boiled than in roast meat. Many of these sulfur compounds have low odor thresholds with sulfurous, onion-like and, sometimes, meaty aromas, and they probably contribute to the overall flavor by providing sulfurous notes which form part of the aroma of boiled meat.

“Meaty” Flavors of Cooked Meat

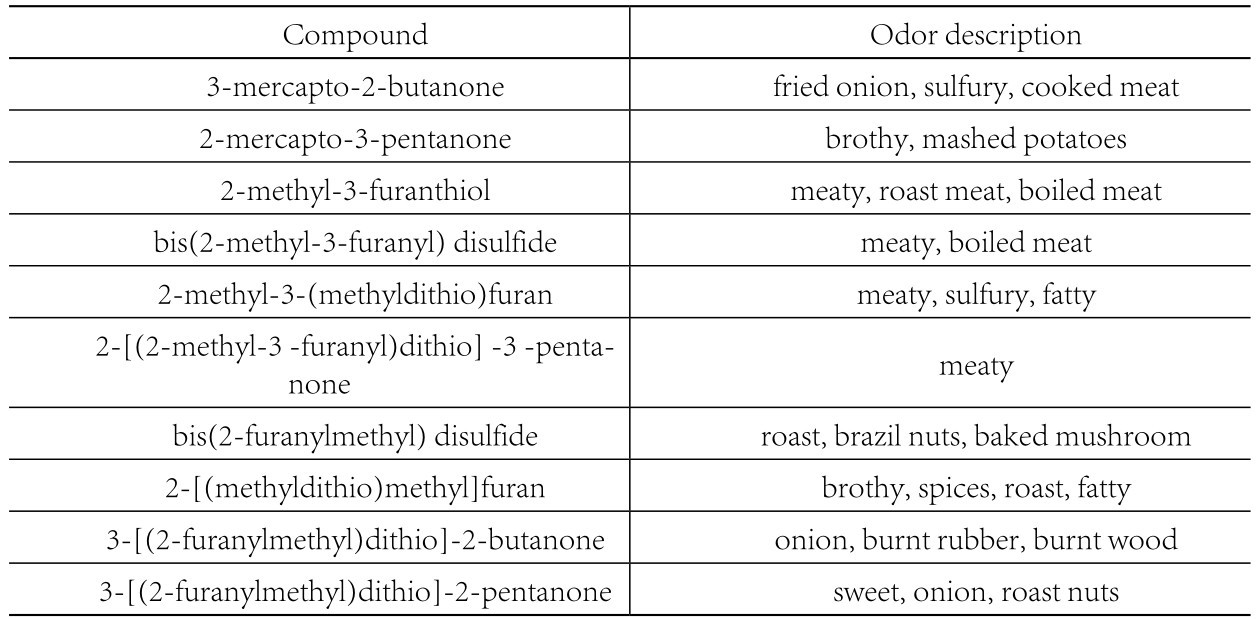

All cooked meats possess a desirable “meaty” aroma and the identification of compounds with such characteristics has been the subject of a large amount of research, much of which has been driven by the requirement for simulated meat flavorings for use in processed savory food products. It has been known for some time that furans and thiophenes with a thiol group in the 3-position, and related disulfides, possess strong meat-like aromas and exceptionally low odor threshold values. However, it was not until relatively recently that such compounds were first reported in meat itself. Mac Leod and Ames identified 2-methyl-3-(methylthio)furan in cooked beef in 1986. It has been reported to have a low odor threshold value (0. 05 ug/kg) and a meaty aroma at levels below 1 ug/kg. Gasser and Grosch (1988) identified 2-methyl-3-furanthiol and the corresponding disulfide, bis (2-methyl-3-fiiranyl) disulfide, as major contributors to the meaty aroma of cooked beef. The odor threshold value of this disulfide has been reported as 0. 02ng/kg, one of the lowest known threshold values. Other thiols and disulfides, containing, 2-furanylmethyl moieties have also been found in the volatiles of heated meat systems. Evaluation of the aromas of these compounds, by odor-port sniffing as they eluted from the gas chromatography column, indicated meaty characteristics for compounds containing 2-methyl-3-furanyl groups, while those with 2-methylfuranyl groups had roast, nutty, burnt characteristics. This is in agreement with earlier observations that furans with a thiol or sulfide group in the 3-position on the ring, possessed meaty odors. These meaty and nutty aromas are detected at low concentrations (< 1 ug/kg), but at higher concentrations, the aromas are perceived as sulfurous and objectionable.

Odors of some thiols and disulfides were evaluated in cooked meat volatiles by GC odor-port assessment (Madruga, 1994).

The routes involved in the formation of the various furan sulfides and disulfides are likely to be the interaction of hydrogen sulfide with dicarbonyls, furanones and furfurals to give thiols and mercaptoketones. Oxidation of these thiols then results in mixtures of symmetrical and unsymmetrical disulfides. A number of such compounds are formed in heated model systems containing hydrogen sulfide or cysteine and pentoses or other sources of carbonyl compounds, and in the thermal degradation of thiamine. In meat, it has been proposed that ribose phosphate, from the ribonucleotides, is the principal precursor of furan and thiophenethiols. Dephosphorylation and dehydration of ribose phosphate form the important intermediate 4-hydroxy-5-methyl-3(2H)-furanone, which readily reacts with hydrogen sulfide .