Reading A Discussion

The role of concentrated solar power with thermal energy storage in least-cost highly reliable electricity systems fully powered by variable renewable energy

4. Discussion

4.1. CSPwith TES as a storage technology

Both dispatch behavior and cost sensitivity analysis suggest that the primary gridservice value of CSP arises from coupling with cheap TES, rather than as adirect generation technology. CSP+TES provides valuable grid services mostlyrelative to batteries rather than relative to PV generation, with cost benchmarks tied to battery costs for when CSP+TES is a contributor toleast-cost systems that meet 100% of demand. In the base case for these 100% reliable idealized least-cost electricity systems, the CSP + TES grid services niche would be eliminated if the ratio of battery costs to other technology costs decreased by 40%. NREL projects that battery costs will reach40% of their current level by 2050, or even as soon as 2030 in the most aggressive projection [17].

Aggressive cost reductions would be required to allow parabolic trough CSP to be deployed in the modeled least-cost systems at those battery costs, but given the relative maturity of CSP technology, these reductions are considered unlikely [21,66,67].The less mature solar power tower technology could potentially achieve more substantial cost reductions, with DOE SunShot goals calling for a 50% reduction of 2010 costs by 2030 [68]. Although CSP generation costs include both the solar field and the steam turbine, the maturity ofthe steam turbine technology due to extensive usage in other contexts makes the solar field the most likely target for innovation [69]. Turbine efficiency could be improved if higher temperatures could be obtained from the solar field, which would then lower the overall cost of CSP energy generation [70].

Even substantial cost reductions for solar power towers would only maintain CSP+TES's role as a short-duration storage technology in these idealized least-cost VRE-dominated 100% reliable electricity systems. In our modeled systems, the 50% cost reduction called for in the SunShot goals was not sufficient to convert CSP into a bulk power provider. For example, Fig. S14 shows that CSP generation became a substantial contribution to the asset mix at 25% of base case costs. Reductions in the cost of CSP and TES also would note liminate the need for long-duration storage such as PGP. The need for seasonal storage decreased in idealized least-cost reliable systems when CSP generation costs were very cheap, but PGP was not eliminated from the asset mix until either CSP or TES were nearly free. Overall, penetration of CSP+TES in these highly reliable variable renewable electricity systems is very limited, with CSP+TES costs struggling to compete with declining battery costs.

4.1.1. CSPwith TES in a system without long-duration storage

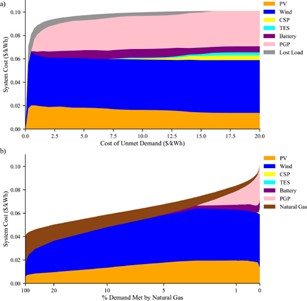

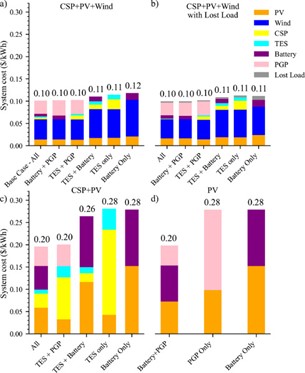

Without PGP, the analysis shows that batteries and TES were used relatively infrequently, only using the full built capacity during the periods of seasonal resource lows (Figs. S5-S11). In this regime, the addition of CSP+TES to a battery-only idealized 100% VRE/storage system decreased system costs by ∼7% (Fig. 5). Notably, TES is the preferred technology in this analysis to add the final measure of flexibility needed to reach a reliable100% VRE-based system. This behavior was seen both when gradually eliminating natural gas from the system (Figs. 4(b) and S11), and when allowing the system to include unmet demand (Figs. 4 and 5).When CSP+TES was removed to leave a battery-only VRE/storage system (Fig. 5),least-cost systems resulted in additional lost load as opposed to meeting the extra demand with batteries. The cheaper storage from TES made TES a more valuable technology for the highly infrequent use needed in idealized VRE-dominated least-cost systems that did not contain long-duration storage.The modeling indicates that the strongest incentives to build CSP+TES occur insystems without firm generators, long-duration storage, or other mechanisms to obtain grid flexibility.

