-

1 Reading B

-

2 Task6

-

3 Task7

-

4 Task8

Reading B Results

Climate change impacts and costs to U.S. electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure

3. Results

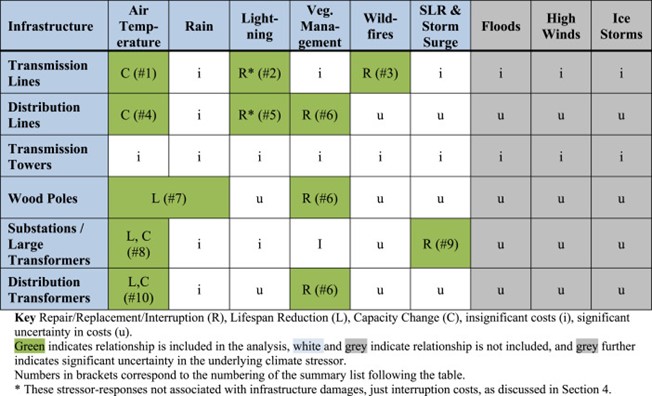

3.1. Results by infrastructure-impact category

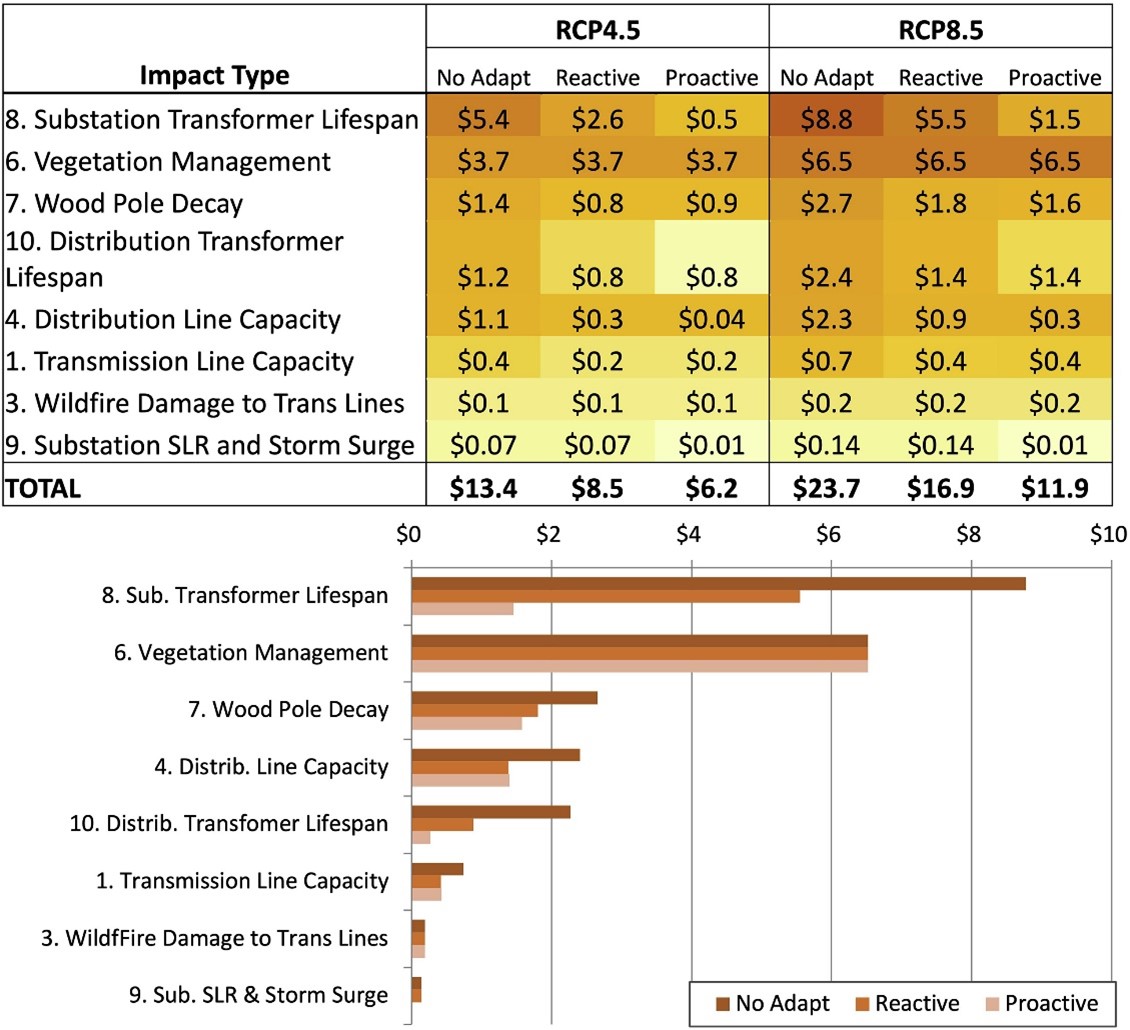

This section presents insights into how the modelled climate change impacts differ across adaptation strategies and emissions scenarios, and vary across the stressor-response categories included in this analysis (previously identified in Table 1). Broadly, we find that climate change reduces grid infrastructure performance and/or reliability. As shown on Fig. 3, total annual economic climate change impacts (with costs ofadaptation) for all stressor response categories at the end of the century range from $6 to $24 billion, depending on emission scenario and adaptation strategy. These costs include the costs of adaptation and are the change in costs compared to a no climate change scenario—i.e., with infrastructure growth and baseline climate. For reference, without climate change, total annual expenditures for these infrastructure types would be about $95 billion/year in 2090, so an increase of $24 billion is about 25%higher. Annual impacts under the more extreme RCP8.5 scenario are roughly double those experienced under the lower emissions RCP4.5 scenario due to the much higher end-of-century temperature projections associated with RCP8.5. Moving from a strategy of No Adaptation to a Reactive or Proactive Adaptation strategy also roughly halves the expected costs of climate change experienced in 2090, with the proactive strategy providing larger reductions.

Fig. 3. The upper panel shows the annual average climate change costs (billions $2017/year) projected during the 2080 e 2099 period under the two emissions scenarios, three adaptation strategies and nine impact categories, averaged across the five GCMs. These totals include adaptation costs for the Reactive and Proactive