3.1Earthquake

Definition of earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves.

Earthquakes can range in size from those that are so weak that they cannot be felt to those violent enough to propel objects and people into the air, and wreak destruction across entire cities.

The seismicity, or seismic activity, of an area is the frequency, type, and size of earthquakes experienced over a period of time. The word tremor is also used for non-earthquake seismic rumbling.

Earthquakes

Video from NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

Types of earthquake

Earthquakes include the following types such as aftershock, blind thrust earthquake, glacial cryoseism, deep-focus earthquake, earthquake swarm, foreshock, harmonic tremor, induced seismicity, interplate earthquake, intraplate earthquake, megathrust earthquake, remotely triggered earthquakes, slow earthquake, submarine earthquake, supershear earthquake, strike-slip earthquake, tsunami earthquake and volcano tectonic earthquake.

The above classification criteria are different, some according to the focal depth, some according to the earthquake inducement factor.

Characteristics

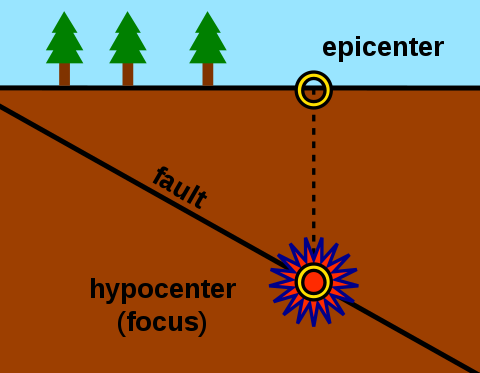

A hypocenter (or hypocentre) (from Ancient Greek: ὑπόκεντρον [hypόkentron] for 'below the center') is the point of origin of an earthquake or a subsurface nuclear explosion. In seismology, it is a synonym of the focus. The term hypocenter is also used as a synonym for ground zero, the surface point directly beneath a nuclear airburst. An earthquake's hypocenter is the position where the strain energy stored in the rock is first released, marking the point where the fault begins to rupture.

The epicenter, epicentre or epicentrum in seismology is the point on the Earth's surface directly above a hypocenter or focus, the point where an earthquake or an underground explosion originates.In most earthquakes, the epicenter is the point where the greatest damage takes place, but the length of the subsurface fault rupture may indeed be a long one, and damage can be spread on the surface across the entire rupture zone.

This occurs directly beneath the epicenter, at a distance known as the focal or hypocentral depth.The focal depth can be calculated from measurements based on seismic wave phenomena. As with all wave phenomena in physics, there is uncertainty in such measurements that grows with the wavelength so the focal depth of the source of these long-wavelength (low frequency) waves is difficult to determine exactly. Very strong earthquakes radiate a large fraction of their released energy in seismic waves with very long wavelengths and therefore a stronger earthquake involves the release of energy from a larger mass of rock.

Intensity of earth quaking and magnitude of earthquakes

Prior to the development of strong-motion accelerometers that can measure peak ground speed and acceleration directly, the intensity of the earth-shaking was estimated on the basis of the observed effects, as categorized on various seismic intensity scales. Only in the last century has the source of such shaking been identified as ruptures in the Earth's crust, with the intensity of shaking at any locality dependent not only on the local ground conditions but also on the strength or magnitude of the rupture, and on its distance.

Seismic intensity scales categorize the intensity or severity of ground shaking (quaking) at a given location, such as resulting from an earthquake. They are distinguished from seismic magnitude scales, which measure the magnitude or overall strength of an earthquake, which may, or perhaps not, cause perceptible shaking.

Intensity scales are based on the observed effects of the shaking, such as the degree to which people or animals were alarmed, and the extent and severity of damage to different kinds of structures or natural features. The maximal intensity observed, and the extent of the area where shaking was felt (see isoseismal map, below), can be used to estimate the location and magnitude of the source earthquake; this is especially useful for historical earthquakes where there is no instrumental record.