Fig. 4. Alternative grid flexibility mechanisms.System response to the cost placed on unmet demand in (a). System response when the dispatch from natural gas was limited in (b). All systems were modeled using 2017 data for resource availability and demand. These results indicate that CSP with TES, at current ratios of costs, provides valuable grid serviceswhen other approaches to grid flexibility are severely limited. PV refers tosolar photovoltaics; CSP is concentrating solar power; TES is thermal energystorage; PGP is power-to-gas-to-power.

Fig. 5. Technology combinations, with and without unmet demand. CSP+TES and PV coexist. Wind minimizes need for CSP+TES overnight storage, and unmet demand pushes CSP+TES out of idealized least-cost 100% reliable 100% VRE-based electricity systems. Additional combinations are shownin Fig. S13.

4.2. Considerations for CSP and TES integration into renewable systems

Across a range of scenarios and costs, CSP with TES maintained a small role inidealized least-cost systems that met 100% of demand. This finding was also verified across multiple years of input data between 2016 and 2019 to ensure that the 2017 base case year was not an outlier year despite the expected inter-annual variability of wind, solar, and demand data (Fig. S2) [71]. Unless CSP costs were assumed to reach less than 50% ofcurrent levels, CSP+TES primarily acted as a “last 1%” peaker technology. This behavior suggests that efforts to increase demand-side flexibility could minimize the value of CSP to satisfying resource adequacy planning constraintsin such electricity systems. NREL's Electrification Futures Study suggests the potential for large shifts in peak demand behavior, particularly in the case of widespread usage of electric vehicles [72]. Although this analysis shows that CSP+TES has a limited role adding flexibility to a VRE grid with currently available technologies and costs, that role could be filled by other flexibility mechanisms in future electricity systems. In regions other than the US, short-duration storage should remain the main role for CSP+TES,but the size of that niche role would depend on the particular resource and demand characteristics for that region. Therefore, although the overall conclusions described here may be generally applicable, a quantitative assessment will require analysis based on the specific characteristics of each individual region.

4.2.1. Impact of firm generators

Firm generators with low- or zero-carbon emissions could also minimize the need forstorage technologies, reducing the need for CSP+TES to contribute grid flexibility. The impact of adding such firm generators was evaluated by allowing for either natural gas with CCS (Fig. S12) or nuclear power (Fig. S16)to be included in the modeled least-cost electricity systems. For systems with natural gas with CCS, CSP+TES was present in the idealized least-cost systemonly if natural gas with CCS was limited to ≤ 3% of total dispatch. The inclusion of nuclear power reduced the role of CSP+TES, but CSP+TES was nevertheless used in combination with batteries to smooth out sharp demand peaks, supplying ∼0.1% of demand. Clearly, these firm generator technologies couldplay a role in meeting demand for electricity systems with large amount of generation from variable renewable resources, but such technologies are often limited from future electricity systems by regulation or mandate [1].Dispatchable hydropower was not considered here, but would be expected to have a similar impact in our idealized least-cost system to the other dispatchable technologies that were modeled, such as natural gas. Geographical and other limitations on hydropower generation also prevent it from fully eliminating the need for variable renewables, with limited hydropower growth expected in the US through 2050 [73]. Regardless of firm generators,some amount of variable renewables are expected in future electricity systems,which will likely require either curtailment or storage of some of that variable generation. Our analysis indicates that under certain albeit limited conditions, CSP+TES is a viable option to provide such storage, and remains so even at relatively low penetration of variable renewables, as seenin Figs. 4(b), S12, and S16.

