Chapter 15 Lithium-Ion Battery Research

The motivation for using a battery technology based on Li metal as anode relied initially on the fact that Li is the most electropositive (-3.04 V versus standard hydrogen electrode) as well as the lightest (specific gravity p = 0.53g • cm-3) metal, thus facilitating the design of storage systems with high energy density. The advantage in using Li metal was first demonstrated in the 1970s with the assembly of primary (for example, non-rechargeable) Li cells. Owing to their high capacity and variable discharge rate, they rapidly found applications as power sources for watches, calculators or for implantable medical devices. Over the same period, numerous inorganic compounds were shown to react with alkali metals in a reversible way. The discovery of such materials, which were later identified as intercalation compounds, was crucial in the development of high-energy rechargeable Li systems. Like most innovations, development of the technology resulted from several contributions. By 1972, the concept of electrochemical intercalation and its potential use were clearly defined, although the information was not widely disseminated, being reported only in conference proceedings. Before this time, solid-state chemists had been accumulating structural data on the inorganic layered chalcogenides, and merging between the two communities was immediate and fruitful.

Early Technical Hurdles

In 1972, Exxon Company embarked on a large project using Ti S2as the positive electrode, Li metal as the negative electrode and Li Cl O4in CH2OCH2OCH2as the electrolyte. Ti S2was the best intercalation compound available at the time, having a very favorable layered-type structure. As the results were published in Science (in 1976) and as a US patent, this work convinced a wider audience. But in spite of the impeccable operation of the positive electrode, the system was not viable. It soon encountered the shortcomings of a Li metal/liquid electrolyte combination-uneven(dendritic) Li growth as the metal was replated during each subsequent discharge-recharge cycle, which led to explosion hazards. Substituting Li metal for an alloy with A1 solved the dendrite problem but, as discussed later, alloy electrodes survived only a limited number of cycles owing to extreme changes in volume during operation. In the meantime, significant advances in intercalation materials had occurred around 1974 with the realization at Bell Laboratories that oxides, besides their early interest for the heavier chalcogenides, were giving higher capacities and voltages. Moreover, the previously held belief that only low-dimensional materials could give sufficient ion diffusion disappeared as a framework structure (V6O13) proved to function perfectly in 1979. Later, John Goodenough at the University of Texas (Austin) proposed from 1980-1983 the families of compounds with Lix MO2(where M is Co, Ni or Mn), that are still used almost exclusively in today’s batteries.

To circumvent the safety issues surrounding the use of Li metal, several alternative approaches were pursued in which either the electrolyte or the negative electrode was modified. The first approach involved substituting metallic Li for a second insertion material. The concept was first demonstrated in the laboratory by Murphy et al. and then by Scrosati et al. and led, at the end of the 1980s and early 1990s, to the so-called Li-ion or rocking-chair technology. The principle of rocking-chair batteries had been used previously in Ni-Me H batteries. Because of the presence of Li in its ionic rather than metallic state, Li-ion cells solve the dendrite problem and are, in principle, inherently safer than Li-metal cells. To compensate for the increase in potential of the negative electrode, high-potential insertion compounds are needed for the positive electrode, and emphasis shifted from the layered-type transition-metal disulphides to layered or three-dimensional- type transition-metal oxides. Metal oxides are more oxidizing than disulphides (for example, they have a higher insertion potential) owing to the more pronounced ionic character of “M -O” bonds compared with “M -S” bonds. Nevertheless, it took almost ten years to implement the Li-ion concept. Delays were attributed to the lack of suitable materials for the negative electrode (either Li alloys or insertion compounds) and the failure of electrolytes to meet-besides safety measures-the costs and performance requirements for a battery technology to succeed. Finally, capitalizing on earlier findings, the discovery of the highly reversible, low voltage Li intercalation-deintercalation process in carbonaceous material (providing that carefully selected electrolytes are used), led to the creation of the C/Li Co O2 rocking-chair cell commercialized by Sony Corporation in June 1991. This type of Li-ion cell, having a potential exceeding 3.6 V (three times that of alkaline systems) and gravimetric energy densities as high as 120-150 W•h• kg-1 (two to three times those of usual Ni-Cd batteries), is found in most of today’s high-performance portable electronic devices.

