Chapter 5 Exchange Rate Systems

Unit 3

LEARNING OUTCOMES 学习效果:

understand cost cutting strategies of manufacturers in response to currency appreciation

examine the benefits and drawbacks of fixed system

identify the background and concepts of Bretton Woods System

FOCUS AND DIFFICULTIES 知识重难点:

Focus: cost cutting strategies of Japanese manufacturers in response to yen's appreciation, benefits and drawbacks of fixed system, background and concepts of Bretton Woods System

Difficulty: causes of Japanese yen appreciation against dollar

LECTURE VIDEO 授课视频:

LEARNING OUTLINE 学习大纲:

1. Cost Cutting Strategies of manufacturers in Response to Currency Appreciation

Recall that: Appreciation of home currency raises the relative costs of the nation's firms and thus reduces the international competitiveness of its exporting goods.

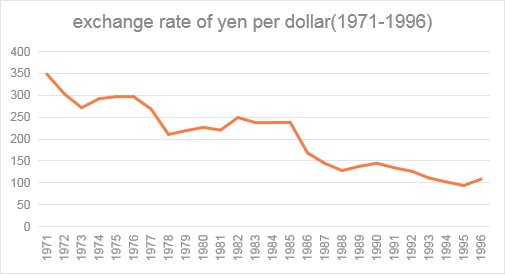

In 1990s, Japan experienced a persistent increase on the value of Japanese yen relative to US dollar.

a. Causes of Yen's appreciation relative to $:

(1)Japan's economic strength was growing relative to that of the United States.

In the early post-war period, Japan implemented the "dodge Line", which eradicated the serious inflation. The economy began to recover, and with a series of financial system reforms, the foundation of economic development was strengthened.

In 1950s to 1970s, Japan's economic growth rate remains above 10% per year on average, with a strong investment demand, a rising productivity growth, growing exports and a lower inflation rate relative to U.S..

In terms of industrial structure, Japan has adapted to changes in domestic and foreign conditions, improved its industrial structure, and constantly established competitive industrial sectors. These factors have made Japan a major producer of home appliances, automobiles and semiconductors in the international market, leading to a large trade surplus.

The oil crisis in 1970s had an important impact on the whole western world. With the increase of production cost, stagflation of different degrees occurred in the United States, Japan and other western countries.

Japan, which relies heavily on energy imports, was particularly hard hit, with double-digit inflation in 1973-75. But the impact of the oil shock was mitigated by rapid adjustments in Japan's industrial policy, which overcame the adverse impact of higher oil prices in a short period of time by improving energy technologies and producing fuel-efficient cars. The Improvement of industrial structure allowed Japan to eliminate the impact of oil shock and recover the economy quickly.

Since 1990, Japan's bubble economy has burst rapidly and its financial assets have been greatly reduced, which has brought a massive blow to Japan's real economy. Japan's initial advantage in economic growth has disappeared.

However, the relative economic strength of the United States and Japan has not changed fundamentally.

(2)Persistent huge surplus on currenct account balance of Japan

In 1980s, Japan experienced Persistent huge surplus on currenct account balance; as a result, Japan's stock of foreign assets increased rapaidly, become the largest creditor in the world, which inevitably pushed up the exchange value of Yen against dollar.

(3)Intervention by western countries and political pressure

The U.S., European union and other trading partners strongly unsatisfied with Japan's huge trade surplus. The western countries believed that the yen exchange rate was too low and decided to intervene by selling dollars in the foreign exchange market jointly.

They signed the Plaza Accord in 1985 to weaken the dollar against the yen in order to reverse the serious trade imbalance between the western countries and Japan.

So, since then, the yen appreciated against dollar by 50% within three years.

Such a persistent appreciation of yen against dollar cause Japanese goods to become less competitive in world markets and makes it harder for Japanese manufacturers to profit out of exports.

b. How did they respond to the impacts of yen’s appreciation on dollar production costs and dollar prices of Japanese export goods?

(1) Japanese manufacturers establish integrated manufacturing bases in the U.S. and in dollar-linked Asia where the dollar depreciates relative to yen..

This strategy allows Japanese firms to use strong yen to purchaser cheaper dollar denominated components and materials from around the world and assemble them where the labor cost was lower, in order to offset the rising costs of domestic inputs.

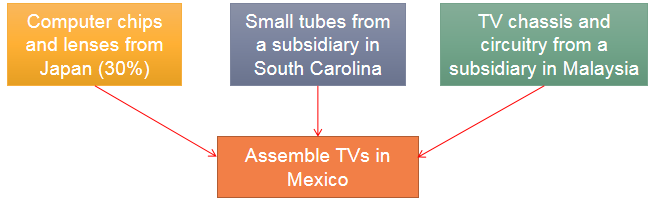

Consider the Japanese electronoic manufacturer Hitachi.

