Chapter 5 Exchange Rate Systems

Unit 2

LEARNING OUTCOMES 学习效果:

understand how to achieve market equilibrium under floating rates

identify the nature and operation of a managed float

explain how the central bank stabilize the temporary exchange rates under a managed float

FOCUS AND DIFFICULTIES 知识重难点:

Focus: distinguish the concepts of floating rates and fixed rates, understand the concept of a managed float

Difficulty: explain the managed float in the short run and long run, explain how to intervene in foreign market and adopt monetary policies to stabilize the ex-rates in short run under a managed float

LECTURE VIDEO 授课视频:

LEARNING OUTLINE 学习大纲:

1. Floating Exchange Rates

Under floating exchange rates, market forces of supply and demand determine currency values. Currency prices are established daily in the foreign-exchange market without restrictions imposed by government policy.

So, unlike fixed ex-rates, floating exchange rates don't have par values and official ex-rates, and don't have an exchange stabilization fund to maintain stable rates.

Under floating exchange rates, central banks can conduct an independent monetary policy to improve economic performance and hold international reserves aiming at promote trade balances rather than defend any fixed ex-rates.

Achieving Market Equilibrium under floating rates

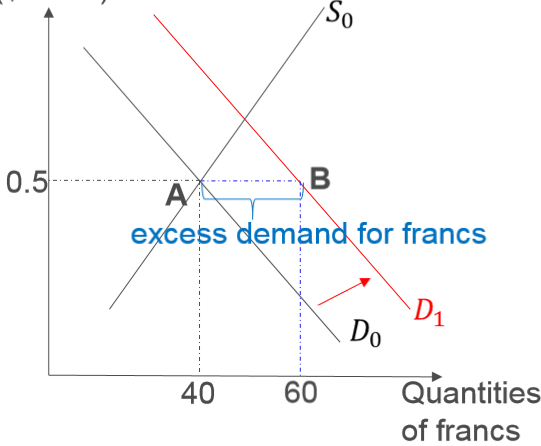

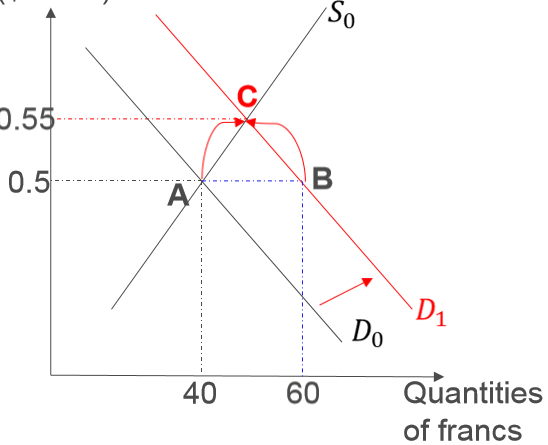

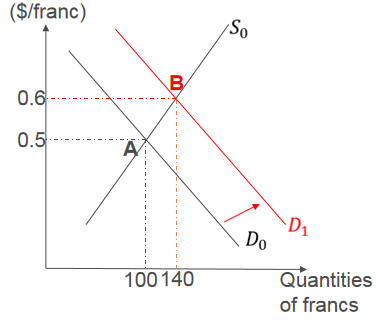

Starting with equilibrium point A: ER($/SFr)=$0.50/franc, S0 and D0 intersected.

(1) Suppose now U.S. imports more Swiss products, raising demand for francs from D0 to D1;

So, at the rate of $0.50/franc, the quantity of franc demanded exceeds the quantity of franc supplied.

The excess demand for francs raises the ex-rate from $0.50/franc to $0.55/franc, which indicate the dollar depreciate relative to franc while franc appreciates relative to dollar.

In the end, market equilibrium is restored at $0.55/franc where the quantity of franc demanded and supplied are equal.

