-

1.1扉页

-

1.2前言

-

1.3第一部分 语言与人格结构

-

1.3.1第一章 序言与介绍

-

1.3.2第二章 论词语的经济

-

1.3.3第三章 形式—语义平衡与进化过程的经济

-

1.3.4第四章 儿童言语表达与“言语的起源”

-

1.3.5第五章 作为感知与思考的语言

-

1.3.6第六章 作为参照框架“原点”的自我

-

1.3.7第七章 心智与符号过程的经济:性、文化和精神分裂症

-

1.3.8第八章 梦与艺术的语言

-

1.4第二部分 人际关系:种内平衡的案例

-

1.4.1第九章 地理经济

-

1.4.2第十章 国内合作冲突与国际合作冲突

-

1.4.3第十一章 经济权势分配与社会身份分配

-

1.4.4第十二章 声望符号与文化时尚

-

1.5参考文献

-

1.6索引

-

1.7译后记

参考文献

第一章

1. Discussed L.J.Henderson, “What is social progress?”(in A Symposium on Social Progress)Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[J], Vol.73(1940):458—463; cf.particularly p.460. Henderson cities Edgeworth, F.Y. Mathematical Physics[M]London: Kegan Paul, 1881:117 as an early source.

2. Jeremy Bentham's concept of the “greatest happiness for the greatest number”(the fallacy of which was noticed by Edgeworth, Mathematical Physics, op.cit.)is at least as old as the eighteenth century philosopher, Francis Hutcheson(cf. his Inquiry concerning Moral Good and Evil[M], 1725).

3. de Maupertuis, P.L.M. Essai de cosmologie[M]. Amsterdam, 1750. For a concise statement of the principle of least action including Hamilton's Principle, cf. J.H.Jeans, An Elementary Treatise on Theoretical Mechanics[M]. Boston: Giin, 323—328. Cf. A.Kneser, Das Prinzip der kleinsten Wirkung von Leibnitz bis zur Gegenwart[M]. Leipzig: Teubner, 1928. Also P.E.B.Jourdain, The Principle of Least Action[M]. Chicago: Open Court, 1913.

4. Zipf, G.K. “The unity of nature, least action, and social science,” Sociometry[J]. Vol.5(1942):48—62.

5. Miller, N.E. & J.Dollard, Social Learning and Imitation[M]. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1941.

6. Hull, C.L. Principles of Behavior[M]. New York: Appleton-Century, 1943.

7. Gengerelli, J.A. “The principle of maxima and minima in animal learning,” Journal of Comparative Psychology[J]. Vol.11(1930):193—236.

8. Tsai, L.S. “The laws of minimum effort and maximum satisfaction in animal behavior,” Monograph of the National Institute of Psychology[M].(Peiping, China)No.1, 1932. Abstracted in Psychological Abstracts[J]. Vol.6(1932), No.4329.(Original not seen.)

9. Waters, R.H. “The principle of least effort in learning,” Journal of General Psychology[J]. Vol.16(1937):3—20.

10. Waters, R.H. The Science of Psychology[M]. New York: Crowell, 1929:81—85. See also subsequent editions.

11. Crozier, W.J. & G.Pincus, “Analysis of the geotropic orientation of young rats, V,” Journal of General Physiology[J]. Vol.15(1932):421—462, with citations, p.462, to their previous publications on the subject.

12. Op.cit, p.294.

13. Crutchfield, R.S. “Psychological distance as a function of psychological need,” Journal of Comparative Psychology[J]. Vol.28(1939):447—469.

14. Thompson, M.E. “An experimental investigation of the gradient of reinforcement in maze learning,” Journal of Experimental Psychology[J]. Vol.34(1944):390—403.

15. For general orientation in the field of experimental psychology, cf.Boring, E.G. A History of Experimental Psychology[M]. New York: Century, 1929. Also, Crafts, L.W. & T.C.Schneirla & E.E.Robinson & R.W.Gilbert, Recent Experiments in Psychology[M]. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1938.

16. Lewin, K. Principles of Topological Psychology[M]. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1936.

17. Brown, J.F. & A.C.Voth, “The path of seen movement as a function of the vector field,” American Journal of Psychology[J]. Vol.49(1937):543—563.

18. Schneirla, T.C. “Studies on the army ant behavior pattern. Nomadism in the swarm raider ECITON BURCHELLI,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society[J]. Vol.87(1944):438—457, with excellent bibliography.

19. Zipf, G.K. “Relative frequency as a determinant of phonetic change,” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology[J]. Vol.40(1929):1—95.

20. Mowrer O.H. & H.M.Jones, “Extinction and behavior variability as function of effortfulness of task,” Journal of Experimental Psychology[J]. Vol.33(1943):369—386.

21. DeCamp, J.E. “Relative distance as a factor in the white rat's selection of a path,” Psychobiology[J]. Vol.2(1920):245—253.

第二章

1. Zipf, G.K. The Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1935, Chap.1. Zipf, G.K. “On the economical arrangement of tools; the harmonic series and the properties of space,” Psychological Record[J]. Vol.4(1940):147—159.

2. The literature on the topic of meaning is enormous. For extensive bibliography primarily from the viewpoint of linguistics, cf. Bloomfield, L.Language[M]. New York: Henry Holt, 1933; also, Reichling, Anton. Het Woord[M]. Nijmegen: J.J.Berkhout, 1935. For bibliography for more general psychological and semantic angles, cf. Hayakawa, S.I. Language in Action[M]. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1941; Morris, Charles. Signs, Language and Behavior[M]. New York: Prentice Hall, 1946(in this book Dr.Morris himself makes important contributions). For further systematic treatments, cf. Korzybski, Alfred. Science and Sanity(2 ed.)[M]. Lancaster, Pa.: Science Press Printing Co., 1941; aslo, Carnap, Rudolf. Introduction to Semantics[M]. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1942. For our own systematic Treatment of meaning, cf. Chaps. 3, 5—8.

3. Hanley, M.L. Word Index to James Joyce's Ulysses[M]. Madison, Wis., 1937(statistical tabulation by M.Joos). Historically considered, Joyce's Ulysses was selected for analysis in the attempt to show that the harmonic distribution would not be found in samples of this size[cf.Joos, M. review of Zipf, Psycho-Biology of Language, in Language[J]. Vol.12(1936):196—210; cf. my reply, with quotations from Stone, M.H. “Statistical methods and dynamic philology,” Language[J]. Vol.13(1937):60—70]. Dr.Joos's Ulysses data provided the most clear-cut example of a harmonic distribution in speech of which I know.

4. The first person(to my knowledge)to note the hyperbolic nature of the frequency of word usage was the French stenographer, J.B.Estoup who made statistical studies of French, cf. his Games Stenographiques[M]. Paris, 4 ed., 1916(I have not seen his earlier editions). See also, Dewey, Godfrey. Relative Frequency of English Speech Sounds[M]. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1923; also Condon, E.V. “Statistics of Vocabulary,” Science[J]. Vol.67(1928), p.300; also Zipf, Psycho-Biology[M]. etc., op.cit.

5. Eldridge, R.C. Six Thousand Common English Words[M]. Buffalo: The Clement Press, 1911; graphed Zipf, Psycho-Biology[M]. op.cit., p.44.

6. Thorndike, E.L. A Teacher's Word Book of 20 000 Words[M]. New York: Teachers College, 1932.

7. The results of the Lorge semantic count for the words in question were taken from Thorndike, E.L. The Thorndike-Century Senior Dictionary[M]. New York: Appleton-Century, 1941. For other possible source material, cf. Eaton, Helen S. Semantic Frequency List for English, French, German, and Spanish[M]. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1940.

8. Originally published, Zipf, G.K. “The meaning-frequency relationship of words,” Journal of General Psychology[J]. Vol.33(1945):251—256. My students who helped with the tabulation were, the Misses E.L.Goucher, L.Hill, R.Hubbard, E.Kleinschmidt, V.T.Spang, E.Yphantis, and the Mssrs. R.L.Borden, L.De Sanctis, T.A.Lehrer, M.Seifert, A.A.Sirna, P.H.Smith, Jr.G.M.Sokol and M.Spotnitz.

9. In the present case, as will be discussed again in detail in our following chapter, we have adopted an operational definition of meaning(i.e., we have counted the different meanings in a dictionary). Cf. Bridgman, P.W. “Operational Analysis,” Philosophy of Science[J]. Vol.5(1938):114—131; also, his Logic of Modern Physics[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1927. In Chaps.5 and 7 we shall approach the problem of meanings from a different angle.

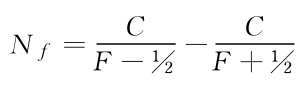

10. Argument presented in Zipf, G.K. “Homogeneity and heterogeneity in language,” Psychological Record[J]. Vol.2(1938):347—367. The argument was essentially as follows: Let N, equal the number of different words of integral frequency, F. Assume that this includes all words, the r×f=C distribution, that lie between F+1/2 and F-1/2. Thence

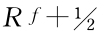

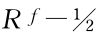

(i.e., the subtraction of the rank,  from the

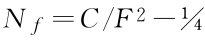

from the  . Simplifying we have

. Simplifying we have  ). For the more general case in which the rank-frequency distribution has other slopes than -1.00, cf. the ingenious analysis of Mr.Joos, Language[J]. Vol.12(1936):196—210, in which Joos shows that the exponent of f of a rank-frequency distribution is approximately larger by 1.00 than the exponent of F of the number-frequency distribution.