In the mid-1990s, as the yen appreciated against the dollar, Hitachi's global diversification permitted it to sell TVs in the U.S. without raising prices.

In particular, the small tubes came from a subsidiary in South Carolina, denominated in dollars. And, TV chassis and circuitry came from a subsidiary in Malaysia, denominated in dollars. While, only computer chips and lenses came from Japan that amounted to 30% of the value of the parts used in one TV set. In the end, another Hitachi's subsidiary in Mexico assembled the TVs, where the assembling costs such as labor costs were denominated in peso which depreciated against dollar.

Therefore, by sourcing TV production in countries whose curerncies had fallen against the yen, Hitachi was able to remain the dollar price of its TV sets despite the rising yen so as to maintain its market share in US market.

(2) To limit their vulnerability to a rising yen, Japanese manufacturers shifted production from commodity-type goods to high-value products.

Because commodity-type goods (such as metals and textiles) are quite sensitive to price changes so that customers could easily switch to non-Japanese producers who charge lower dollar price for same products.

While, more sophisticated, high-value products—such as transportation equipment and electrical machinery—are less sensitive to price changes so that even if the dollar price of those Japanese products rises, customers are less incentive to switch in short run.

Consider the Japanese auto industry.

To offset the rising yen, Japanese automakers cut the yen prices of their cars and thus experienced falling unit-profit margins.

Meanwhile, they reduced manufacturing costs by improving worker productivity, importing materials and parts whose prices were denominated in depreciating currencies against yen, and outsourcing larger amounts of a vehicle’s production to transplant factories in countries whose currencies depreciated against yen.

For example, Toyota corporation cut costs at full stretch by pressuring Japanese suppliers to lower part prices, adopting standardized methods to produce vehicles, reintroducing foreign made parts inferior but cheaper to domestically produced parts , and setting up manufacturing bases in Southeast Asia and South America.

2. Advantages and Disadvantages of fixed exchange rate system

Fixed ex-rate systems tend to be used primarily by small, developing nations whose currencies are anchored to a key currency.

Fixed ex-rate system provides several benefits for developing countries.

Under a fixed ex-rate system, governments stabilize the value of a currency by directly fixing its value in a predetermined ratio to a key currency or a currency basket.

In doing so, the more stability of ex-rates makes international trade and investments easier and more predictable, especially useful for small economies which borrow primarily in foreign currency, and in which the external trade forms a large part of their GDP. And, a fixed rate largely eliminates the exchange rate movements and thus reduces the sepculation which would causes huge market fluctuations.

A fixed rate reduces the ex-rate risks, facilitating the cost accounting of exports and imports as well as the evaluation on profitability of international investment projects.

In addition, stabilizing the ex-rate against a key currency of which country has relatively low inflation (like peg against dollar and the U.S. has a relatively low inflation), can help reduce the nation's inflation.

Drawbacks:

To defend a fixed rate, it would destory the internal balance for a nation. For instance, a defict nation tends to have a depreciating currency. To defend its fixed rate, the government may adopt a contractionary fiscal or monetary policy, which would lead to lower output and higher unemployment. On the other side, a surplus nation tends to have an appreciating currency. To defend its fixed rate, the government may adopt an expansionary fiscal or monetary policy, which would lead to high inflation.

When the balance-of-payments deficit creates downward pressure on the currency value, the government need intervene by selling foreign currencies in foreign exchange market, so as to stabilize the exchange value of its home currency. Thus, it requires a large holdings of foreign currency reservs to support the nation's currency.

A fixed rate is vulnerable to speculative attacks. For instance, there always exists a large number of short speculators who seek chance to short a company's stock or a country's currency under a fixed exchange rate arrangement. At first, the speculators would sell out their holdings of the nation's currency and trumpet the country's financial and currency instability to cause investors' worries about their investments in this nation, thus resulting in downward pressure on the currency's value. Initially, the nation's government would use its holdings of reserves to sell dollars and buy home currency, in order to maintain its fixed rate. But, the copycat effect caused by Market panic will lead to further depreictaion on the nation's currency. In the end, the government was unable to support the initial official rate and had to declare the currency devaluation. And, at that time, the speculators could earn huge profits from the sharp devaluation of that currency.

This story repeated many times in the history, like the Thai baht crisis in 1997.