Adaptation strategies. The lower panel displays the RCP8.5 emission results graphically. Results are organized from highest to lowest cost impact category. The numbering of each impact category corresponds to the numbering introduced in Table 1. Only eight of ten impact categories are shown here as impact category #2: Lightning on transmission lines and #5: Lightning on distribution lines are not associated with infrastructure damages, just interruption costs, as discussed in Section 4.

Looking more closely at the annual costs associated with each of the different stressor-response categories (Fig. 3), reductions in the lifespan of substation transformers and increases invegetation management expenditures represent the most costly impact categories, accounting for roughly 65% of costs under the No Adaptation strategy, under both emissions scenarios. These two impact categories are revisited in more detail in Section 3.3. The costs associated with the remaining stressor-response categories are less significant at the national scale, but can have a more pronounced effect regionally, as is found to be the case for wildfire damage and impacts to substations due to sea level rise and storm surge.

3.2. Evolution of infrastructure impactsover time

This section presents insights into how total CONUS-level impact costs evolve over time for the Reactive Adaptation strategy, as well as the uncertainty across the five GCMs used. Fig. 4 demonstrates that, as expected, the divergence between the two emissions scenarios and the five GCMs becomes increasingly more significant after 2050. The GCMs associated with the highest infrastructure impacts in 2090 indicate costs that are $11 billion/ year higher than those GCMs associated with median impacts in 2090. Note that under the Proactive Adaptation strategy, this high median difference decreases to only $6 billion/year, highlighting the importance of timely adaptation for reducing the magnitude as well as the variability of infrastructure impacts.

