Chapter X Nerve System

The nervous system is divisible into a central component, consisting of the brain and spinal cord, and a peripheral component, consisting of nerve axons, dorsal root ganglia, and autonomic ganglia. The brain is divisible into: the brainstem (made up of the pons, medulla, and midbrain), the cerebellum, the diencephalon (made up of the thalamus and hypothalamus), and telencephalon (cerebral hemispheres). In the central nervous system, regions containing cell bodies are gray matter; those consisting of axons are white matter.

Functional Anatomy of Neurons

The basic unit of the nervous system is the nerve cell, or neuron. Dendrites and the cell body receive information from other neurons. The axon (nerve fiber), which may be covered with sections of myelin separated by nodes of Ranvier, transmits information to other neurons or effector cells.

Neurons are classified in three ways: Afferent neurons transmit information into the CNS from receptors at their peripheral endings. Efferent neurons transmit information out of the CNS to effector cells. Interneurons lie entirely with the CNS and connect afferent and efferent neurons. Information is transmitted across a synapse by a neurotransmitter, which is released by a presynaptic neuron and combines with receptors on a postsynaptic neuron. The CNS also contains glial cells, which sustain the neurons metabolically, form myelin, and serve as guides for the neurons during development.

Signal Transduction of Synapses

The signal from a pre- to a postsynaptic neuron is a neurotransmitter stored in synaptic vesicles in the presynaptic axon terminal and released into the synaptic cleft when the axon terminal is depolarized, thereby raising the calcium concentration within the terminal.

Depolarization of the synaptic terminal leads to an influx of Ca++, stimulating fusion of transmitter vesicles with the presynaptic membrane. Some of the neurotransmitter release and diffuses to the postsynaptic cell and are bound by receptor molecules on its surface. Receptor binding activates ion channels directly or by way of a G protein, leading to a change in the membrane conductance and a postsynaptic potential. The postsynaptic potential may summate with other synaptic inputs to increase or decrease the probability of an action potential in the postsynaptic cell. Excitatory (depolarizing) postsynaptic potentials result from an increase in conductance to all small cations; inhibitory postsynaptic potentials may be hyperpolarizing (resulting from an increase in K+ conductance) or silent (resulting from an increase in CL- conductance that stabilizes the membrane potential near its resting value). If the synapse is on another synaptic terminal, it can influence the synaptic efficacy of the second synapse, either increasing it (presynaptic facilitation) or decreasing it (presynaptic inhibition). Arrangement of neurons into circuits with appropriate synaptic connections makes the activity of postsynaptic cells depend on the inputs they get from presynaptic cells; this is the basis of neural integration in the nervous system.

The neurotransmitter diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to receptors on the postsynaptic cell, where they usually open ion channels. At an excitatory synapse the electrical response in the postsynaptic cell is called an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP). At an inhibitory synapse, it is an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP). Usually at an excitatory synapse, channels in the post-synaptic cell that are permeable to sodium, potassium and other small positive ions are opened; whereas at inhibitory synapses, channels to potassium and/or chloride are pened .The postsynaptic cell's membrane potential is the result of temporal and spatial summation of the EPSP and IPSP at the many active excitatory and inhibitory synapses on the cell.

Neuroeffector Communication The junction between a neuron and an effector cell is called a neuroeffector junction. The events at a neuroeffector junction release of transmitter into an extracellular space, diffusion of transmitter to the effector cell, and binding with a receptor on the effector cell are similar to those at a synapse.

Receptor Receptors translate information from the external world and internal environment into graded potentials, which then generate action potentials. Receptors may be either specialized endings of afferent neurons or separate cells adjacent to the neurons. Receptors respond best to one form of stimulus energy, but they may respond to other energy forms if the stimulus intensity is abnormally high. Regardless of how a specific receptor is stimulated, activation of that receptor always leads to perception of one sensation. Application of a stimulus to a receptor opens ion channels in the receptor membrane. Ions then flow across the membrane, causing a receptor potential. Receptor potential magnitude and action potential frequency increase as stimulus strength increases. Receptor potentials can be summed.

Somatic Sensation

Sensory function of the skin and underlying tissues is served by a variety of receptors sensitive to one (or a few) stimulus types. Information about somatic sensation enters both specific and nonspecific ascending pathways. The specific pathways cross to the opposite side of the brain. The somatic sensations include touch-pressure, proprioception and kinesthesia, temperature, and pain. Some mechanoreceptors of the skin are rapidly adapting and give rise to sensations such as vibration, touch, movement, and tickle, whereas others are slowly adapting and give rise to the sensation of pressure. Skin receptors having small receptive fields are involved in fine spatial discrimination, whereas receptors having larger receptive fields signal less precise touch/pressure sensations. The major receptor type responsible for proprioception and kinesthesia is the muscle-spindle stretch receptor. Cold receptors are sensitive to decreasing temperatures; warm receptors signal information about increasing temperature. Specific receptors give rise to the sensation of pain, which may induce emotional and reflex responses as well as the perception of pain. Stimulation-produced analgesia and TENS control pain by blocking transmission in the pain pathways. Temperature and pain are sensed by free nerve endings. The dorsal columns of the spinal cord are labeled lines that carry sensory pathways to specific cortical processing regions. The nonspecific pathway exercises a general arousal effect on the brain by way of the reticular activating system.