3. Bretton Woods System

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, countries attempted to shore up their failing economies by sharply raising barriers to foreign trade, devaluing their currencies to compete against each other for export markets, and curtailing their citizens' freedom to hold foreign exchange. These attempts proved to be self-defeating. World trade declined sharply and employment and living standards plummeted in many countries.

So, member countries realized the unstatisfactory monetary experience with the gold standard and unsuccessful experimenting with floating exchange rates and exchange controls.

This breakdown in international monetary cooperation led the IMF's founders to plan an institution charged with overseeing the international monetary system—the system of exchange rates and international payments that enables countries and their citizens to buy goods and services from each other. The new global entity would ensure exchange rate stability and encourage its member countries to eliminate exchange restrictions that hindered trade.

The IMF was conceived in July 1944, when representatives of 45 countries meeting in the town of Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in the northeastern United States, agreed on a framework for international economic cooperation, to be established after World War II.

The countries that joined the IMF between 1945 and 1971 agreed to keep their exchange rates (the value of their currencies in terms of the U.S. dollar and, in the case of the United States, the value of the dollar in terms of gold) pegged at rates that could be adjusted only to correct a "fundamental disequilibrium" in the balance of payments, and only with the IMF's agreement. This system was known as the Bretton Woods system that would draw on the lessons of the previous gold standards and the experience of the Great Depression and provide for postwar reconstruction.

Member countries settled international balances in dollars, and US dollars were convertible to gold at a fixed exchange rate of $35 an ounce. The United States had the responsibility of keeping the price of gold fixed and had to adjust the supply of dollars to maintain confidence in future gold convertibility.

The Bretton Woods system was in place until persistent US balance-of-payments deficits led to foreign-held dollars exceeding the US gold stock, implying that the United States could not fulfill its obligation to redeem dollars for gold at the official price.

In August 1971, the U.S. government suspended the convertibility of the dollar (and dollar reserves held by other governments) into gold.

Since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, IMF members have been free to choose any form of exchange arrangement they wish (except pegging their currency to gold): allowing the currency to float freely, pegging it to another currency or a basket of currencies, adopting the currency of another country, or forming part of a monetary union like European monetary union.

4. Adjustable Pegged exchange rates

IMF founders realized that neither completely fixed nor floating rates were optimal; instead they adpoted a kind of semi-fixed rate system, known as adjustable pegged ex-rates in which a currency is pegged or fixed to a major currency such as the U.S. dollar or euro but can be readjusted to account for changing market conditions.

Member nations could re-peg its ex-rate via devaluation or revaluation policies, to reverse a persistent payments imbalance.

Market ex-rates were almost fixed, being kept within a band of 1% above or below the par value.

If the exchange rate moves by more than the agreed upon level, the central bank intervenes to maintain the band limits.

5. The Crawling Peg

The crawling peg system means that a nation makes small, frequent changes in the par value of its currency to correct a BOP disequilibrium.

The crawling peg has been used primarily by nations with high inflation rates. Instead of fixed or floating rates, the crawling peg provides a compromise approach to combine the flexibility of floating rates with the stability usually associated with fixed rates.

The crawling peg differs from the adjustable peg. Under the adjustable peg, a par value changes infrequently (perhaps once every several years) but suddenly, usually in large numbers. While, under the crawling peg, a par vaule chenges serveral times a year with small creeps.

6. Currency manipulation

Currency manipulation is the purchase or the sale of a currency on the exchange market by the fiscal authority or monetary authority, in order to influence the value of that currency.

For instance, by selling yen and buying dollars, Japan can depreciate its yen against dollar. A depreciating yen can make Japanese exports cheaper and encourages American factories to move to Japan, thus fostering Japan's economic growth internally. However, it is bad for U.S. since U.S. exports to Japan decreases and U.S. imports from Japan increases.

The U.S. government has complained countless times about being the victim of deliberate currency manipulation by its trading partners who are trying to steal demand away from their American competitors. And U.S. Congress proposed many bills that placed sanctions on currency manipulators.

So, we can see that lowering a country’s ex-rate can make its exports cheaper and fosters growth internally. That only causes problems for other countries because one currency can fall only of another rises.

This imbalance could spark a currency war—a destabilizing battle where countries compete against one another to get the lowest ex-rate.

7. Currency Crises

A currency crisis also called speculative attack, is a situation in which a weak currency experiences heavy selling pressure.

There are serveral possible indications of selling pressure.

One is sizeable loseese in the holdings of foreign reserves by the country's central bank.

Second is depreciating exchange rates in forward market.

Third is widespread flight out of domestic currency into foreign currency.

Currency crisis can decrease growth of GDP by 6% or more.