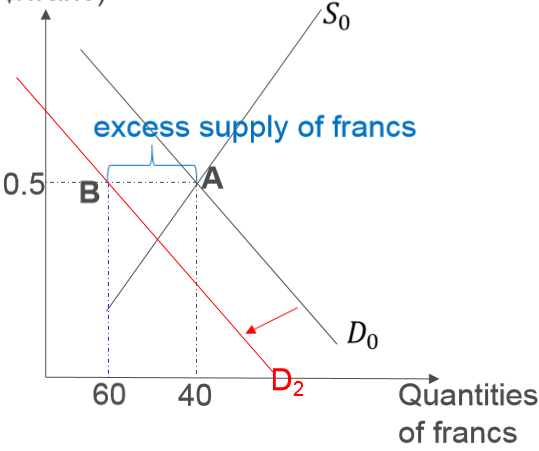

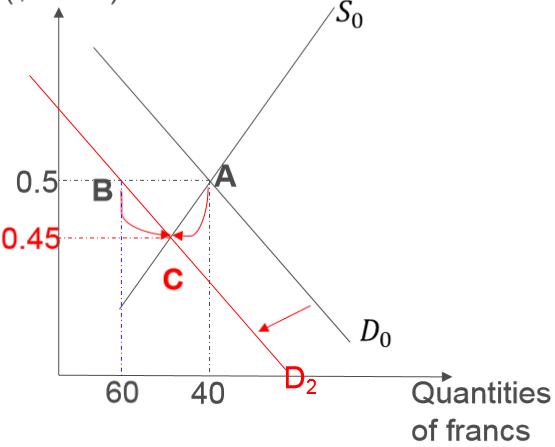

(2) Suppose now U.S. imports less Swiss products, reducing demand for francs from D0 to D2;

So, at the rate of $0.50/franc, the quantity of franc supplied exceeds the quantity of franc demanded.

The excess supply of francs decreases the ex-rate from $0.50/franc to $0.45/franc, which indicate the dollar appreciate relative to franc while franc depreciates relative to dollar.

In the end, market equilibrium is restored at $0.45/franc where the quantity of franc demanded and supplied are equal.

Conclusion:

In response to market forces, floating exchange rates can adjust freely to restore market equilibrium where the quantity of foreign exchange demanded and supplied are equal.

If the exchange rate promotes market equilibrium, monetary authorities will not need international reserves for the purpose of intervening in the market to maintain exchange rates at their par value.

Insteadly, these resources can be used to produce other goods or services in the economy.

Do import restrictions lead to increasing total employment in the economy?

Suppose the U.S. increases tariffs on chemicals imported from China, to protect its local chemical industry.

This policy would reduce chemicals imports and induce U.S. residents to purchase from the competing local chemical producers. Thereby, the sales and employment in U.S. chemical industry will be improved.

A decrease on chemical imports would cause a decrease in the U.S. demand for Chinese yuan to pay for imported chemicals.

With floating exchange rates, the dollar would appreciate against the yuan.

The dollar's appreciation against Chinese yuan would ecourage Americans to purchase more children's toys from China meanwhile Chinese to purchase fewer pork products from U.S.

As a result, both the competing toy industry and the exporting pork producers in U.S. will lose sales and employment.

So, When the U.S. restrict chemicals imported from China, job increases in chemical industry are offset by job decreases in toy industry and pork producers in the U.S. economy.

It is a zero sum game with floating ex-rates.

Arguments for floating exchange rates:

One advantage for floating rates is their simplicity. Floating rates respond quickly to changing supply and demand conditions, clearing the market of shortages or surpluses of a given currency.

Floating rates operate under simplified institutional arrangements that are relatively easy to implement.

Because floating rates fluctuate throughout the day, they permit continuous adjustment in the balance of payments. Under the floating exchange rate system, the speed of promoting the balance of payments equilibrium through exchange rate adjustment is faster than the adjustment process under the fixed exchange rate system.

With the help of floating ex-rates, the governments will not have to restore payments equilibrium through painful adjustment policies. Nations have greater freedom to pursue policies that promote domestic balance.

Moreover, floating rates allow governments to set independent fiscal and monetary policies and reduce the need for international reserves.

Arguments against floating exchange rates:

An unregulated market may lead to wide fluctuations in currency values, increasing the cost of hedging for international traders and investors and thereby discouraging foreign trade and investment.

The floating rates may cause another problem: inflationary bias. Under a floating system, monetary authorities may lack financial discipline. A nation with a relatively higher inflation rate tends to have a depreciating currency. Under a floating system, the freely depreciation of the nation's currency would result in persistenly increasing import prices and a rising price level.

