Reading A Methodological approach

Climate change impacts and costs to U.S. electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure

1.This study quantifies climate change impacts to electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure across the CONUS through a screening-level modelling analysis. Physical and economic impacts from damages to these infrastructure systems are estimated using stressor-response functions that relate different climate stressors to the response of the various relevant transmission and distribution infrastructure components. The analysis isevaluated for each of the 3109 counties in the CONUS.

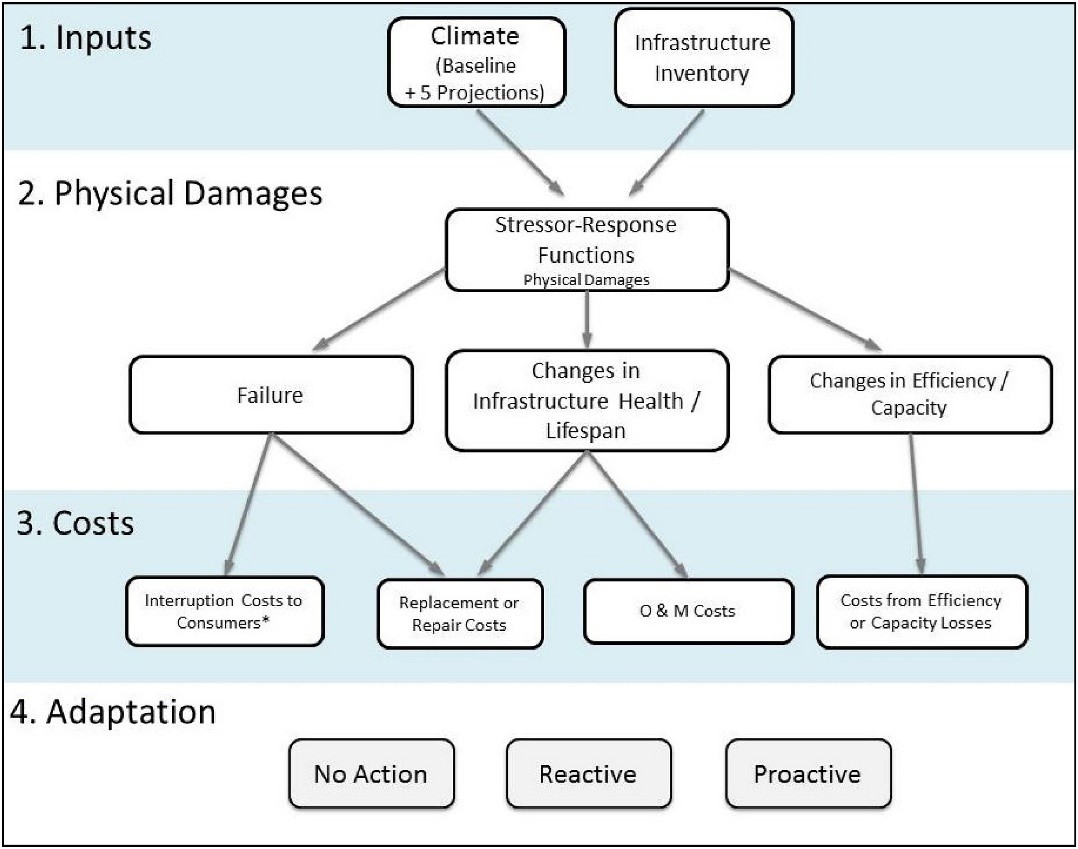

2.The overall steps of the screening-level analysis are shown in Fig. 1: first, climate inputs and an infrastructure inventory are supplied to our model. Second, physical damages to the infrastructure inventory are estimated using climate-driven stressor response functions. Third, economic impacts of these physical damages are quantified. Finally, the performance of different adaptation options is evaluated.

Fig. 1.Model Flow Diagram (*Note: Interruption cost approximations are presented in the discussion).

3.Model inputs (Step 1) are in the form of climate information from various GCMs and details of the energy infrastructure inventory in the U.S. Section 2.1discusses these inputs in more detail.