). For the more general case in which the rank-frequency distribution has other slopes than -1.00, cf. the ingenious analysis of Mr.Joos, Language[J]. Vol.12(1936):196—210, in which Joos shows that the exponent of f of a rank-frequency distribution is approximately larger by 1.00 than the exponent of F of the number-frequency distribution.

11. Zipf, G.K. Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language[M]. Cambridge. Harvard Univ. Press, 1932, for the frequency lists for Plautus and for Pekingese Chinese.

12. Prendergast, G.L. A Complete Concordance to the Iliad of Homer[M]. London: Longmans Green, 1875.

13. Zipf, G.K. “Repetition of words, time perspective, and semantic balance,” Journal of General Psychology[J]. Vol.32(1945):127—148.

14. The argument of the bell analogy and its related tool analogy will be found, ibid.

15. Laeber,F.K.Beowulf and the Fight at Finnsburg[M]. Boston: D.C.Heath, 1922.

16. Op.cit.

17. Sample from Sapir, E. Nootka Texts[M]. Philadephia(Linguistic Society of American): Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1939. Vide infra.

第三章

1. Zipf, G.K. “On the economical arrangement of tools; the harmonic series and the properties of space,” Psychological Record[J]. Vol.4(1940):147—159; “The repetition of words, time perspective, and semantic balance,” Journal of General Psychology[J]. Vol.32(1945):127—148.

2. This situation, when translated, say, in terms of the principle of least action in physics, suggests an interesting philosophical problem that relates to choice. Thus if a mass, M, must move by least action from a point, p0, at a time, t0, to a point, p1, at a time, t1, and if two different courses of least action are available, what then governs the “choice?”

3. As we pointed out in Chap.1, the work of planning, or of designing, is always to be reckoned to the total cost in work of performing the job. This prevents a person from endlessly elaborating the details of his problem.

4. Professor Walsh, J.L.has pointed out that a typesetter is an excellent example of the tool analogy in practical life, particularly if he is setting Chinese character(or ideographs)in which one piece of type represents a whole “word”(actually a morpheme, vide infra). The most frequently used characters will be located nearest to the typesetter, etc.

5. Presented, Zipf, Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit., Chap.2.

6. Ibid.; also Zipf, Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language[M]. op.cit.

7. A virtually complete bibliography of the frequency lists of words(up to 1940)can be found in Fries, Charles C. and A.Aileen Traver, English Word Lists[M]. Washington, D.C.; American Council on Education, 1940.

8. Thorndike, E.L. Studies in the Psychology of Language(Archives of Psychology, No.231)[M]. New York, 1938:67.

9. Zipf, Psycho-Biology of Language, op.cit.[M]. Chaps.2, 5 and 6.

10. Essentially an operational definition to use P.W.Bridgman's term, op.cit. supra Chap.2, reference 9.

11. An excellent discussion of the problem of classification of speech entities is contained in the article on “Alphabet,” Encyclopaedia Brirranica, 14th ed.[M]. See also, Leonard Bloomfield, Language[M]. New York: Holt, 1933.

12. Ibid., Chaps. 13 and 14 which contain an excellent discussion of the entire problem by one of America's outstanding scholars in the field.

13. Sapir, E. Nootka Texts[M]. Philadelphia(Linguistic Society of America): Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1939.

14. Bloomfield, Leonard. Plains Cree Texts[M]. New York: Stechert, 1934.

15. Cf. Chap.2, reference 10, supra, for further discussion of this point with bibliography.

16. Deloria, Ella Dakota Texts[M]. New York: Stechert, 1932.

17. Kaeding, F.W. Häufigkeitswörterbuch der deutschen Sprache[M]. Berlin, 1898.

18. I am grateful to my friend, Professor Chao, R.Y. for his kindness in calling this book to my attention and in procuring a copy for me.

19. Stritberg, Wilhelm. Die Gotische Bibel, 2 revised ed.[M]. Heidelberg; Carl Winter, 1919.

20. Zipf, Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency[M]. op.cit; Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit.

21. For a bibliography of texts and editions of Old and Middle English with a discussion of the history of English, cf. Henry Cecil. Wyld, A Short History of English[M]. New York: E.P.Dutton, 1937.

22. Zipf, Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit, pp.172—176.

23. For an operational discussion of the phoneme, cf. Bloomfield, Language[M]. op.cit., Chap.5; criticized in part by Zipf, G.K. “The psychology of language,” in The Encyclopaedia of Psychology[M]. New York: Philosophical Library, 1946:332f.; Stetson, R.H. Bases of Phonology[M]. Oberlin: Oberlin College, 1945 is the most comprehensive treatment from the philosophical and psychological angles.

24. Zipf, Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language[M]. op.cit.

25. Zipf, Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit, pp.68—73.

26. The data of Table 3-3 have been previously published and discussed in one or more of the following publications: Zipf, G.K. “Relative Frequency as a determinant of phonetic change”; Harvard Studies in Classical Philology[J]. Vol.40(1929):1—95; Psycho-Biology of Language, op.cit.[M]. pp.73—76; Zipf G.K. & F.M.Rogers, “Phonemes and variphones in four present-day Romance languages and Classical Latin from the viewpoint of Dynamic Philology,” Archives Nèerlandaises de Phonètique Expèrimentale[J]. Vol.15(1939):111—147. For the frequencies of voiceless dentals in several German dialects not included in Table 3-3, cf. Zipf, G.K. “Phonometry, Phonology, and Dynamic Philology: an attempted synthesis,” American Speech[J]. Vol.13(1938):283—284.

27. Hudgins, C.V. & R.H.Stetson, “Voicing of consonants by depression of larynx,” Archives Neerlandaises de Phonetique Expèrimentale[J]. Vol.11(1935):1—28.

28. The sources of the data of Table 3-4 are the same as those for Table 3-3, as given in reference 26. supra.

29. Elaborated in detail, Zipf, Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit., pp.81—129.

30. Ibid.

31. Zipf, “Phonometry, Phonology and Dynamic Philology: ...”[M]. op.cit., p.282, fn. 27.

32. Bloomfield, Language[M]. op.cit., p.81.

33. Zwirner, E. and K.Zwirner, “Phonometrischer Beitrag zur Frage der neuhochdeutschen Quantität,”Archivfiir vergleichende Phonetik[J]. Vol.1(1937):96—113. Further bibliography on the Drs.Zwirners' important work is given in Zipf, “Phonometry, Phonology and Dynamic Philology: ...” [M]. op.cit., passim.

34. Lehmann, W.P. and R.M.S.Heffner, “Notes on the lengths of vowels,”American Speech[J]. Vol.18(1943):208—215. Here also bibliographical material on their earlier publications on the topic.

35. Hudgins, C.V. and F.C.Numbers, “An investigation of the intelligibility of the speech of the deaf,”Genetic Psychology Monographs[J]. Vol.25(1942):289—392; cf. p.363 f.

36. Menzerath, P. and A.de Lacerda, Koartikulation, Steuerung und Lautabgrenzung[M]. Berlin and Bonn: Ferd. Dummlers Verlag, 1933.

37. As the phonemic distinctions are gradually eliminated from a sample of speech, the resulting rank-frequency distributions of words seem to remain linear, with increasing slope, as judged by a preliminary study made by the present author.

38. Taken from Thompson, D.W. On Growth and Form[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1943:338—339.

39. Zipf, G.K. “Cultural chronological strata in speech,”Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology[J]. Vol.41(1946):351—355.

40. Feist, Sigmund. Vergleichendes Wörterbuch der gotischen Sprache[M]. Leiden: Brill, 1939.

41. Zipf, G.K. “Prehistoric ‘Cultural Strata’ in the evolution of Germanic: the case of Gothic,” Modern Language Notes[J]. Vol.62(1947):522—530.

42. Zipf, G.K. “Homogeneity and heterogenerity in language,”Psychological Record[J]. Vol.2(1938):347—367.

43. Zipf, G.K. Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language[M]. op.cit.

44. For the summation of the generalized harmonic series see the approximate formulas published in Stewart, J.Q. “Empirical mathematical rule concerning the distribution and equilibrium of population,” Geographical Review[J]. Vol.37(1947):464, in which reference is made to Glaisher, J.W.L. “The constants that occur in certain summations of Bernoulli's series,” Pro. London Math. Soc.[J]. Vol.4(1871):48—56.

第四章

1. For an excellent up-to-date comprehensive treatise, cf. Carmichael, Leonard. Editor, Manual of Child Psychology[J]. New York: Wiley, 1946; for the particular interests of the present chapter, cf. McCarthy, Dorothea. “Language development of children,” ibid, Chap.10(also contains an extensive bibliography). See also, Stoddard, G.D. and B.L.Wellman, Child Psychology[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1934.

2. Uhrbrock, R.S. “The vocabulary of a five-year old,”Educational Research Bulletin[J]. Vol.14.(1935):85f.; also his “Words most frequently used by a five-year old girl,” Journal of Educational Psychology[J]. Vol.27(1936):55—158. Cf.Zipf, G.L. “Children's Speech,” Science[J]. Vol.96(1942):344—345.