Fig. 4. Change in annual costs (billions $2017/year) across the five GCMs for 2030, 2050,2070, and 2090, under each of the climate emissions scenarios for the Reactive Adaptation strategy. Each boxplot contains 100 points made up of the five GCMs and 20 years within each era. The whiskers represent the 5th to 95th percentiles of these data, the boxes capture the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the filled and open circles are the mean and median across the data, respectively.

3.3. Spatial findings for the most costly infrastructure-impact categories

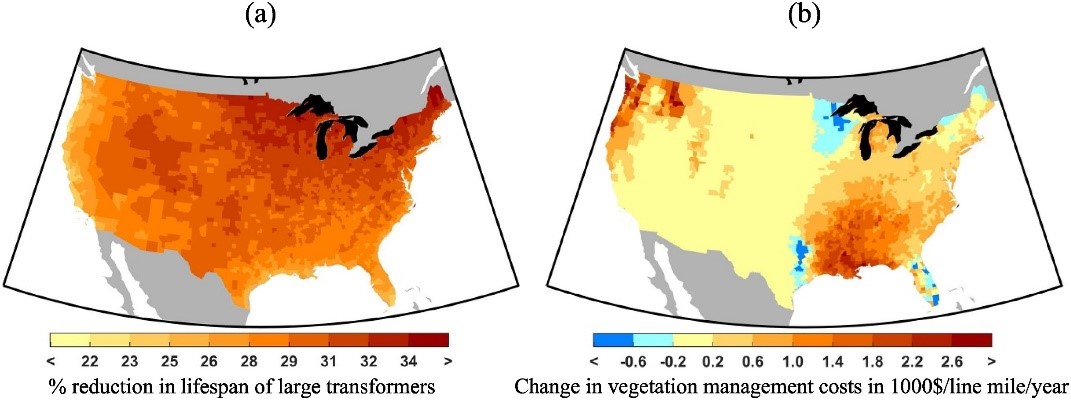

Section 3.1 noted that reductions insubstation transformer lifespan and increases in vegetation management costs represent the two most costly impact categories of the ten categories examined. This section revisits these two impacts, looking in more detail at their spatial distributions across the CONUS. Fig. 5a shows how the reduction in large substation transformer lifespan is highest in the Midwest and Northeast and lowest along the Gulf Coast and Western coast, as driven by higher and lower changes in temperature respectively. Fig. 5b displays how vegetation management costs increase overall in the Northwestern U.S. and in the East ofthe country, especially along the Gulf Coast, in response to extended growing seasons and/or precipitation levels. Conversely, costs decrease in parts of Florida, the Midwest and parts of Texas due to reductions in precipitation. Most of the West, excluding coastal and river waterways, where tree cover islow, shows little to no projected change in vegetation management costs.

Fig. 5. (a)Reduction in lifespan of large transformers (%) and (b) change in vegetation management costs ($ thousand/line mile/year) in 2090 as compared to the baseline for RCP 8.5, mean of all five GCMs.