Neural pathways in sensation A single afferent neuron with all its receptor endings is a sensory unit. The area of the body that, when stimulated, causes activity in a sensory unit or other neuron in the afferent pathway is called the receptive field for that neuron. The specific ascending pathways convey information about only a single type of information to the cerebral cortex. Nonspecific ascending pathways convey information from more than one type of sensory unit to the brainstem reticular formation and regions of the thalamus not part of the specific ascending pathways.

Regulation of Motor Function

The neural systems that control body movements are arranged in a motor control hierarchy. The highest level determines the general intention of an action. The middle level specifies the postures and movements needed to carry out the intended action and, taking account of sensory information that indicates the body's position, establishes a motor program. The lowest level determines which motor neurons will be activated. As the movement progresses, information about what the muscles are doing is fed back to the motor control centers, which make any needed program corrections. Actions are voluntary when we are aware of what we are doing and why or when we are paying attention to the action or its purpose. Almost all actions have conscious and unconscious components.

Local control of motor neurons Somatic motor neurons project directly to skeletal muscle fibers, innervating each muscle fiber with a single excitatory synapse. Most input to motor neurons arises from local interneurons, which themselves receive input from peripheral receptors, descending pathways, and other interneurons. Muscle length and changes in length are monitored by muscle spindle stretch receptors. Activation of these receptors initiates the stretch reflex, in which motor neurons of ipsilateral antagonists are inhibited and those of synergists are activated. Tension on the stretch receptors is maintained during muscle contraction by gamma efferent activation of the spindle muscle fibers. Alpha and gamma motor neurons are often coactivated. Muscle tension is monitored by Golgi tendon organs, which inhibit motor neurons of the contracting muscle and stimulate ipsilateral antagonists. The flexion reflex excites the ipsilateral flexor muscles and inhibits the ipsilateral extensors. The crossed-extensor reflex excites the contralateral extensor muscles during excitation of the ipsilateral flexors.

Spinal segmental reflexes that contribute to posture, protection, and voluntary movement include (1) the stretch reflex, which maintains muscle length constant; (2) the withdrawal reflex, which mediates rapid flexion of an injured limb; (3) the crossed extension reflex, which extends the limb contralateral to a flexed limb; and (4) the Golgi tendon reflex, which may protect muscles and their tendons from extremes of tension.

Motor programs may be generated at several levels in the central nervous system. Simple stepping can be carried out by the spinal cord. More complicated motor programs require the participation of the basal ganglia, motor cortex, and cerebellum. The cell bodies of motor neurons in spinal cord segments are arranged so that distal muscles are served by lateral motor neurons and medial motor neurons control proximal muscles. Pathways from the motor centers of the brain to spinal motor neurons can be divided roughly into two categories: one class that serves primarily proximal muscles and mainly mediates adjustments of posture, and one that serves distal muscles and is important for fine movements. Control of distal muscles is exerted mainly by the direct corticospinal (pyramidal) tract; control of proximal muscles involves polysynaptic (extrapyramidal) tracts that pass through brainstem nuclei.

Descending pathways and the brain centers that control them The location of the neurons in motor cortex varies with the part of the body the neurons serve. A readiness potential is fired from the supplementary motor area 800 ms. before any electrical activity in motor cortex begins. This is followed by a motor potential in motor cortex. The basal ganglia help determine the direction, force, and speed of movements. The cerebellum coordinates posture and movement. The pathways pass directly from the sensorimotor cortex to motor neurons in the corticospinal spinal cord (in the brainstem, in the case of the corticobulbar pathways) or to interneurons near the motor neurons. In general, neurons on one side of the brain control muscles on the other side of the body. Corticospinal pathways serve predominantly fine, precise movements. Some corticospinal fibers affect the transmission of information in afferent pathways. The multineuronal pathways consist of chains of neurons that carry information from the sensorimotor cortex, basal ganglia and other subcortical nuclei, cerebellum, and brainstem nuclei to motor neurons in the brainstem or spinal cord or interneurons near them. Some fibers loop back to alter earlier pathway components. The multineuronal pathways are involved in the coordination of large groups of muscles used in posture and locomotion. There is some duplication of function between the two descending pathways.

Muscle tone Muscle tone is due to the viscoelastic properties of muscles and joints and to any ongoing contractile activity.

Maintenance of upright posture and balance To maintain balance, the body's center of gravity must be maintained over the body's base. Postural reflexes depend on inputs from eyes, vestibular apparatus, and proprioceptors. The stretch and crossed extensor reflexes are postural reflexes.