3. For an equation that describes these differences in slope the result from differences in sample size, under the assumption that the optimum sample is harmonically seriated(and also, I think, that the interval frequency equation of Chapter 2 applies), cf.Carrol, J.B. “Diversity of vocabulary and the harmonic series law of word frequency distribution,”Psychological Record[J]. Vol.2(1938):379—386.

4. Fisher, M.S. Language Patterns of Preschool Children[R].(Child Development Monographs, No.15)New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1934.

5. Zipf, G.K. “Observations of the possible effect of mental age upon the frequency distribution of words from the viewpoint of dynamic philology,”Journal of Psychology[J]. Vol.4(1937):239—244, in which is also reported my statistical analysis of the speech-sample contained in Haggerty, L.C. “What a two-and-one-half-year-old child said in one day,” Journal of Genetic Psychology[J]. Vol.37(1930):75—101.

6. Hilgard, Ernest R. Theories of Learning[M]. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1948.

7. Thorndike, E.L. “The origin of language,” Science[J]. Vol.98(1943):1—6. This article contains a discussion of various of the chief theories(or speculations)about the “origin of speech.”

8. M.S.Fisher, Language Patterns of Preschool Children, op.cit.; also Dorothea McCarthy, “Language development of children,” op.cit., reference 1 supra.

第五章

1. This will be an example of our indebtedness to the thinking and terminology of “classical” or “orthodox” economics as acknowledged in Chap.1, Section V. By the same token the argument of Chap.5, Section I, seq., as well as that of Chaps. 9, 10, 11, and 12 may be viewed as an elaboration of economic theory, if one will. We mention these considerations lest we otherwise be accused of “ignoring economics.”

2. We described this difference in Chap.1, Section IV.

3. This relativism between tools and jobs was discussed in Chap.1, Section IV.

4. There is a tendency for interest rates to increase with the length of the term, even with apparently equal security(e.g., U.S.government notes). This tendency is germane to our argument.

5. For an interesting description of the problem of the gibbon ape in wandering through the tree-tops, cf. Lull, R.S. Organic Evolution[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1927, p.649.

6. The entire history of the field of sensation has been brilliantly presented in Boring, E.G. Sensation and Perception in the History of Experimental Psychology[M]. New York: Appleton-Century, 1942.

7. For the physiology of homeostasis cf. Cannon,W.B. Bodily Changes in Pain Hunger, Fear and Rage[M]. New York: Appleton, 1929; also his Wisdom of the Body[M]. New York: Norton, 1939. See also, Hoskins, R.G. Endocrinology; the Glands and their Functions[M]. New York: Norton, 1941.

8. Op.cit., fn.7 supra.

9. The data presented here will be found in Zipf, G.K. “Some psychological determinants of the structure of publications,”American Journal of Psychology[J]. Vol.57(1945):425—442.

10. Previously presented ibid.

11. These standard deviations were kindly calculated by Mr. Schleifer, M.J. ibid.

12. Previously presented ibid.

13. Previously presented ibid.

14. General Education in a Free Society; Report of the Harvard Committee[R]. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1945.

15. This question of news is again examined from the social angle in Chap.9.

16. Cf. Chap.11 for data on speeches of a play with brief discussion of the problem of the scenes of a moving picture.

17. Hence the n number of the increasing articulation and integration of a class(as well as the n number of classes) will always be d positive integral number.

18. For a discussion of the increasing articulation and integration of a person's semantic system with reference to emotion, cf. Zipf, G.K. Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit., Chaps.5 and 6.

19. For a discussion of abbreviation as the basic dimension of speech, cf, ibid. pp.288—288.

20. Not to be misunderstood, we are showing the need of living process for a constant clock in an atom. We have not shown that electronic action is the clock, but have merely suggested that it may be.

21. For a discussion of genes of meaning as the smallest units of classificatory action, cf. Zipf, Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. pp.287, 299—303.

22. In this connection one is reminded of Henri Le Chatelier's famous principle first established in the field of thermodynamics and subsequently extended in scope(i. e., any system tends to alter itself in order to neutralize the effects of an impingement upon it). The principle also seems to operate in the social field(cf. Part 2).

23. For this view of emotion, and of pleasure and pain, cf. Zipf, G.K. Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language[M]. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1932, passim.; also, Psycho-Biology of Language, op.cit., pp.191, 207—215.

24. This concept seems to be intrinsic in the guilt complex of the Freudian school according to which persons confess to crimes which they never committed for the sake of an official punishment that will satisfy their unconscious feelings of guilt that arise from a desire to commit crimes against society(cf. discussion of a mother fixation in Chapter 7 infra). For a comprehensive account of psychoanalytic theories and concepts, cf. Brown,J.F. The Psychodynamics of Abnormal Behavior[M]. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1940; also, Sears, R.R. “Survey of objective studies of psychoanalytic concepts”[R].(Bulletin of the Social Science Research Council, No.51)New York: 1943. Also, Hunt(editor), J.M. Personality and the Behavior Disorders[M]. New York: Ronald, 1944; also, Dr.Hunt's excellent “Experimental Psychoanalysis,” in Encyclopedia of Psychology[M]. New York: Philosophical Library, 1946:140—156.

25. For concepts and experimental data of Gestalt psychology, cf. Hartmann, G.W. Gestalt Psychology[M]. New York: Ronald, 1935; Kohler, W. Gestalt Psychology[M]. New York: Liverright, 1928; Koffka, K. Principles of Topological Psychology[M]. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1936; also, Lewin, K. A Dynamic Theory of Personality[M]. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1935.

26. Cf. Miller, J.G. Unconsciousness[M]. New York: Wiley, 1942, for an excellent critical discussion of the various theories about consciousness and unconsciousness, with important contribution by Dr.Miller himself.

27. For the view of physiological activity as a traffic system, cf. Child, C.M. Physiological Foundations of Behavior[M]. New York: Holt, 1924, Chap.17. Cf. Chps. 9—10 infra for the dynamics of a social traffic system, and Chap.11 for a discussion of a hierarchy of controls.

28. The effect of the “cumulative force of chance in speech” discussed in Zipf, Psycho-Biology [M]. op.cit., 200 f.

29. A great deal of aging may be governed by cultural conventions. Thus we tell a child(generally incorrectly)“that is not the way an 8-year-old boy behaves.” People tend to behave at a given age as they are supposed to: at forty, we behave and feel forty; at fifty, fifty; at three score years and ten we tend to act as respectable persons are supposed to act in anticipation of death. For a discussion of cultural roles cf. Chaps.7 and 8.

30. On the other hand, the persons of greater intelligence tend to be more successful in the sense of receiving greater incomes and positions of higher status, and therefore can buy themselves more favorable environments(cf. Chap.11 infra).

31. If a portion of the brain is removed, the functions of the removed part are frequently taken over by what is left of the brain.

第六章

1. For a discussion of this transformation of energy, cf. Lotka, A.J. Elements of Physical Biology[M]. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1925, Chaps.24—28; also, Thompson, D.W. On Growth and Form[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1943, Chaps.1—6, and passim.

2. For a discussion of “the ego as a coordinate reference frame,” cf. Lotka, A.J. Elements of Physical Biology[M]. op.cit., pp.372—374.

3. The problem of the length of an organism's life is discussed, Thompson, D.W. On Growth and Form[M]. op.cit., passim.

4. It is by no means true that all physicists ignore the problem of life. In this connection see the brilliant study of Schrödinger, E. What Is Life?[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1945. This study is particularly interesting for our purpose, not only because an eminent physicist brings his great knowledge to bear on the topic, but more particularly because he points out(p.21)that chromosome structures are both “law code(sic)and executive power-or, to use another simile, they are architect's plan(sic)and builder's craft-in one.” This concept of “code” and “plan” ties in with our own belief that the artisan of our tool analogy(Chaps.3 and 5)is present in the tiniest minutiae of living behavior and that all living action is classificatory throughout in terms of a plan of the whole organism in question(cf. Zipf, G.K. The Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit., Chap.6, and pp.299—303). Dr.Schrödinger view the organism in the light of known physical laws and finds the known physical laws inadequate(e.g., “For it is in relation to the statistical point of view that the structure of the vital parts of living organisms differs so entirely from that of any piece of matter that we physicists and chemists have ever handled physically in our laboratories or mentally at our writing desks,” p.3). We for our part view organic action against the background of the speech process and postulate an identity point in order to keep an organism from collapsing. Is this identity point somehow a supervisory control? If existent, does it imply a further property of matter and if so, what?(cf. Schrödinger's Chaps.6 and 7). Is there some sort of “vital” factor in all matter that manifests itself organically on the surfaces of very large masses? If so, the so-called “vitalists”(a school of psychologists)have scarcely shown it. There is little doubt that organic process, in its capacity as sheer organic process, is itself orderly, and, for all we know, quite as orderly as inanimate physical processes. It may be that the principles of organization of human speech are the laws of organization of the organism. Perhaps the hypothesis that the entire universe is alive may be helpful in studying the dynamics of animate phenomena within the framework of presumably inanimate phenomena. For discussion of consciousness, cf. Lotka, A.J. Elements of Physical Biology[M]. op.cit., Chaps.29—32, in which there are extensive references to earlier literature.

5. Malthus, T.R. An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the Future Improvement of Society[D]. London: J.Johnson, 1798; the final revision, An Essay on the Principle of Population, or, A View of its Past and Present Effects[D]. London: J.Murray, 1817.