4.3. Limitations

This model assumes free, lossless transmission across the contiguous US, without separation into more geographically constrained load-balancing regions. The hourly time resolution in the model assumes that load balancing and grid stabilization on shorter time scales will be provided by other currently available technologies. If transmission were limited, greater variability inthe solar and wind generation profiles would be expected, as found in previously published work [6]. The increased resource variability would increase the need for energy storage and/or curtailment of excesswind/solar generation, but is not expected to fundamentally alter the assessment of the relative roles and values of the generation and storage technologies evaluated herein. Constraining the geographic region could lead to different mixes of technologies, such as the increased PV and decreased wind deployment due to localized resource availability when only California was considered in previous work [6].

Each model run generates a single end state, so no learning rates were used in cost calculations. The modeled system was assumed to be built instantaneously using“overnight” costs, and the configurations of the modeled least-cost systems were determined using perfect foresight of future resource availability and demand. Consequently, the results herein represent a lower bound for the generation and storage capacity needed to meet electricity demand. The exclusion of offshore wind power from the model is an exception to this lower bound, as wind off the East coast of the US generally has higher capacity factors and less variability [74]. However, offshore generation profiles still exhibit considerable variability,[74,75] and the conclusions of this analysis should not be substantially impacted by this exclusion. No life-cycle considerations for technologies were incorporated into the model.

This analysis does not consider the use of CSP for non-electrical cogeneration products such as heat, desalinated water, or hydrogen [67,76].These uses might improve the economics of CSP implementation beyond what is evaluated here [77]. Hybridization of CSP with biofuels, geothermal, or fossil fuels which could provide benefits such as increased capacity factor, increased efficiency, and cost-reductions from sharing equipment between technologies is also outside the scope of this analysis [30,77]. This analysis also did not considerany capacity credits, tax incentives, mandates, security of supply or geopolitical considerations. Thus, the results presented here represent a conservative estimate of the utility of CSP. Given the possibility for CSP to supply other products such as heat or hydrogen, future work could examine the potential of CSP to contribute to these other sectors rather than solely to electricity. (1556 words)

Notes:

1. Authors:Kathleen M. Kennedy, Tyler H. Ruggles, Katherine Rinaldi, Jacqueline A.Dowling, Lei Duan, Ken Caldeira, Nathan S. Lewis (2022). The role ofconcentrated solar power with thermal energy storage in least-cost highlyreliable electricity systems fully powered by variable renewable energy. Advancesin Applied Energy.

2. Keywords: Macro-energymodeling; Concentrated solar power; Thermal energy storage; Renewables; Energysystems

3. Abstract: Policies in the US increasingly stipulate the use of variable renewable energysources, which must be able to meet electricity demand reliably and affordably despite variability. The value of grid services provided by additional marginal capacity and storage in existing grids is likely very different than their value in a 100% variable renewable electricity system under such policies. Consequently, the role of concentrated solar power (CSP) and thermal energystorage (TES) relative to photovoltaics (PV) and batteries has not been clearlyevaluated or established for such highly reliable, 100% renewable systems. Electricity generation by CSP is currently more costly than by PV, but TES is much less costly than chemical battery storage. Herein, we analyze the role ofCSP and TES compared to PV and batteries in an idealized least-costsolar/wind/storage electricity system using a macro-scale energy model withreal-world historical demand and hourly weather data across the contiguousUnited States. We find that CSP does not compete directly with PV. Instead, TES competes with short-duration storage from batteries, with the coupled CSP+TES system providing reliability in the absence of other grid flexibility mechanisms. Without TES, little CSP generation is built in this system because CSP and PV have similar generation profiles, but PV is currently cheaper on adollar-per-kWh basis than CSP. However, CSP with TES can provide grid flexibility in the modeled least-cost system under some circumstances due to the low cost of TES compared to batteries. Cost-sensitivity analysis shows that penetration of CSP with TES is primarily limited by high CSP generation costs. These results provide a framework for researchers and decision-makers to assessthe role of CSP with TES in future electricity systems.