Functions of Autonomic Nervous System

The preganglionic neurons whose cell bodies are in the central nervous system synapse in peripheral ganglia with postganglionic fibers that innervate visceral effectors. The parasympathetic and sympathetic branches of the autonomic motor system differ anatomically in that the ganglia in the sympathetic branch are anatomically remote from the effector organs, while the ganglia of the parasympathetic branch are located in or on the effector organs. Visceral effectors typically have dual innervation by autonomic fibers from both the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches and may possess more than one motor synapse on each effector cell. As a general rule of organization of the motor systems, the transmitter chemical at the first synapse outside the nervous system is acetylcholine.

The responses of visceral effectors to autonomic inputs are mediated by pharmacologically distinguishable types of receptor molecules. Nicotinic cholinergic receptors are located on autonomic postganglionic cells of both branches, but muscarinic receptors are found on effectors innervated by cholinergic postganglionic fibers. Adrenergic receptors are divided into a and B types, and into a1, a2, B1and B2 subtypes. The subtypes are typically associated with particular effectors, although some effectors have more than one subtype. For any given tissue, the effect of autonomic inputs depends entirely on the second messenger systems activated by transmitter-receptor binding; the same receptor subtypes can frequently mediate opposite responses in different tissues.

States of Consciousness and Emotion

States and experiences of consciousness Electric currents in the cerebral cortex due predominately to summed postsynaptic potentials are recorded as the EEC. Slower EEG waves correlate with less responsive behaviors. Rhythm generators in the thalamus are probably responsible for the wavelike nature of the EEG. Alpha rhythms and, during EEG arousal, beta rhythms characterize the EEG of an awake person. Sleep is an activity of the brain. It can be divided into slow-wave sleep and REM sleep on the basis of differences in the EEC, muscle tone, and arousability .Slow-wave sleep progresses from stage I (faster, lower-amplitude waves) through stage 4 (slower, higher-amplitude waves), followed by an episode of REM (paradoxical) sleep. There are generally five of these cycles per night .In the brainstem, a sleep producing system and an arousal system interact to produce sleep-wake cycles. Brain structures involved in directed attention, particularly the locus ceruleus, are thought to determine which areas of the brain gain temporary predominance in the ongoing stream of conscious experience. It is believed that conscious experiences, which depend on directed attention, occur because of activity in interacting neuron networks. In order for conscious experiences to occur, neural activity must be present in the brain for a minimum period of time. Neural processes that result in perceptions, judgments, problem solving ability, and discriminative responses to stimuli can occur even though conscious experiences do not develop.

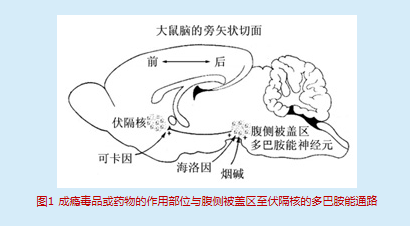

Emotion Behaviors that satisfy homeostatic needs are primary motivated behaviors. Behavior not related to homeostasis is a result of secondary motivation. Repetition of a behavior indicates appetitive motivation. Avoidance of a behavior indicates aversive motivation. Lateral portions of the hypothalamus are involved in appetitive motivation. Norepinephrine, dopamine, and enkephalin are transmitters in the brain pathways that mediate appetitive motivation and reward. Two aspects of emotion, inner emotions and emotional behavior, can be distinguished. Different brain areas mediate these two aspects of emotion, but both aspects work together so that the behaviors truly represent the inner emotions. The limbic system integrates inner emotions and behavior.

Learning and Memory

Motivations (rewards and punishments) are generally crucial to learning. Working memory has limited capacity, is short term, and depends on functioning brain electrical activity. After registering in working memory, facts either fade away or are consolidated in long-term memory, depending on attention, motivation, and various hormones. Long-term memory, of which there are two forms procedural and declarative seems to have an unlimited capacity and to be independent of brain electrical activity. Memory traces are localized, discrete brain areas containing cellular or molecular changes specific to different memories. Learning is enhanced after subjects are exposed to enriched environments. The enhancement is presumably due to the brain neural and chemical development that follows such exposure. Learning occurs when sensory inputs result in altered behavior. The behavior alteration may involve responses to repeated stimuli (habituation and sensitization) or induction of a response to a neutral stimulus (associative learning). Information may be stored in verbal and nonverbal forms, and it is not possible to identify a single discrete brain region in which memory stores are located. Short-term memory depends on electrical activity in neuronal circuits. In simple nervous systems, long-term storage appears to involve a change in synaptic responsiveness that requires protein synthesis. In the course of development, the dominant hemisphere differentiates a specialization for control of voluntary motor activities and language. Usually the left hemisphere becomes dominant. The non-dominant hemisphere differentiates a specialization for nonverbal intellectual functions. Damage to language regions of the dominant hemisphere results in aphasias (language disabilities) and impairments of verbal memory. Damage to corresponding regions of the nondominant hemisphere results in impairment of spatial and nonverbal functions.

Cerebral Dominance and Language

The two cerebral hemispheres differ anatomically, chemically, and functionally. In 90 percent of the population, the left hemisphere is superior at producing language and in performing other tasks that require rapid changes over time.