6. The growth rate slackens long before the hunger line is reached. For bibliography on the studies of Raymond Pearl and others, as well as for critical discussion, cf. Thompson, D.W. On Growth and Form[M]. op.cit., 155 f.

7. The absurdity and the danger of the dichotomy between self and environment, as well as the topic of mind as a scientific fiction, are interestingly discussed in Lotka, A.J. Elements of Physical Biology[M]. op.cit., pp.374—375. In Chap.7 we shall assume that mind is a scientific fiction. In order to emphasize the viewpoint that living process is a manner of organizing the earth's surface, and that a person is merely a part of the entire universe, there may be a certain didactic value in suggesting speculatively that the N number of organisms that are alive on the surface of a large mass varies directly with the mass. This speculation may fit in with certain observations of astronomy(cf. Zipf, G.K. “On the economical arrangement of tools; the harmonic series and the properties of space,” The Psychological Record[J]. Vol.4, 1940:159), as will be elaborated subsequently in greater detail in connection with the generalized harmonic series.

8. For a discussion of food chains and cycles cf. Lotka, A.J. Elements of Physical Biology[M]. op.cit., p.136f., pp.176—184.

9. Volterra, V. Fluctuations dans la little pour la vie[M]. Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1938; Kostitsin, V.A. Biologie Mathematique[M]. Paris: Librairie Armand Colin, 1937; Lotka, A.J. Elements of Physical Biology[M]. op.cit.

10. If we substitute the term, frequency of occurrence, for area in this sentence we have a statement that applies mutatis mutandis to words in the stream of speech.

11. For his most recent statement, with data, cf. Willis, J.C. The Course of Evolution[M]. Cambridge, England: The University Press, 1940. See also his Age and Area[M]. Cambridge, England: The University Press, 1922.

12. Ibid.

13. It may be that the first explanation of the dynamics of any phylogenetic mutation was that of human phonetic change(in 1929). According to the important and original observations of Herbert Friedmann, different species of birds in similar environmental situations seem to develop similar modes of behavior, e.g., colorings, nesting habits, etc. Cf. Friedmann, H. “Ecological counterparts in birds,”The Scientific Monthly[J]. Vol.63, 1946:395—398. [“The number of possible permutations and combinations of the different colors and patterns(spots, bars, stripes, etc.)found in birds is far greater than the number of kinds of birds. It is, therefore, interesting, and probably significant, that there should be as many instances of convergence among unrelated groups as there are. It is all the more intriguing when we found that these similarities in appearance are so often correlated with equally marked similarities in habit,” ibid, p.398]

14. Discussed with literature in Thompson, D.W. On Growth and Form[M]. op.cit., p.155f.

15. There is no single official Freudian Theory but rather a more or less well recognized body of doctrine that includes conflicting views. These are critically discussed in Brown, J.F. The Psychodynamics of Abnormal Behavior[M]. op.cit., passim. In our discussion of Freudian Theory(as we understand it)we shall refer to the general theories without specific reference.

16. The topic of rate of growth is exhaustively treated by Thompson, D.W. On Growth and Form[M]. op.cit., Chap.3, 78—285.

17. The view of phonemes as norms may be of general applicability to biosocial process, cf.Zipf, G.K. The Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit., Chap.3. There are abundant observations of the “normal curve” that attest to the frequency of this type of distribution and yet which, for the most part, remain unrationalized.

18. Enunciated by Ernst Haeckel in his Generelle Morphologie[J]. Vol.2. 1866. It is in sum “ontogeny repeats phylogeny.” Copious illustrations in Lull, R.S. Organic Evolution[M]. op.cit., Chap.14 and passim.

第七章

1. Chapple, E.D. and C.S.Coon, Principles of Anthropology[M]. New York: Holt, 1942, Chap.12, 13, and bibliography. See also relevant articles in The Encyclopaedia of the Social Science[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1931.

2. For brief bibliography on Freudian and general psychoanalytic concepts cf. reference number 24 in Chap.5.

3. Malinowski, B. Sex and Repression in Savage Society[M]. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1927; The Father in Primitive Society[M]. New York; Norton, 1927; The sexual Life of Savage in Northwestern Melanasia[M]. 3d, ed., 2 Vols., London: Routledge, 1932. Boas, F. The Mind of Primitive Man[M]. Revised ed., New York: Macmillan, 1938.

4. The terms, fixation, mother fixation, mother's image, are borrowed from current psychiatric terminology.

5. For an excellent discussion with a very complete bibliography, cf. Seward, G.H. Sex and the Social Disorder[M]. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1936. For empiric data on human male sexual behavior, with extensive bibliography, cf. Kinsey, A.C. & W.B.Pomeroy & C.E.Martin, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male[M]. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1948; see particularly Chap.21(“Homosexual Outlet”)and Fig.161, p.638, for a theoretical diagram of heterosexual-homosexual frequency distribution. These three scientists, on the basis of their extensive observations, arrived inductively at their concept of heterosexual-homosexual balance at which we arrived on the whole deductively from our Principle of Least Effort, as tested by the male-female birth ratios; hence, the studies complement each other, with ours confirming theirs and attempting to rationalize the balance in question. We mention this in this note because the manuscript of our text was essentially complete before the publications of the book by Dr.Kinsey and associates. The speculative concept of a universal sexual bipolarity is quite old.

6. Reported in Henry, G.W. Sex Variants[M]. 2 Vols., New York: Hoeber, 1941. This study contains a wide selection of case histories with physical measurements.

7. For the very considerable literature on sexual hormones cf. Bibliography in Seward, G.H. Sex and the Social Order[M]. op.cit.

8. Ellis, H. Studies in the Psychology of Sex[M]. 4 vols., New York: Random House, 1936.

9. For the general Freudian views on oral and anal eroticism, cf. Brown, J.F. The Psychodynamics of Abnormal Behavior[M]. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1940: 186—193. For the general clinical background, cf. Noyes, A.P. Modern Clinical Psychiatry[M]. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1935.

10. For his earliest statement of his theory, cf. Meillet, A. “Le genre feminin dans les langues indoeuropeennes,” Journal de psychologie normale et pathologique[J]. Vol.20, 1923:943—944. Equally important is the ensuing discussion by M.Mauss, ibid., 944—947, with references to J.G.Frazer. Dr.Meillet elaborated his theory further in a lecture delivered at Harvard University in 1930.

11. Brugmann, Karl. Kurze vergleichende Grrammatik der Indogermanischen Sprachen[M]. Strassburg: Trubner, 1902—1904. For a different view, cf. Hirt, H. Handbuch des Urgermanischen[M]. Teil Ⅱ(Stammbildungs und Flexionslehre), Heidelberg: Winter, 1932:15ff.

12. Sir Frazer, J.G. The Golden Bough[J]. 12 Vols., 3rd ed., New York: Macmillan, 1935; also abridged ed., ibid., 1922.

13. For mathematics ct. article, “Groups, theory of,” in Encyclopaedia Britannica[M]. 11ed., Vol.12, 626—636.

14. Wertherimer, M. Drei Abhandlungen zur Gestalt Theorie[M]. Erlangen: Philosoph. Akademie, 1924(new ed. 1925).

15. The term, superego, is borrowed from Freudian theory, for a discussion of which cf.Brown, J.F. The Psychodynamics of Abnormal Behavior[M]. op.cit., pp.162—167(p.167 “... all behavior is economical ... conflict situation are resolved in accordance with the least expenditure of energy possible in one existing total situation. This proposition cannot at the present time be proved but it is an invaluable working hypothesis for psychology. Through accepting it we are able to see order in behaviors which were previously thought of as accidental and chaotic”).

16. The structure of a code of social correlations will be discussed in considerable detail with empiric data in Part 2, Chaps. 9, 11, and 12. For an excellent discussion of culture, cf. B.Malinowski's article on “Culture” in The Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences[M]. op.cit., Vol.4, p.621 f., also, his A Scientific Theory of Culture, and other Essays[M]. Chapel Hill: Univ. of No. Carolina Press, 1994.

17. For a penetrating discussion of the sympathetic nervous system, cf. Cannon, W.B. The Wisdom of the Body[M]. New York: Norton, 1932. Also Dent, J.Y. The Human Machine[M]. New York: Knopf, 1937; Clendenning, L. The Human Body[M]. New York: Knopf 1927. See also Whitehorn, John C. “Physiological changes in emotional states,” Research Publications of the Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease[C]. Vol.19, 1939: 256—270.

18. See reference no.15 above.

19. Closely associated with this belief in the capacity of a word to create is the adage, “Speak of the devil and he is bound to appear,” As philologists long ago pointed out, in olden days the people who lived in a land where there were bears tended not to use the name, bear, lest one appear; instead they referred to him, say, as “the brown one.” The Greeks had a highly flattering(and hence placating)name for the dreaded Furies. Closely related is the phenomenon of inverse semanticism, e.g., “the hog is well named since he looks and acts like a hog.”

20. I am indebted to Dr.J.C. Whitehorn for his concept. For an actual case history, cf. Whitehorn, J.C. “The material in the hands of the biochemist,” American Journal of Psychiatry[J]. Vol.92, 1985:318—319. For a discussion of the relation between psychiatry and culture and sentiments, cg. Whitehorn, J.C. “Psychiatry as a basic medical science,” The Connecticut State Medical Journal[J]. Vol.6 No.9, 1942:693 f.