Seismic magnitude scales are used to describe the overall strength or "size" of an earthquake. These are distinguished from seismic intensity scales that categorize the intensity or severity of ground shaking (quaking) caused by an earthquake at a given location. Magnitudes are usually determined from measurements of an earthquake's seismic waves as recorded on a seismogram. Magnitude scales vary on what aspect of the seismic waves are measured and how they are measured. Different magnitude scales are necessary because of differences in earthquakes, the information available, and the purposes for which the magnitudes are used.

"Richter" magnitude scale

The first scale for measuring earthquake magnitudes, developed in 1935 by Charles F. Richter and popularly known as the "Richter" scale, is actually the Local magnitude scale, label ML or ML. Richter established two features now common to all magnitude scales.

First, the scale is logarithmic, so that each unit represents a ten-fold increase in the amplitude of the seismic waves. As the energy of a wave is 101.5 times its amplitude, each unit of magnitude represents a nearly 32-fold increase in the seismic energy (strength) of an earthquake.

Second, Richter arbitrarily defined the zero point of the scale to be where an earthquake at a distance of 100 km makes a maximum horizontal displacement of 0.001 millimeters (1 µm, or 0.00004 in.) on a seismogram recorded with a Wood-Anderson torsion seismograph. Subsequent magnitude scales are calibrated to be approximately in accord with the original "Richter" (local) scale around magnitude 6.

All "Local" (ML) magnitudes are based on the maximum amplitude of the ground shaking, without distinguishing the different seismic waves.

The original "Richter" scale, developed in the geological context of Southern California and Nevada, was later found to be inaccurate for earthquakes in the central and eastern parts of the continent (everywhere east of the Rocky Mountains) because of differences in the continental crust. All these problems prompted the development of other scales.

Measuring and locating earthquakes

The instrumental scales used to describe the size of an earthquake began with the Richter magnitude scale in the 1930s. It is a relatively simple measurement of an event's amplitude, and its use has become minimal in the 21st century. Seismic waves travel through the Earth's interior and can be recorded by seismometers at great distances. The surface wave magnitude was developed in the 1950s as a means to measure remote earthquakes and to improve the accuracy for larger events. The moment magnitude scale not only measures the amplitude of the shock but also takes into account the seismic moment (total rupture area, average slip of the fault, and rigidity of the rock). The Japan Meteorological Agency seismic intensity scale, the Medvedev–Sponheuer–Karnik scale, and the Mercalli intensity scale are based on the observed effects and are related to the intensity of shaking.

Earthquakes are not only categorized by their magnitude but also by the place where they occur. Standard reporting of earthquakes includes its magnitude, date and time of occurrence, geographic coordinates of its epicenter, depth of the epicenter, geographical region, distances to population centers, location uncertainty, a number of parameters that are included in USGS earthquake reports (number of stations reporting, number of observations, etc.), and a unique event ID.

Although relatively slow seismic waves have traditionally been used to detect earthquakes, scientists realized in 2016 that gravitational measurements could provide instantaneous detection of earthquakes, and confirmed this by analyzing gravitational records associated with the 2011 Tohoku-Oki ("Fukushima") earthquake.

Quiz

Topic Discussion

References

Ohnaka, M. (2013). The Physics of Rock Failure and Earthquakes. Cambridge University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-107-35533-0.

Vassiliou, Marius; Kanamori, Hiroo (1982). "The Energy Release in Earthquakes". Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 72: 371–387.

Spence, William; S.A. Sipkin; G.L. Choy (1989). "Measuring the Size of an Earthquake". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2009-09-01. Retrieved 2006-11-03.

Stern, Robert J. (2002), "Subduction zones", Reviews of Geophysics, 40 (4): 17, Bibcode:2002RvGeo..40.1012S, doi:10.1029/2001RG000108

Geoscience Australia

Wyss, M. (1979). "Estimating expectable maximum magnitude of earthquakes from fault dimensions". Geology. 7 (7): 336–340. Bibcode:1979Geo.....7..336W. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1979)7<336:EMEMOE>2.0.CO;2.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earthquake