3.4. Spatial findings for the ratio of annual impact costs to annual electricity sales

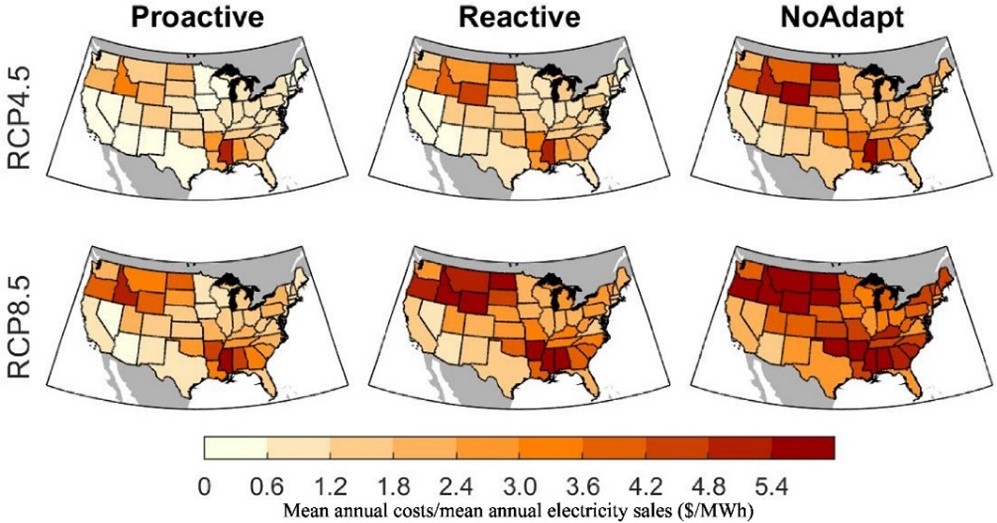

This section explores how the ratio of meanannual impact costs to mean annual electricity sales varies across the CONUS. This ratio gives an indication of the degree to which electricity costs could rise in the future if these impact costs are passed on to electricity consumers. Fig. 6 shows total annual end-of-century costs divided by electricity sales, with impacts varying from less than $0.5/MWh to upwards of$6/MWh. Although the large costs associated with impacts to large substation transformer lifespan are fairly constant across the country, the spatial pattern of changes in vegetation management show up as high $/MWh costs in the Northwest and Southeast, where vegetation management costs increase substantially. The high impacts in the central northern region of the country are driven by a relatively high ratio of grid infrastructure to electricity sales in those regions. It is unclear how much of these costs might be absorbed by the utility versus passed along to rate payers.

Fig. 6. The ratio of mean annual costs to mean annual electricity sales (units are $/MWh)projected during the 2080–2099 period across the two emissions scenarios and three adaptation strategies, averaged across the five GCMs. Data aggregated from the county to state level.

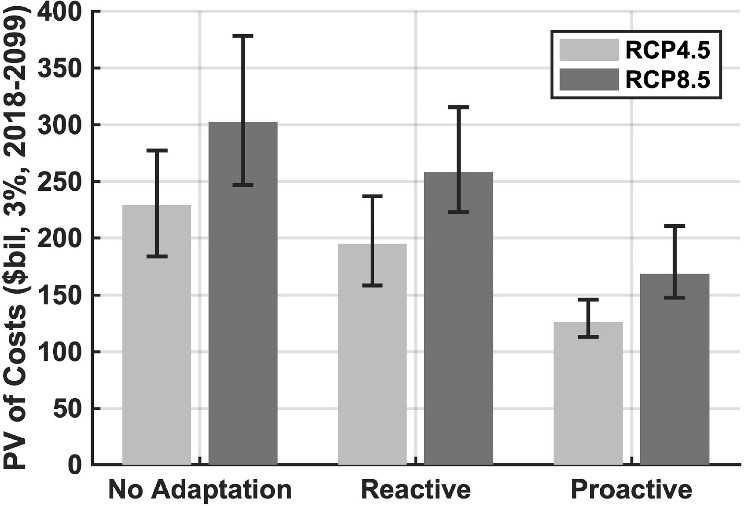

3.5. Net present value of total climatechange impacts from 2018 to 2099

Fig. 7. Net present value ($2017) of total CONUS-level costs, 2018–2099, discounted at 3%. Black line indicates the range of impacts across the five GCMs.

The net present value of total costs of climate change impacts across GCMs, emission scenarios, and adaptation strategies, ranges from $120 to $380 billion through 2099 (Fig. 7), when using a discount rate of 3%. The largest climate impacts occur after 2050, and these impacts are also the most heavily discounted. The effects of substantial discounting limit the difference between the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 emissions scenarios to about 20%, as compared to 50% cost differences seen in the undiscounted, end-of-century annual costs presented in Fig. 3. Looking across the different adaptation strategies, adaptation efforts do still have a profound effect on net present costs. Within a given emissions scenario, moving from a No Adaptation to a Proactive Adaptation strategy reduces net present costs by as much as 50%. (911 words)

Notes:

1. Table 1.