21. In this connection, cf. Henry Sturt's article on “Induction,” The Encyclopaedia Britannica[M]. 11th ed.

22. Zipf, G.K. The Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit., 304—309 connection of social reality in speech.

23. Strecker, E.A. and F.G.Ebaugh, “Dementia Praecox(Schizophrenic reaction types)” in Gardner Murphy, ed., An Outline of Abnormal Psychology[M]. New York: Modern Library, 1929:71—101(graph on age of admissions of 200 schizophrenic patients in Phila. Gen'l Hospital on p.72). Reprinted from their Practical Clinical Psychiatry from their Practical Clinical Psychiatry, 2nd ed., Philadelphia: Blakiston(3rd ed.), 1931.

24. Whitehorn, J.C. and G.K.Zipf, “Schizophrenic language,” Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry[J]. Vol.49, 1943:831—851. For his views on autism and schizophrenia, the writer is deeply indebted to the thinking of Dr.Whitehorn.

25. Cameron, N. “Schizophrenic thinking in a problem-solving situation,” Journal of Mental Science[J]. Vol.85, 1939:1012—1035. Subsequently, Dr.Cameron has elaborated his theory in his The Psychiatry of Behavior Disorder[M]. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1947.

26. Zipf, G.K. The Psycho-Biology of Language[M]. op.cit. 267f. for a discussion of a word as a name of a frequently used category of experience.

27. Kretschmer, E. Physique and Character[M].(translated by W.J.Sprott from the 2nd revised German edition), New York: Harcourt Brace, 1925.

28. In this connection, cf. Birkhoff, G.and S.Maclane. A Survey of Modern Algebra[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1941.

29. The constructs of Chaps. 9 and 11 may conceivably serve as useful analogues of the organization of a person's mind.

第八章

1. Wendell, Barrett. introduced these terms, also charm, force, elegance in his Lowell Institute lectures on “English Composition”(cf. Wendell, B. English Composition[R]; Eight Lectures given at the Lowell Institute[R]. New York: Scribner's, 1891, and subsequent printings). In the opinion of a friend, many successful plays seem to have none of Wendell's desired characteristics.

2. For extensive statistical studies of music, cf. Schillinger, J. The Schillinger System of Musical Composition[M]. 2 Vols., New York: C.Fischer, Inc., 1946.

3. de Grazia, S. “Shostakovich's Seventh Symphony; reactivity-speed and adaptiveness in musical symbols,” Psychiatry: Journal of the Biology and Pathology of Interpersonal Relations[J]. Vol.6, 1948:117—122.

4. Furlan, L.V. Das Harmoniegesetz der Statistik[M]. Basel: Verlag fur Recht und Gesellschaft, 1946. Cf. Kull, W. “Das Harmoniegesetz der Statistik: eine Buchbesprechung,” Zeitschrift fur Volkswirtschaft und Statistik[J]. Vol.82, 1946:414—433.

5. Benford, B. “The law of anomalous numbers,” Proceeding of the American Philosophical Society[J]. Vol.78, 1938:551—572.

第九章

1. This lemma is presented in somewhat greater detail in Zipf, G.K. National Unity and Disunity [M]. Bloomington, Ind.; Principia Press, 1941:100—135; also “The generalized harmonic series as a fundamental principle of social organization,” Psychological Record[J]. Vol.4, 1940:43.

2. Argument presented in Zipf, G.K. “The unity of nature, least-action, and natural social science,” Sociometry[J]. Vol.5, 194:48—62.

3. From this it follows that an inventor can be “ahead of his time.”

4. Zipf, G.K. “On the economical arrangement of tools; the harmonic series and the properties of space,” Psychological Record[J]. Vol.4, 1940:147—159.

5. Zipf, G.K. “The hypothesis of the ‘Minimum Equation’ as a unifying social principle: with attempted synthesis,” American Sociological Review[J]. Vol.12, 1947:627—650.

6. This concept will apply to the locations of persons of tabooed variations in human sexual behavior whose sexual demands and services are of an unusual nature. Theoretically, the percentage of such persons in a P city will tend to increase with P, and so, too, the m diversity of their variant behavior.

7. Later, in this chapter, and in subsequent chapters, we shall note repeatedly how these “difficulties” tend to increase according to the square of the n items. In general a population of C size, with each member interacting with every other member, will have C2 interactions(treated in Zipf, G.K. “On Dr.Miller's Contribution, etc.,”[J]. op.cit., infra, no.9.)

8. Auerbach, Felix. “Das Gesetz der Bevolkerungskonzentration,” Petermanns Mitteilungen[M]. 1913:74 f.; Lotka, A.J. Elements of Physical Biology[M]. Baltiomore: Williams and Wilkins, 1925:306 f.; Goodrich, E.P. “The statistical relationship between population and the city plan,” American Journal of Sociology[J]. Vol.20, 1926:123—128; Gibrat, R. Les Inegalites Ecnomiques[M]. Paris: Recueil Sirey, 1931:Fig.XI, p.280; Zipf, G.K. National Unity and Disunity[M]. Bloomington, Ind.: Principia Press, 1941, Chaps.1—4.

9. Reported in Zipf, G.K. “On Dr.Miller's contribution to the(P1P2)/D hypothesis,” American Journal of Psychology[J]. Vol.60, April, 1947:286, fn.; also his “The hypothesis of the ‘Minimum Equation’ as a unifying social principle: with attempted synthesis,” American Sociological Review[J]. Vol.12, 1947:627—650. My student, Mr.Robert M.Ritter, helped materially in the tabulation of the data of Fig.9-2.

10. Ibid.

11. In our hypothesis as developed in Sections I and II supra on the boundaries of all cities we deduced theoretically that the actual densities at the boundaries of all cities would be about the same and that, therefore, there was a natural limit to a city's area. Dr.Stewart, J.Q. in his “Suggested Principles of ‘Social Physics’,” Science[J]. Vol.106, Aug.29, 1947:179—180, reports on the basis of his important studies of population densities(p.180): “There is strong evidence for the following standard internal pattern, as a first approximation: The normal city, regardless of size, has roughly the same density of population at its edges, averaging there about 3 people per acre or 2 000 per square mile.” This confirms our education empirically.

12. Reported in Zipf, G.K. “The frequency and diversity of business establishments and personal occupations: a study of social stereotypes and cultural roles,” Journal of Psychology[J]. Vol.24, 1947:139—148; also Zipf, “The hypothesis of the ‘Minimum Equation’ as a unifying social principle,” etc., op.cit. My students, as listed below, helped materially in the tabulation of the data: Messrs. J.P.Boland, D.D.Bourland, Jr., A.Fellows, R.V.Johnson, M.I.Liebmann, T.Macklin, D.G.Outerbridge, R.L.Perry, R.M.Ritter, J.A.Sevin, and J.D.Stanley.

13. Presented ibid.

14. Reported ibid.

15. The deduction that the constant Cp will vary directly with the P sizes of individual communities, cf. supra(also Zipf, G.K. “The frequency and diversity of business establishment and personal occupations ...” op.cit., p.144), has been confirmed empirically by my student, Mr.D.D.Bourland, Jr., on the basis of the rank frequency distribution of profession listed in the classified telephone directories of cities of varying P sizes.

16. For earlier publication see references in note no.12 supra.

17. Ibid.

18. In our discussion of occupations in Chap.6(q.v.)as an introduction to the J.C.Willis data we argued that different occupations would be distributed as the genera species data of Willis which, as we note in Fig.9-7, is the case. Since, however, there is no degradation of energy in the case of human occupations as is theoretically the case with the “food chains” of species, the distribution of “Specific” and “Generic” classes of occupations should have a slope(number-frequency relationship)that is -1/2, as is approximately the case.

19. Since this was written, my student, Mr.D.D.Bourland, Jr., has confirmed this theoretical expectation; see note 15 above. This same concept of the Cp constant for a city of P size will apply to the distribution of incomes and social status within cities of varying P sizes, as is clear in Chap.11.

20. Zipf, G.K. “The frequency and diversity of business establishments and personal occupations,” etc., op.cit.

21. Ravenstein, E.G. “The laws of migration,” Journal Royal Statistical Association[J]. Vol.48, 1885:167—235 [continued, Vol.52, 1889:241—305].

22. See Reilly, W.J.Methods for the study of retail relationships, University of Texas Bulletin[C]. No.2944, 1929. See also F.Strohkarck and K.Phelps, “The mechanics of constructing a market area map,” The Journal of Marketing[J]. Vol.12, 1948:493—496.

23. See Stewart, J.Q. “An inverse distance variation for certain social influences,” Science[J]. n. s. Vol.93, 194:89; also his “The ‘Gravitation,’ or geographical drawing power, of college,” Bulletin American Association University Professors[C]. Vol.27, 1941:70; also his “A measure of the influence of a population at a distance,” Sociometry[J]. Vol.5, 1942:63—71; also his “Empirical mathematical rules concerning the distribution and equilibrium of population,” The Geographical Review[J]. Vol.37, 1947:461—485. Very important: his “Demographic gravitation: evidence and applications,” Sociometry[J]. Vol.11, 1948: Nos.1 and 2, pp.31—57.