And, there is greater freedom for domestic financial management, thus might induce overspending in government budgets.

2. Managed Floating Rates

In 1973 followed the breakdown of the Bretton Woods System, the U.S. and other industrial nations adopted the managed floating ex-rates, under which informal guidelines were established by the IMF for coordination of national ex-rate policies.

Under managed floating, a nation can alter the degree to which it intervenes in the foreign-exchange market. Heavier intervention makes the nation closer to a fixed rate, whereas less intervention makes the nation closer to a floating rate.

According to IMF guidelines, member nations should intervene in the foreign exchange market as necessary to prevent sharp and disruptive exchange rate fluctuations. Such a policy is known as leaning against the wind, intervening to reduce short-term fluctuations in exchange rates regardless of any long-run equilibrium ex-rate.

Under managed float, some nations choose target ex-rates and intervene to support them. Target ex-rates are intended to reflect long-term economic forces that underlie exchange rate movements.

Managed floating rates attempt to combine market determined ex-rates with foreign exchange market intervention in order to take advantage of the best features of floating and fixed ex-rate systems.

In particular, under a managed floating, market intervention is used to stabilize exchange rates in the short term; in the long run, a managed floating allows market forces to determine exchange rates.

The theory of a managed float in a two-country world: Switzerland and U.S.

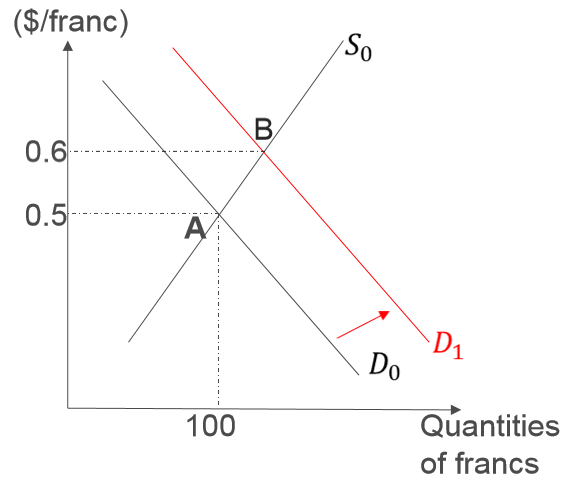

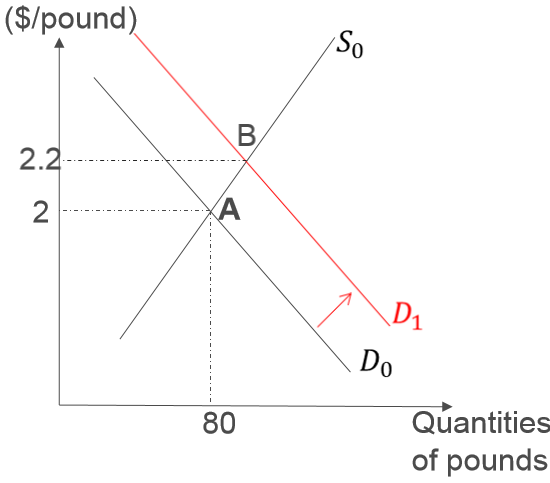

(1) Suppose a permanent increase in U.S. real income.

As a result, Americans purchase more Swiss products, raising the demand for francs from D0 to D1.

Because this increase in demand is the result of long run market forces (recall that chapter 3, market fundamentals such as inflation, GDP determines the long-run movements of exchange rates.), a managed float permits supply and demand conditions to determine the ex-rate.

So, ex-rate will increase to $0.6/franc in the long run.

In this manner, long run movement in exchange rates are determined by the supply and demand for currencies.

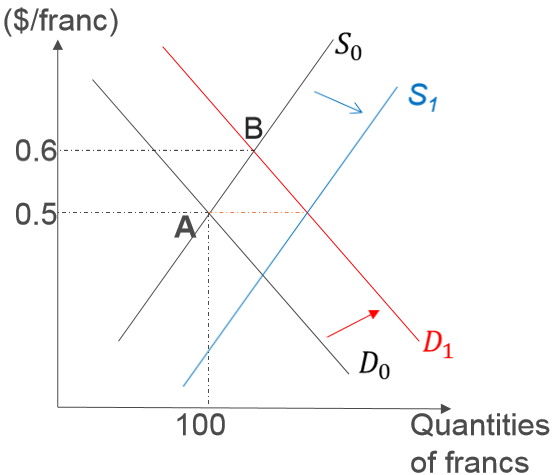

(2) Suppose Swiss securities pay relatively high interest rates.