The second approach involved replacing the liquid electrolyte by a dry polymer electrolyte, leading to the so-called Li solid polymer electrolyte (Li-SPE) batteries. But this technology is restricted to large systems (electric traction or backup power) and not to portable devices, as it requires temperatures up to 80℃. Shortly after this, several groups tried to develop a Li hybrid polymer electrolyte (Li-HPE) battery, hoping to benefit from the advantages of polymer electrolyte technology without the hazards associated with the use of Li metal. “Hybrid” meant that the electrolyte included three components: a polymer matrix swollen with liquid solvent and a salt. Companies such as Valence and Danionics were involved in developing these polymer batteries, but HPE systems never materialized at the industrial scale because Li-metal dendrites were still a safety issue.

Thin Film Lithium Batteries

With the aim of combining the recent commercial success enjoyed by liquid Li-ion batteries with the manufacturing advantages presented by the polymer technology, Bellcore researchers introduced polymeric electrolytes in a liquid Li-ion system in 1996. They developed the first reliable and practical rechargeable Li-ion HPE battery, called plastic Li-ion (PLi ON), which differs considerably from the usual coin-, cylindrical- or prismatic-type cell configurations. Such a thin-film battery technology, which offers shape versatility, flexibility and lightness, has been developed commercially since 1999, and has many potential advantages in the continuing trend towards electronic miniaturization. Finally, the “next generation” of bonded liquid electrolyte Li-ion cells, derived from the plastic Li-ion concept, are beginning to enter the market place. Confusingly called Li-ion polymer batteries, these new cells use a gel-coated, microporous polyolefin separator bonded to the electrodes (also gel-laden), rather than the P(VDF-HFP)-based membrane (that is, a copolymer of vinylidene difluoride with hexafluoropropylene) used in the plastic Li-ion cells.

General Electrochemical Reactions in Li-ion Batteries

The three participants in the electrochemical reactions in a lithium-ion battery are the anode, cathode, and electrolyte. Both the anode and cathode are materials into which and from which lithium can migrate. The process of lithium moving into the anode or cathode is referred to as insertion (or intercalation), and the reverse process, in which lithium moves out of the anode or cathode is referred to as extraction (or deintercalation). When a lithium-based cell is discharging, the lithium is extracted from the anode and inserted into the cathode. When the cell is charging, the reverse process occurs: lithium is extracted from the cathode and inserted into the anode. The anode of a conventional Li-ion cell is made from carbon, the cathode is a metal oxide, and the electrolyte is a lithium salt in an organic solvent.

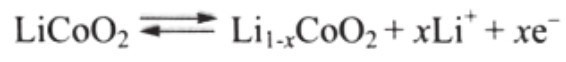

Useful work can only be extracted if electrons flow through a (closed) external circuit. The following equations are written in units of moles, making it possible to use the coefficient x. The cathode half-reaction (with charging being forward) is:

The anode half reaction is:

The overall reaction has its limits. Over-discharge will supersaturate lithium cobalt oxide, leading to the production of lithium oxide, possibly by the following irreversible reaction:

Overcharge up to 5.2 V leads to the synthesis of cobalt (IV) oxide, ats evidenced by X-ray diffraction:

In a Li-ion battery, the lithium ions are transported to and from the cathode or anode, with the transition metal, Co, in Li;c Co O2being oxidized from Co3+to Co4+ during charging, and reduced from Co4+to Co3+during discharging.

When the battery is discharged, the lithium ions in the anode material migrate to the cathode material, and a discharging current flows; while the battery is charged, the lithium ions in the cathode material migrate between the layers of material to form the anode, and a charging current flows.