24. Not to be overlooked is the pioneer study by A.M.Wellington, The economic Theory of the Location of Railways, 6 ed., London: Chapman Hall, New York: J.Wiley, 1906; his final law of the increment of traffic(p.713): “The productive traffic varies as the square of the number of tributary sources of traffic.” This is elaborated with tables pp.707—718; also elaborated in reference to the individual with the result that the traffic density varies directly with the square of the population(as is to be excepted theoretically from our Sections I and II above, if every person is both the point of origin and a point of destination of a 1/C share of all m kinds of goods). Wellington argued that the density of traffic between two cities is more than inversely proportional to their interesting D distance though he did not work out the relationship more precisely as did Stewart.

25. The cities in question are virtually the same as those mentioned below in connection with Figs.9-15 and 9-16, though they are listed specially with a detailed discussion of the analysis in Zipf, G.K. “Some determination of the circulation of information,” The American Journal of Psychology[J]. Vol.59, 1946:401—421. The students in question: the Misses Isabelle Abrahams, Sally Doyle, Frances M.Eaton, Mary Johnstone, and Mrs.Jeanne H.Gwinn of Radcliffe College, and Messrs. M.E.Bovarnick, Henry D.Burnham, Hubert A.Doris, Robert D.Kemble, John Francis Keogh, Marc P.Moldawer, Frederick E.Penn, Arthur W.Perkins, Marshall G.Pratt, Paul C.Richter, John L.Turner, and Peter D.Watson.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. Stewart, J.Q. “A measure of the influence of a population at a distance,” op.cit., p.70.

30. Zipf, G.K. “The hypothesis of the ‘Minimun Equation, ...” op.cit., p.642. Also Reilly, W.J.Methods for the Study of Retail Relationship, op.cit., in which is a “law of retail gravitation” for trade areas between cities(the point of equilibrium is the population divided by the square of the distance). Subsequently studies by Converse, P.D. A Study of Retail Trade Areas is East Central Illinois[C]. University of Illinois Bulletin, Vol.41, No.7(Business Studies No.2), 1943; also his Retail Trade Areas in Illinois, ibid., Vol.43(Business Studies No.4), 1946. Also Strohkarck, F. & K. Phelps, “The mechanics of constructing a market area map,” op.cit.

31. Zipf, G.K. “The(P1P2)/D Hypothesis: the case of Railway Express,” Journal of Psychology[J]. vol.22, 1946:3—8. Also, his “The(P1P2)/D Hypothesis: on the intercity movement of persons,” American Sociological Review[J]. Vol.11, 1946:677—686.

32. These data with additional data on passenger fares paid by travelers on railways and buses are presented ibid.

33. Zipf, G.K. “Some determinants of the circulation of information,” op.cit.

34. Dr.George A.Miller has made an ingenious theoretical construct on the assumption of a random sending of messages in his “Population, distance and the circulation of information.” American Journal of Psychology[J]. Vol.60, 1947:276—284; cf. Zipf, G.K. “On Dr.Miller's Contribution”, ibid., 284—287.

35. Zipf, G.K. “Some determinants of the circulation of information,” op.cit.

36. From Paddock, R.H. & R.P.Rodgers, “Preliminary results of road-use studies,” Public Roads[J]. Vol.20, 1939:33—45, Table 8 and 9. The states were Florida, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin. I am grateful to Mr.R.E.Royall, Chief of the Division of Research Reports, Public Roads Administration, Federal Works Agency for his kindness in helping me locate this material.

37. Christaller, W. Die Zentralen Orte in Suddeutschland[R]. Jena:Fischer, 1993, Karten 1—3.

38. Ullman, E. “A theory of location for cities,” American Journal of Sociology[J]. Vol.46, 1940—1941:853—864. Also Hoover, E.M. Location Theory of the Shoe and Leather Industries[M]. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1937.

39. Stewart, J. “Empirical mathematical rules concerning the distribution and equilibrium of population,” Op.cit.

40. Stewart, J.Q. Coasts, Waves, and Weather[M]. Boston: Ginn, 1945:164 f.

41. Cf. Report of commission of Housing and Regional Planning, State of New York, Jan.11. 1926. I am grateful to professor Arthur Coleman Comey for information on this subject. There is an excellent collection of material on traffic surveys in the Harvard Library of Regional Planning(Robinson hall)under the far-sighted direction of Miss K.McNamara to whose kindness in locating the origin-destination studies mentioned in the text I am deeply indebted.

42. The only information I can find on the subject of traffic density on elevators is in Aust, F.A. & H.F.Janda, A Method of Making Short Traffic Counts and Estimating Traffic Circulation in Urban Areas[R]. University of Wisconsin, 1931, where I find the statement(p.50)without data, “Street car traffic acts like traffic in an elevator which is heaviest on the ground floor, while decreasing proportionally the higher up it goes.”

43. My students, at that time Messrs. R.C.Bernard, Jr., W.B.Bryant, A.Y.Davis, and S.L.Washburn, measured the traffic distributions on the above survey maps. Mr. Bernard prepared the chart of Fig.9-12 from the Milwaukee and Metropolitan Area Origin-Destination Traffic Survey, 1946, Figs.17, 18, and 19.

44. Extremely important in this connection is the observation by Stewart, J.Q. “Suggested principles of ‘social Physics’,” op.cit., p.180, that the rural nonfarm rent in 28 states east of Colorado and north of the Deep South was on the average proportional to the “potential of population” as defined by Dr.Stewart(closely related to the(P1P2)/D relationship). In this article Dr.Stewart reports measurement of densities from city limits to city centers.

45. Bossard, J.H.S. “Residential propinquity as a factor in marriage selection,” American Journal of sociology[J]. Vol.38, 1932:219—224.

46. Davie, M.R. & R.J.Reeves, “propinquity of residence before marriage,” American Journal of Sociology[J]. Vol.44, 1939:510—517.

47. Abrams, R.H. “residential propinquity as a factor in marriage selection: fifty year trends in Philadelphia,” American sociological Review[J]. Vol.8, 1943:288—294.

48. The literature on this subject is very large. Reference is made to the specialized journals. Particularly penetrating into the semantics of the problem is the excellent article by Lundberg G.A. & V.Beazley, “Consciousness of kind in a college population,” Sociometry[J]. Vol.11, 1948:Nos.1—2; pp.59—74.

49. Stouffer, F.A. “intervening opportunities: a theory relating mobility and distance,” American sociological Review[J]. Vol.5, 1940:845—867. See also Thomas, D.S. “Interstate migration and intervening opportunities,” ibid., Vol.6, 1941:773—783, Isbell, E. “Internal migration in Sweden and intervening opportunities,” ibid., Vol.9, 1944:627—639.

50. This hypothesis about radio stations that was first published in Zipf, G.K. “On Dr.Miller's contribution,” op.cit, has been confirmed empirically by my student, Mr.J.P.Boland, whose important paper, “On the number and sizes of radio station in relation to the populations of their cities,” appears in Sociometry[J]. Vol.11, 1948:111—116.

51. Lotka, A.J. “The frequency distribution of scientific productivity,” Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences[J]. Vol.16, 1926:320. The percentage should be less than 60% for our equation which contains the b constant.

52. Ayer N.W. & Son's Directory of Newspapers and Periodicals[M]. Philadelphia: N.W.Ayer and Sons, Inc., 1941:1139—1160.

53. Previously reported, Zipf, G.K. “The hypothesis of the Minimum Equation' ...,” op.cit, p.648 f., and also in his “On the number. circulation sizes, and the probable purchasers of newspapers” American Journal of Psychology[J]. Vol.41, 1948:83—92. For all the extensive measurements and calculations that underlie Table 9-1 I am grateful to the following students of mine: the Misses A.R.Boyle, R.Cunningham, G.Peterson, and Messrs. R.C.Bernard, Jr, J.P.Boland, D.D.Bourland. Jr., C.Bridge, Jr., W.B.Bryant, J.M.Conant, A.Y.Davis, A.Fellow, J.M.Gillespie, R.V.Johnson, M.I.Liebmanm, T.Macklin, D.G.Outerbridge, R.L.Perry, D.D.Scarlett, J.A.Sevin, J.D.Stanley, S.L.Washburn and W.S Wheeling.

54. Ibid. My students, Messrs. J.M.Conant and A.Y.Davis have observed that the N number of different periodicals that issue(editorial office)from a city of P population size varies directly with P. “A measurement of the number and diversity of periodicals in ninety-two American cities,” Sociometry, Vol.11(1948), 117—120; William R.Chandler, Relationship of distance to the occurrence of pedestrian accidents, ibid., 108—110.

55. In this connection, cf. Thompson, D.W. On Growth and Form[M]. New York Macmillan, 1943.

第十章

1. Presented in greater detail in Zipf, G.K. National Unity and Disunity[J]. Bloomington, Ind.: Principia Press, 1941:21—24.

2. For a further discussion of conditions of surfeit and of deficiency with graphical representation cf. ibid., 27—40.

3. Discussed in greater detail ibid., 40—46. The topic has been treated by one of America's outstanding experts in the regionalism of the Souch, cf. Odum, H.W. An American Epoch[M]. New York Holt, 1930; also(with Moore, H.E.), American Regionalism[M]. New York: Holt, 1938. His recent treatise Understanding Society[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1947, merits careful study.

4. The concept of the saturation point of community organization within a nation has been discussed in detail in Zipf, G.K. National Unity and Disunity[M]. op.cit., Chap.2.

5. Stewart, J.Q. “Empirical mathematical rules concerning the distribution and equilibrium of population”, The Geographical Review[J]. Vol., 1947:468—469.