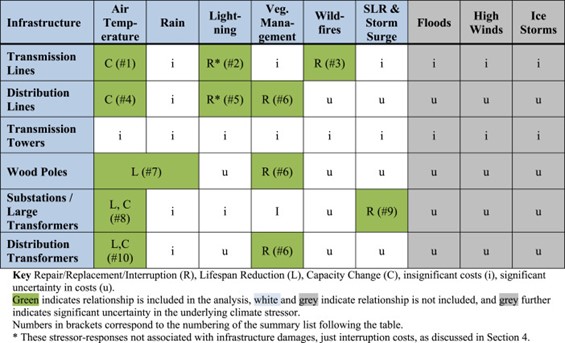

4.Estimation of physical damages to the inventory (Step 2), as represented by stressor-response functions, forms the heart of this analysis. We use process-based, engineering-type approaches to construct these stressor-response relationships (see Section 2.2). The stressor-response functions help determine the infrastructure’s physical “response” to climate stressors. These functions capture three different types of physical damage: (1) infrastructure can fail due to abrupt extreme events, resulting in power interruptions and/or necessitating repair or replacement; (2) infrastructure can deteriorate due to changes in wear and tear on the infrastructure caused by weather (i.e. lifespan reduction); and/or (3) climate can necessitate changes in transmission and distribution capacity (e.g., high ambient temperatures reduce the allowable current in power lines).

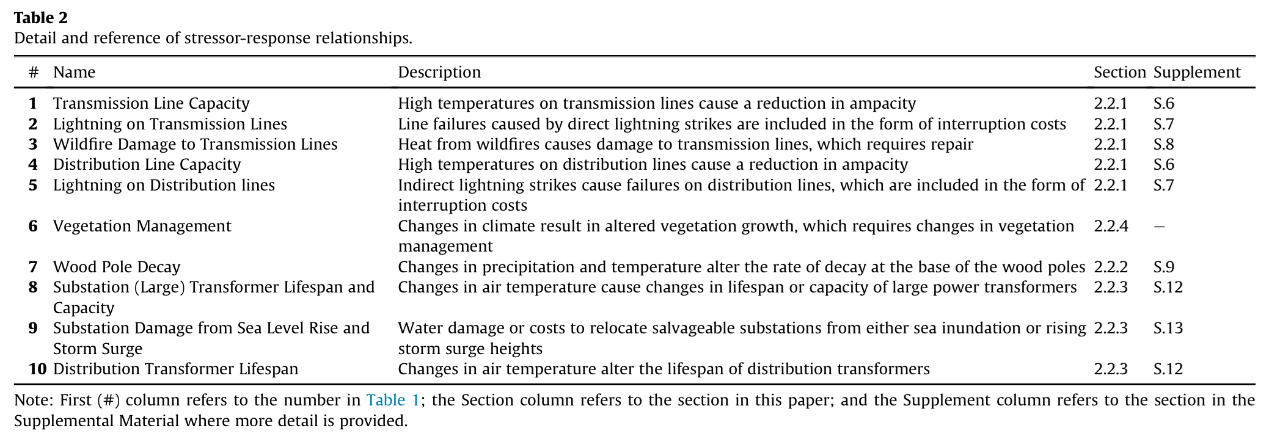

5.We do not include all possible climate change stressors, with many excluded because of insignificant associated costs (e.g., the impact of air temperature on transmission towers). Conversely, some relationships that are important forthe assessment of physical damages are necessarily excluded because the climate stressor is uncertain or the infrastructure damage estimation is too uncertain given the information available at the national-level. Notably, floods, highwinds (including hurricanes), and ice storms are excluded from this analysis, all of which are the most easily observable impacts to the electric grid, particularly the distribution system. These stressors are not included because even current state-of-the-art climate models represent these phenomena poorly due primarily to the coarse spatial scale of GCMs, as well as the complexity of representing extreme events such as hurricanes (where high winds and flooding cause major damage and power interruptions), convective storms (high winds), and ice storms. More detail on why these are excluded and potential changes in these stressors across the CONUS are provided in the Supplementary Materials(S.1, S.2 and S.3). Obviously, this is a sizable limitation of the analysis and excluding these types of damages likely changes the total climate change costs in a substantial way. However, without a clear direction as to how these phenomena change in the future, it is impossible to include these costs. These are identified as important areas for future research.

