WATER MOVEMENT FROM THE LEAF TO

THE ATMOSPHERE

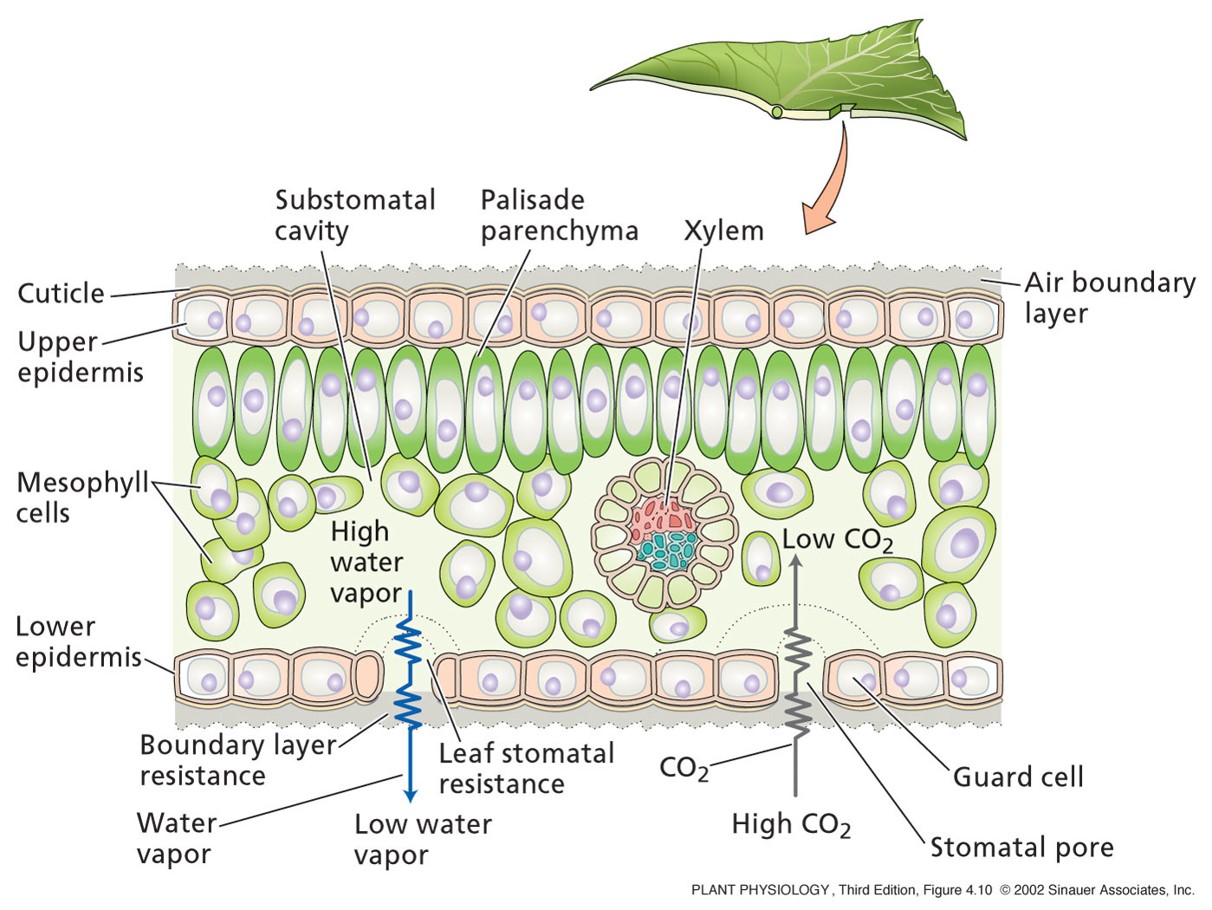

The Driving Force for Water Loss Is the Difference in Water Vapor Concentration

The difference in water vapor concentration is expressed as cwv(leaf) – cwv(air). The water vapor concentration of bulk air (cwv(air)) can be readily measured, but that of the leaf (cwv(leaf)) is more difficult to assess.

The Cell Walls of Guard Cells Have Specialized Features

Guard cells can be found in leaves of all vascular plants, they show considerable morphological diversity, but we can distinguish two main types: In grasses, guard cells have a characteristic dumbbell shape, with bulbous ends. In dicot plants and nongrass monocots, kidney-shaped guard cells have an elliptical contour with the pore at its center.

An Increase in Guard Cell Turgor Pressure Opens the Stomata

Guard cells function as multisensory hydraulic valves. Environmental factors such as light intensity and quality, temperature, relative humidity, and intracellular CO2 concentration are sensed by guard cells, and these signals are integrated into well-defined stomatal responses. If leaves kept in the dark are illuminated, the light stimulus is perceived by the guard cells as an opening signal, triggering a series of responses that result in opening of the stomatal pore.

Blue Light Activates stomatal opening

Blue light activate a proton pump in guard cell membrane. The acidification results from the activation by blue light of a proton-pumping ATPase in the guard cell plasma membrane that extrudes protons into the protoplast suspension medium and lowers its pH. In the intact leaf, this blue-light stimulation of proton pumping lowers the pH of the apoplastic space surrounding the guard cells.

Inward rectifier K+ channel is voltage dependent, PMhyperpolarization activates the channel and carry K+ inward

Cl- is transported through Cl- /H+symportor Cl-/OH- antiport

Potassium concentration in guard cells increases severalfold when stomata open, from 100 mM in the closed state to 400 to 800 mM in the open state. These large concentration changes in the positively charged potassium ions are electrically balanced by the anions Cl– and malate2–.