6. The case of Germany has been treated in greater detail in Zipf, G.K. National Unity and Disunity[M]. op.cit., 135f., 140f.

7. The case of Austria is discussed in greater detail ibid., 191—197.

8. Ibid.

9. For an interesting discussion of the Harvard “intelligentsia”, cf. Sargent, Porter. Mad or Muddled?[M]. Boston: 11 Beacon St., 1947. Also his The Continuing Battle for the Control of the Mind of Youth[M]. Boston: 11 Beacon St., 1945; also his Getting Us into War; and his Education in Wartime which are published from the same address. Let us hope that Mr. Sargent probes a little more deeply.

10. E.g., Svend Riemer's review of National Unity and Disunity in the September, 1942, issue of the American Journal of Sociology[J].(pp.285—287). This review, which apparently represents the view of one European school of sociologists, is particularly interesting to read today. For my reply, cf. ibid., Vol.48(January, 1943), 503—504 in which are presented evaluations of scholars of the American tradition.

11. We hope to return to this topic in a future treatment of the societal pathology of an educational institution which will be presented in a more popular style.

12. Presented in greater detail in Zipf, G.K. National Unity and Disunity[M]. op.cit., Chap.4.

13. For the date on French communities, cf. ibid.

14. Discussed in detail ibid, Chap.5.

15. Ibid.

16. The case of the British Empire is discussed in greater detail ibid.

17. The case of Europe is discussed in greater detail ibid.

第十一章

1. Equation 11-2b is discussed in reference to historical consideration in Zipf, G.K. National Unity and Disunity[M]. Bloomington, Ind.: Principia Press, 1941, Chap.5.

2. An excellent account of the empirical aspects of the Pareto school in reference to the distribution of individual incomes can be found in Davis, H.T. The Theory of Econometrics[M]. Bloomington, Ind.: Principia Press, 1941, 17—53 and passim. Later in this chapter we shall discuss the above in greater detail.

3. This statement that is so frequently impute to J.J.Rousseau seems to evade specific reference although its sense is apparent in his Contrat social. I am grateful to my colleague, Professor M.Franon, for his generous help in this matter.

4. These terms are borrowed from the current political language of an academic hierarchy with which the present writer happens to be familiar.

5. This concept of the economic value of prestige symbols was developed by the late Edward Sapir in his brilliant Tercentenary Lectures at the Harvard Summer School in 1936 which I heard. For a complete bibliography of Edward Sapir's publications, cf. Ruth Benedict's obituary of Edward Sapir, American Anthropologist[J]. vol.41, 1939:469—477. Perhaps the best general view of Professor E. Sapir's school of thinking is to be found in L.Spier, A.I.Hallowell, and S.S.Newman, Editors, Language, Culture, and Personality[M]; Essays in Memory of Edward Sapir[M]. Menasha, Wisc.: Sapir Memorial Publication Fund, 1941.

6. One is reminded of the famous concept of D.Bernoulli of the increment of wealth in the utility of money, cf. Daniel Bernoulli “Specimen Theoriae Novae de Mensura Sortis,” Commentari Acad. Petropol.[J]. Vol.5, 1730—1731, published 1738, p.175—192(reference from Davis, H.T. The Theory of Econometrics, op.cit., p.82, original not seen). Dr.Davis, H.T. op.cit., Chap.3, and notably p.74 f., discusses Bernoulli's concept in connection with what is called the Weber-Fechner Law in psychology: “In order that the intensity of a sensation may increase in arithmetical progression, the stimulus must increase in geometrical progression”(before accepting the above formulation of the Weber-Fechner Law as a description of fact in sensation, one may profitably read the able discussion of the Law in Boring, E.G. Sensation and Perception in the History of Experimental Psychology[M]. New York: Appleton-Century, 1942, passim.; one may also profitably inspect some of the actual measurements of eminent physiologists like Dr.W.J.Crozier, for references to whose work, cf., index under Crozier, ibid. and also in Biological Abstracts and Psychological Abstracts[M]. We remember, in general, that the manifestation of a principle in the operation of a machine is subject to the limitations of the machine which may have been designed to discharge additional tasks according to other principles under the general theoretical Principle of the Economical Versatility of Tools). For a statement of Bernoulli's famous postulate relative to the satisfaction that a man receives in adding an increment of wealth to his fortune as well as a statement of alternative postulated equations by C.Jordan and by R.Frisch, cf. Davis, H.T. The Theory of Econometrics[M]. op.cit., Chap.3. Although our(theoretical)Exponential Law of Incentives is not based upon any of the foregoing postulates, but upon our own argument, nevertheless the phenomenon under consideration is the same; and if our argument be sound it may support one of the postulates, etc., with the result that a synthesis of several viewpoints may be possible with a common mathematical description.

7. The argument expressed in this footnote would seem to provide a rationalization of not a few of the numerous observations(reference must be made to the specialized literature)in which, superficially stated, socio-economic likes show a preference for an interaction with socio-economic likes, even in reference to the minutiae of social conduct. As examples of the studies in question which, for the most part, contain important bibliographies, cf. Burgess E.W. & P.Wallin, “Homogamy in social characteristics,” American Journal of Sociology[J]. Vol.49, 1943:109—124; Nelson, L. “Intermarriage among nationality groups in a rural area of Minnesota,” ibid., 585—592; Tietze, C. & P.Lemkau & M.Cooper, “Personality disorder and spatial mobility,” ibid., Vol.48(1942), 29—39; Schroeder, C.W. “Mental disorders in cities,” ibid., 40—47; Binder-Johnson, H. “Distribution of the German pioneer population in Minnesota,” Rural Sociology[J]. Vol.6(1941), ginia Beazley, “Consciousness of kind in a college population,” Sociometry[J]. Vol.11, 1948:59—74.

8. Ernst Engel, the nineteenth century German economist, whose studies of family budgets led to the following formulation(“Engel's Law” and “Engel Curves”): with increasing family income the percentage spent on necessities like food decreased, whereas the percentage spent on luxuries increased, while that spent on intermediate classes like clothing and shelter remained constant. Cf. Elmer, M.C. The Sociology of the Family[M]. Boston: Ginn, 1945; Davis, H. The Theory of Econometrics[M]. op.cit., Chap.8 with extensive bibliography. Cf. also Conant, J.M. Statistical Treatment of Spending Behavior[D]. Honors Thesis for the Bachelor's Degree at Harvard University June Commencement, 1948, in which there are extensive measurements of budgets and classes of expenditures including governmental expenditures. Mr. Conant has reported to me privately his observation that the estimated length of time covered by different courses in history(and in English literary history)at Harvard University, when ranked in the old of decreasing length, reveals an approximation of the proportions of the harmonic series which, incidentally, would seem to tie in with our theoretical argument in Chaps. 4 and 5 in reference to the economies of Generic and of Specific correlations, and the economies of Versatility and of Specialization.

9. Let us not forget that according to “Engel's Law”(cf. preceding footnote), the percentage amount spent for shelter observably tends to be a constant of the family income. Hence, Ernst Engel and his followers have observed empirically what we derived theoretically from our above second analogue(supra).

10. Historically considered, “Engel's Law,” despite the fact that its linearity fails to hold for large incomes and for expenditures on luxuries, was, I believe, instrumental in introducing the graduated income taxes of today.

11. For a nontechnical discussion cf. Sax, K. “Population problems of a new world older,”Scientific Monthly[J]. Vol.58, 1944:66—71. See also Pearl, R. Natural History of Population[M]. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1939.

12. For the case of distance of motor vehicle accidents to pedestrians in relation to their D distance from home, cf. Chandler, W.R. “The relationship of D distance to the occurrence of pedestrian accidents.” Sociometry[J]. Vol.11, 1948:108—110.

13. Snyder, C. Capitalism the Creator[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1940.

14. This consideration is elaborated in very considerable detail in Zipf, G.K. National Unity and Disunity[M]. Bloomington, Ind.: 1941, Chap.5.

15. Pareto, V. The Mind and Society: a Treatise on General Sociology[M].(English translation), New York: Harcourt Brace, 1935. For an excellent treatment of Pareto. cf. Homans G.C. & C.P.Curtis, An Introduction to Pareto[M]. New York: Knopf, 1934. Also analyzed critically in Parsons, T. The Structure of Social Action[M]. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1937.

16. The writings of most of above social scientists can be found cited for the most part in any standard treatise on sociology(for their books, cf. Library of Congress cards). Their articles, expect for Wesley C.Mitchell, the economist, and A.Korzybski, have been published mostly in the standard journals of sociology(e.g., The American Sociology Review, Social Forces, The American Journal of Sociology). Cf. Mitchell, W.C. “The public relations of science,” Science[J]. Vol.90, 1939:599—607. Cf. Korzybski, A. Science and Sanity[M]. op.cit. The mathematical studies of Professor N.Rashevsky, though by no means devoted exclusively to human social relations, nevertheless make a significant contribution to the growing literature of social theory. In particular see his “Outline of a mathematical theory of human relations,” Philosophy of Science[J]. Vol.2, 1935:413—429; “Further studies on the mathematical theory of human relations,” Psychome-trika[J]. Vol.1, 1936:21—36; “Studies in mathematical theory of human relations,” ibid., Vol.4, 1939:221—239; continued ibid., 283—299. See also his recent book, Mathematical Theory of Human Relations[M]. Bloomington, Ind.: Principia Press, 1947. For the most recent statement of the Dodd theory of Dimensional Analysis, cf. Dodd, S.C. “A systematics for sociometry and for science,” Sociometry[J]. Vol.11, 1948:11—30. See also Cervinka, V. “A dimensional theory of groups,” ibid., pp.100—107.