4. References:

[17] Cole W,Frazier AW. Cost projections for utility-scale battery storage: 2020 up- date.National Renewable Energy Laboratory; 2020. Accessed June 28, 2021https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy20osti/75385.pdf.

[21] Achkari O, ElFadar A. Latest developments on TES and CSP technologies –en- ergy andenvironmental issues, applications and research trends. Appl Therm Eng2020;167:114806. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114806.

[66] Dowling AW,Zheng T, Zavala VM. Economic assessment of concentrated so- lar powertechnologies: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2017;72:1019–32. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.006 .

[67] Sonawane PD,Bupesh Raja VK. An overview of concentrated solar en- ergy and itsapplications. Int J Ambient Energy 2018;39(8):898–903. doi:10.1080/01430750.2017.1345009 .

[68] Murphy C, SunY, Cole W, Maclaurin G, Turchi C, Mehos M. The potential role of concentratingsolar power within the context of DOE’s 2030 solar cost targets. NationalRenewable Energy Laboratory; 2019. Accessed June 28, 2021.https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy19osti/71912.pdf .

[69] U.S.Department of Energy Combined heat and power technology fact sheet series:steam turbines. US Department of Energy; 2016. Published online July, 2016.Accessed June 28, 2021. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2016/09/f33/CHP-Steam%20Turbine.pdf .

[70] Silva-PérezMA. Solar power towers using supercritical CO 2 and supercriti- cal steamcycles, and decoupled combined cycles. In: Advances in concen- trating solarthermal research and technology. Elsevier; 2017. p. 383–402. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-100516-3.00017-4 .

[71] Ruggles TH,Caldeira K. Wind and solar generation may reduce the inter-annual variabilityof peak residual load in certain electricity systems. Appl Energy2022;305:117773. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117773 .

[72] Mai T, JadunP, Logan J, et al. Electrification futures study: scenarios of electrictechnology adoption and power consumption for the united states. NationalRenewable Energy Laboratory; 2018. Accessed June 28, 2021.https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy18osti/71500.pdf .

[1] Shields L.State renewable portfolio standards and goals. In: Proceedings of the nationalconference of state legislatures; 2021. Published January 4. Accessed February5, 2021. https://www.ncsl.org/research/energy/renewable-portfolio-standards.aspx .

[73] HydropowerVision. U.S. department of energy; 2016. Accessed June 28, 2021.https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2018/02/f49/Hydropower-Vision-021518.pdf .

[6] Rinaldi KZ,Dowling JA, Ruggles TH, Caldeira K, Lewis NS. Wind and solar re- sourcedroughts in California highlight the benefits of long-term storage and in-tegration with the Western interconnect. Environ Sci Technol2021;55(9):6214–26. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c07848 .

[74] Budischak C,Sewell D, Thomson H, Mach L, Veron DE, Kempton W. Cost- minimized combinationsof wind power, solar power and electrochemical storage, powering the grid up to99.9% of the time. J Power Sources 2013;225:60–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.09.054.

[75] Mills AD,Millstein D, Jeong S, Lavin L, Wiser R, Bolinger M. Estimating the value ofoffshore wind along the United States’ Eastern Coast. Environ Res Lett2018;13(9):094013. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aada62 .

[76] Gençer E,Mallapragada DS, Maréchal F, Tawarmalani M, Agrawal R. Round-the- clock powersupply and a sustainable economy via synergistic integration of solar thermalpower and hydrogen processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015;112(52):15821–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513488112 .

[77] del Río P,Peñasco C, Mir-Artigues P. An overview of drivers and barriers to concen-trated solar power in the European Union. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2018;81:101929. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.06.038 .

[30] Powell KM,Rashid K, Ellingwood K, Tuttle J, Iverson BD. Hybrid concentrated so- larthermal power systems: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2017;80:215–37. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.067 .