6.Table 1 shows the different stressor-response relationships considered in thisstudy: the green cells indicate those relationships that are included in the analysis, as well as the physical impact assessed (i.e. repair/replacement (R), lifespan reduction (L) and/or capacity change (C)), while the white and grey cells denote those excluded from the analysis either because the costs are insignificant (i) or too uncertain to estimate (u).

7.For ease of referring between this table and the results presented in Section3, each of the stressor-response relationships included in this analysis (i.e.each green cell in Table 1) is shown in Table 2, where the first column corresponds to the number in Table 1. For ease of reference, the “Section” column lists the section where these are described in this paper and the “Supplement” column lists the section in the Supplemental Material with additional detail.

These ten different physical infrastructure impacts are then translated to economic impacts by estimating the costs associated with identified damages (Step 3).Costs can be associated with the occurrence of interruptions, repair, replacement, operation and maintenance or loss of capacity. Section 2.3 discusses the process of cost estimation in more detail.

8.Utilities and policy-makers will respond to these physical and economic impactsin a variety of ways, which may dampen or exacerbate the impacts. Here, we donot predict or estimate their response. Instead, we examine three basic responses or adaptation scenarios to compare impacts given varying adaptation responses (Step 4). We use the term “adaptation” to mean any measure taken to lower the risks posed by changes in climate as opposed to “mitigation,” which is typically used in climate change science to refer to measures to reduce the amount and speed of future climate change by reducing emissions of GHGs.

9.The adaptation options considered are:

(1).No Adaptation: Utilities and policy-makers assume a stationary climate and continue to design to current observed climate. These impacts represent an upper bound of possible future impacts for the stressors included in this analysis.

(2).Reactive Adaptation: Utilities and policy-makers undertake adaptation once the damages or costs have been fully realized——and therefore react by upgrading design criteria.

(3).Proactive Adaptation: Utilities and policy-makers proactively consider the risks of climate change and are willing to pay the upfront costs of adaptation before any damages occur.

10.These adaptation scenarios are not meant to be probable scenarios i.e., it is unlikely that utilities and policy-makers will continue in business-as-usual through the end of the century as is depicted in the No Adaptation scenario. However, when replacing either damaged or retired infrastructure, utilities often replace “like with like”to avoid the need to redesign or re-permit. One of the key recommendations from the American Society of Civil Engineers’ Infrastructure Report Card is to streamline permitting, in part for this reason [20]. Section2.4 describes further details of these adaptation scenarios. (1002 words)

Notes:

1. Authors: CharlesFant, Brent Boehlert, Kenneth Strzepek, Peter Larsen, Alisa White, SahilGulati, Yue Li, Jeremy Martinich (2020). Climate change impacts and costs toU.S. electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure. Energy.

2. Keywords:Climate change; Infrastructure; Transmission; Distribution

3. Abstract: This study presents a screening-level analysis of the impacts of climate change onelectricity transmission and distribution infrastructure of the U.S. In particular, the model identifies changes in performance and longevity ofphysical infrastructure such as power poles and transformers, and quantifies these impacts in economic terms. This analysis was evaluated for the contiguousU.S, using five general circulation models (GCMs) under two greenhouse gasemission scenarios, to analyze changes in damage and cost from the baseline period to the end of the century with three different adaptation strategies.Total infrastructure costs were found to rise considerably, with annual climate change expenditures increasing by as much as 25%. The results demonstrate that climate impacts will likely be substantial, though this analysis only capturesa portion of the total potential impacts. A proactive adaptation strategy resulted in the expected costs of climate change being reduced by as much as 50% by 2090, compared to a scenario without adaptation. Impacts vary across the contiguous U.S. with the highest impacts in parts of the Southeast and Northwest. Improvements and extensions to this analysis would help better inform climate resiliency policies and utility-level planning for the future.

4. [20] AmericanSociety of Civil Engineers (ASCE). 2017 infrastructure report card: a comprehensive assessment of America’s infrastructure [Accessed April 2018],https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/2017-Infrastructure-Report-Card.pdf; 2017.