17. Wilson, E.B. “What is social science?” Science[J]. Vol.92, 1940:157—162. I refer to his statement beginning, “Indeed, unless I am much mistaken, so great is the prestige of this sort of thinking and writing on the part of those who are in a position to award recognition for work in social lines ...” See also his “Methodology in the natural and the social science,” American Journal of Sociology[J]. Vol.45, 1940:655—668.

18. Lundberg, G.A. Can Science Save Us[M]. New York: Longmans, Green, 1947; Foundations of Sociology[M]. New York: Macmillan, 1939. See also presidential address at the 38th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Society, New York. Dec., 1943, “Sociologists and the peace,” published in the American Sociological Review[J]. Vol.9, 1944:1—13.

19. Chapin, F.S. “Social obstacles to the acceptance of existing social science knowledge,” Social Forces[J]. Vol.26, 1947:7—12.

20. In addition to A.Korzybski's own writings, see also the publications of the Institute of General Semantics, Chicago, Ill., including the papers of the Second American Congress on General Semantics(held at Denver University, 1941); also the General Semantics Monograph, Iowa City: Institute of General Semantics, 1939 and following. For complete bibliography on general semantics and for the program for the coming Congress of General Semantics in Denver, 1949, contact Miss M.Kendig, Institute of General Semantics, Lakeville, Conn.

21. Johnson, W. People in Quandaries[M]. New York: Harpers, 1946.

22. The income tax date presented herewith have been presented previously and discussed in detail along with further income tax date in Zipf, G.K. Natural Unity and Disunity[M]. op.cit., Chap.5. For a virtually complete bibliography of income date and of significant studies of the same through 1940 cf. Davis, H.T. The Theory of Econometrics[M]. op.cit., 51—53 and passim.

23. Ibid.

24. For the discussion of a theory of revolution, cf. Davis, H.T. The Theory of Econometrics[M]. op.cit., 200—205 and also chap.2. passim. For a discussion of the revolutionary implication of bends and changes of slope in income curves, cf. Zipf, G.K. Natural Unity and Disunity[M]. op.cit., Chap.5.

25. For the summary of Pareto's own observations which refer to date from 1471 to 1894, cf. Davis, H.T. The Theory of Econometrics[M]. op.cit., p.30; with many further sets of observations ibid., Chap.2.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid., p.51.

28. Lotka, A.J. “The frequency distribution of scientific productivity,”Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences[J]. Vol.16, 1926:317—323.

29. Davis, H.T. The Theory of Econometrics[M]. op.cit., p.49.

30. Since this text was written a further set of date has been made available in the 146th Annual Report of E.I.du Pont de Nemours and Company for the year 1947, which is particularly interesting because the range of annual salary or wage is given both gross before federal taxes and net after federal taxes. These date farsightedly raise the knotty question of whether we should view a wage or salary as the gross amount paid by the employer, or as the net amount received by the employee. With the very heavy taxation of individual incomes, employers may have to bargain ever more in terms of “take-home pay.” In this connection one might profitably read the theory of revolution of H. T. Davis, loc cit., p.200 f.

31. Myslivec, V. “Paretos Funktion und ihre Anwendung zur rationellen Berechnung der Versicherungstarife in der Automobilversicherung,” Archiv für mathematische Wirtschafts-und Sozialforschung[J]. Vol.5, 1939:51—68; data pp.57 and 59.

32. Before leaving the topic of individual incomes we call attention to the observation of Reilly, W.J. Methods for the Study of Retail Relationships[C]. University of Texas Bulletin, No.2944(Nov.22. 1929), Fig.1, p.20, which shows(8 points plotted)how large the x size of a typical city must become before it controls the style goods trade of the various y income classes. According to my eye, for income classes above $4 500 the function is

This function as disclosed by W.J.Reilly, who also first formulated the “law of retail gravitation” and first observed precisely the P/D function in the circulation of a newspaper, ibid(cf. our Chap, 9 supra). The above function suggests that the higher priced styles are in large cities. If we now assume that persons live their sources of supplies, then the richer persons will tend to live in the large cities, as is to be inferred theoretically from our “grand analogue” in Section I of this chapter. Reilly's observation seems to be susceptible of theoretical synthesis with the deduction[Zipf, G.K. “On the frequency and diversity of business establishments and personal occupations,” etc., Journal of Psychology[J]. Vol.24, 1947:139—148]that the rank frequency distribution of occupations and of establishments within cities will follow the equation of the harmonic series(p=1)with the value of the constant, F·Sn, varying directly with the city's P size—a deduction that has subsequently been confirmed by my student, Mr.D.David Bourland, Jr., in the case of “professions” as disclosed from the date of Classified Telephone Directories(to be published in his article entitled, “On the distribution of professions within cities in the United States”).

May we perhaps not argue that the distribution of incomes within cities is distributed according to our equations, and that the constant in the income equations varies directly with the city's P size? Surely Reilly's observations in his Fig.1(loc. cit.)are consistent with such a theoretical expectation.(According to our argument, the N number of cities of P size varies inversely with the square of P size, while the N number of incomes of like size varies inversely with the cube of income size.)

The problem seems to merit further empiric study and theoretical elaboration.

33. Discussed more fully in Zipf, G.K. National Unity and Disunity[M]. op.cit., Chap.5. The relationship between group incomes and individual incomes seems to be an example of the “square effect.”

34. Presented and discussed more fully ibid.

35. Chapple, E.D. “‘Presonality’ differences as described by invariant properties of individuals in interaction,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences[J]. Vol.26, 1940:10—16. See also Norwine A.C. & O.J.Murphy, “Characteristic time intervals in telephonic conversation,” The Bell System Technical Journal[J]. Vol.17, 1938:281—291(also published separately in Bell Telephone System Technical Publications, Monograph B-074).

36. Cf. for example, Chapple, E.D. “The analysis of industrial morale,” The Journal of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology[J]. Vol.24, 1942:163—172. This contains reference to further important publications by Dr.Chapple. In collaboration with the distinguished ethnologist, C.S.Coon, Dr.Chapple enunciated his principles of anthropology, cf. Chapple, C.D. & C.S.Coon, Principles of Anthropology, New York: Holt, 1942.

37. Lotka, A.J. “The frequency distribution of scientific productivity,” Journal of the Washington Academy of sciences[J]. Vol.16, 1926:317—323. For the productivity of 278 authors of mathematical papers as ascertained by Dr.Arnold Dresden, cf. Dresden, A. “A report on the scientific wok Chicago Section, 1897—1922,” Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society[C]. Vol.28, 1922:303—307, discussed by Davis, H.T. The theory of Econometrics[M]. op.cit., p.48.

38. This vying for attention by those who have goods and services for sale has been studied quite interestingly by my three students, Messrs. W.Baird Bryant, Stephen L.Washburn, and Donald G.Outerbridge in connection with the advertisements of a classified telephone directory(to be published shortly by them in an article entitled “some psychological determinants of the structure of advertising in a classified telephone directory,” American Journal of Psychology[J]. in press.)

第十二章

1. Veblen, T. The Theory of the Leisure Class[M]. new Ed. New York: Macmillan, 1919. The edition of the Modern Library has a valuable preface by Mr. Stuart Chase.

2. Chapple E.D. & C.S.Coon, Principles of Anthropology[M]. op.cit., Chap.20.

3. Van Gennep, A.L. Les Rites de Passage[M]. Paris, 1909, cited in E.D.Chapple and C.S.Coon, Principles of Anthropology[M]. New York; Holt, 1942(original not seen).

4. de Saussure, F. Cours de Linguistique Generale[M]. 2nd Ed., Paris: Payot et Cie., 1922.

5. The same argument applies to W.J.Reilly's “law of retail gravitation,” as well as to the subsequent related formulations by P.D.Converse, and J.Q.Stewart(loc. cit., chap.9 supra). It is also basic to the pioneer traffic study of A.M.Wellington(loc. cit., chap.9 supra).

6. Chapin, F.S. “A theory of synchronous culture cycle,” Social Forces[J]. Vol.3, 1925:596—604, Cf. William F.Ogburn's important hypotheses in Ogburn, W.F. Social Change[M]. 5th Ed, New York: Viking, 1928:103—111.

7. Hart, H. “Logistic social trends,” American Journal of Sociology[J]. Vol.50, 1945:337—352.

8. Ibid.

9. Hart, H. “Depression, war, and logistic trends,” American Journal of Sociology[J]. Vol.52, 1946. See also Hertz, H. “Expectations of life as an index of progress,” American Sociological Review[J]. Vol.9, 1944:609—621.

10. President's Research Committee, Recent Social Trends[R]. New York: McGraw-Hill(Vol.1)1933:306.

11. Hagood, M.J. Statistics for Sociologists[J]. New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1941:288, Fig.31.

12. Hart, H. “Logistic social trends,”[R]. op.cit., p.342.

13. Reported in Zipf, G.K. “on the dynamic structure of concert programs.” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology[J]. Vol.41, 1946:25—36.