Chapter 9 Reactive Noble Gases

Until 1960s, noble gases, also known as rare gases, had been recognized as chemically stable, unreactive elements. Their nicknames, inert gases, had been used in scientific literature, textbooks, as well as in industry throughout the world. The unique inert property derives from their stable electronic structure. The outermost electron shells of Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe, and Rn all have eight electrons, with no propensity to acquire or lose electrons to form a compound. Thus, for decades after their discovery, the inert gases had been used as chemically unreactive substances.

Although classical valence theory precluded noble gases from chemical reactions, a few quantum chemists envisaged that extremely reactive fluorine might form compounds with xenon, whose outer electrons were only loosely bound because of its large atomic radius. In 1962 Neil Bartlett working at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, reported that he had the first compound of a noble gas (xenon), Xe+[Pt F6]-. Bartlett’s work amazed the science community instantly and stimulated researchers to further explore more noble gas compounds.

Bartlett used to investigate the oxidizing capabilities of fluorine compounds with O2+, the pentavalent gold compound Au F6-, and the unstable high oxidation state fluorides Ni F4and Ag F3, the latter being strong fluorinating reagents. Several years ago, he had unexpectedly obtained a deep-red solid during an experiment with platinum and fluorine, with unknown chemical composition at the time. He and his first doctoral student, Derek Lohmann fervently identified its composition, and eventually established that the gaseous platinum hexafluoride (Pt F6), was able to oxidize oxygen and produce the red solid, which they identified as O2Pt F6.

Pt + 3 F2→Pt F6

Pt F6+ O2→ O2Pt F6

The most bizarre result from this study was that oxygen appears in the form of positively charged cations, instead of commonly seen negative anion. In general oxygen gains electrons from other atoms and is well recognized as an oxidizing agent. But Bartlett supposed that in this abnormal red compound, the Pt F6component acted as a more powerful oxidant than oxygen and removed electrons from oxygen. Not until Bartlett’s research had the oxidizing power of Pt F6been recognized, despite its first synthesis was achieved at Argonne National Laboratory a few years before. This result led Bartlett to hypothesize that the strong oxidizing property of Pt F6could oxidize xenon gas which has a first ionization potential (the energy necessary to remove the first electron) very close to that of oxygen.

In March of 1962, Bartlett started a new experiment to test this assumption. In a glass apparatus, red Pt F6vapor was introduced into one chamber, while colorless xenon gas was brought into an adjoining chamber separated from the first one by a seal. In the evening at dinner time of Friday, March 23rd, Bartlett began to mix the two gases with the same pressure by breaking the seal between the two gases, and an instant reaction occurred at room temperature, with an orange colored solid precipitated and the system pressure lowered. The reaction took place in a split second and was “extraordinarily exhilarating”, as he later recalled. He had no doubt that the solid was the first noble gas salt, xenon hexafluoroplatinate, Xe Pt F6, as calculated from the system pressure. The result defied the long held notion of noble gases. Bartlett believed that the novel compound was the world’s first noble gas compound. That orange solid was subsequently identified in the Bartlett group as [Xe F]+[Pt F5]-.

Sparked off by Bartlett’s work, other scientists soon repeated the experiment and within months began to synthesize new compounds from xenon, radon and krypton, such as Xe F2, Xe F4, and Xe F6. Some researchers in Argonne National Laboratory and in Germany used very high pressure F2gas to form such compounds directly with Xe. A brand new field of noble gas chemistry had been launched with the abolishment of the old “law” of their unreactivity. In October 1962, Bartlett shifted his effort to oxidize Xenon with oxygen. He and his doctoral student P. R. Rao quickly isolated an oxide. However, one of their samples exploded, resulting in a serious injury to them, so they had to be hospitalized for a month. The explosive product was later identified as Xe03 by other investigators.

More stable neutral noble gas compounds are being synthesized every year. According to Bartlett’s estimation, over 100 noble gas compounds have been known since 1962. In 2002, researchers at the University of Helsinki in Finland reported the formation of the first argon compound at cryogenic temperatures, argon fluorohydride (HAr F), by irradiating a strong ultraviolet light on frozen argon that contained a small amount of hydrogen fluoride. Helium may also form a metastable compound HHe F. No true neutral compounds of neon are known. However, the ions Ne+, (Ne Ar)+, (Ne H)+, and (He Ne+) have been detected in spectroscopic and mass spectrometric studies. These fragile compounds are energy rich: they tend to be extremely unstable and as a result highly reactive.

As of now, noble gas chemistry has become a powerful tool for developing new compounds with useful properties and already made an impact on our daily lives. One of the remarkable values is that fluorination of organic compounds can be achieved by reacting between xenon fluorides and ordinary compounds with C - H groups. For example, Xe F2 has been exploited to convert uracil to 5-fluorouracil, one of the first anti-tumor agents. Radon can be chemically scrubbed from the air in uranium mines based on its reactivity. “The important aspect of my discovery,” Bartlett says, “was to draw attention to fundamental chemical considerations-especially that quantitative energy differences are important when considering variations in the chemistry of the elements in a Periodic Table framework.”

Binary compounds of argon, krypton, or xenon are used in excimer lasers to produce monochromatic beams of ultraviolet light (when electrically stimulated) that are employed to perform eye surgery for vision repair. Pulse widths of Kr F lasers in commercial applications are typically 20-30 nanoseconds. The light from the Ar F UV laser is strongly absorbed by lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins, giving it wide applications in surgery and medical therapy. Ar F and Kr F lasers are also used in laser microlithography, where the short wavelength is desirable for etching nanometer-sized structural features. The principle behind the excimer laser emission can be briefly described as follows.

Myopia, astigmatism, and hyperopia can all be treated effectively with a non-thermally damaging and precisely controllable Ar F excimer laser beam. Right:semiconductor wafer manufacturing processes involve immersion lithography to create nanometer-sized structural patterns by using Ar F excimer laser (with a wavelength of 193 nm) or Kr F excimer laser (with a wavelength of 248 nm). Scale Bar = 1 micron.

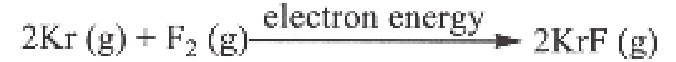

A krypton fluoride laser absorbs energy from a source, causing the krypton gas to react with the fluorine gas producing krypton fluoride complex, in an excited energy state.

Krypton fluoride is a temporary complex formed in an excited energy state

The complex is formed because the krypton atom’s unfilled outermost electronic shell in the excited state can be refilled by an electron from an adjacent krypton atom. The typical lifetime of a krypton fluoride excited state complex is only a few nanoseconds, after which the complex undergoes spontaneous or stimulated emission and reduces its energy state to a metastable, but highly repulsive ground state. The ground state complex quickly dissociates into unbounded Kr atoms.

The above process has been used to construct an exciplex (excited complex) laser that emits photons at 248 nm, which lies in the near ultraviolet portion of the spectrum.

Recently reactions between noble gases and hydrocarbons have been established, which is a further development that could bring about new and better synthetic approaches to some organic materials. Noble gas compounds also show promise as green chemistry reagents that allow for more environmentally friendly manufacturing processes. Bartlett believed even the highly fragile compounds produced in Helsinki would offer benefits as yet unforeseen. All these trace their legacy back to the pivotal moment in a chemistry laboratory at the University of British Columbia, when a clever young scientist turned conventional wisdom upside down with the help of a memorable experiment and changed the face of chemistry forever.