As a result, Americans purchase more securities, raising the demand for francs from D0 to D1.

Because this increase in demand is the result of short run factors (recall that chapter 3, changes in relative interest rates cause short-term fluctuations of exchange rates), the central bank will respond to this temporary disturbance with exchange intervention.

So, during the time period when demand is at D1, the central bank would intervene by selling francs so as to stabilize the exchange rate at 0.5 in the short run.

Central bank intervention is used to offset temporary fluctuations in exchange rates which would cause uncertainty in carring out transactions in international trade and finance.

3. Exchange Rate Stabilization & Monetary Policy

Central banks can buy and sell foreign currencies to stabilize their values under a system of managed floating ex-rates; another stabilization technique involves a nation’s monetary policy.

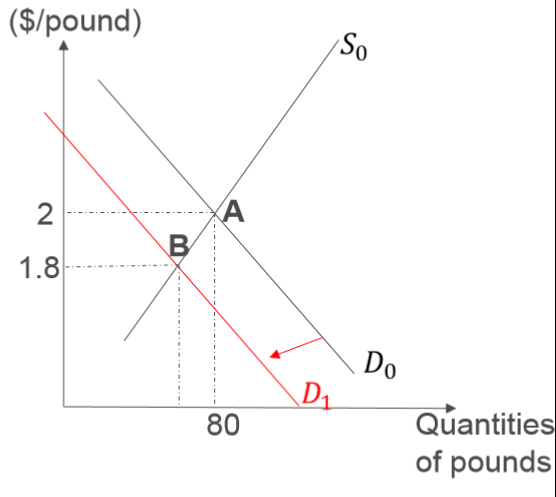

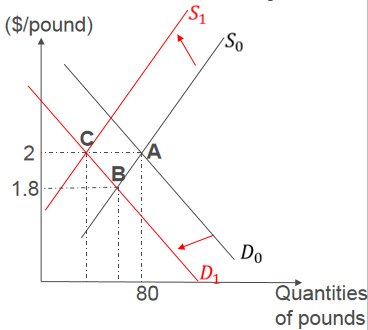

(1) Suppose U.S. imports fewer UK products.

As a result, U.S. demand for pounds decline (D0→D1)

In the absence of central bank intervention, the dollar price of pound falls from $2 to $1.8 so the dollar appreciates against the pound.

To offset the appreciation of dollar, the Fed adopts an expansionary monetary policy to increase the money supply and reduce the relative U.S. interest rates in the short run.

The reduced interest rates will cause the UK demand for U.S. securities to decline, thus decreasing the supply of pound from S0 to S1.

As a result, the exchange rate can be stable at $2/£.

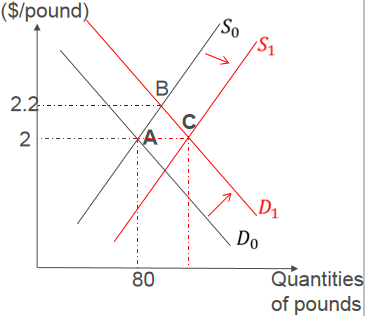

(2) Suppose a temporary increase in UK interest rates causes U.S. investors to demand more pounds to purchase UK securities.

U.S. demand for pounds rise from D0 to D1.

In the absence of central bank intervention, the dollar price of pound rises from $2 to $2.2 so the dollar depreciates against the pound.

To offset the depreciation of dollar, the Fed adopts a contractionary monetary policy to decrease the money supply and raise the relative U.S. interest rates in the short run.

The improved interest rates will cause the UK demand for U.S. securities to rise, thus increasing the supply of pound from S0 to S1.

As a result, the exchange rate can be stable at $2/£.

To conclude, stabilizing a currency's exchange value requires the central bank to adopt an expansionary monetary policy to offset currency appreciation and a contractionary monetary policy to offset currency depreciation.