Chapter 4 Exchange Rate Adjustments and the Balance of Payments

Unit 1

LEARNING OUTCOMES 学习效果:

At the end of this lecture, students should be able to

explain how the ex-rate movements influence the relative production costs and then the relative prices

understand the elasticity approach and Marshall-Lerner condition

examine under what circumstances will currency depreciation reduce a trade deficit

FOCUS AND DIFFICULTIES 知识重难点:

Focus: Effects of Exchange Rate Changes on Costs and Prices, Effects of Currency Depreciation on a nation's trade balance.

Difficulty: Marshall-Lerner condition

LECTURE VIDEO 授课视频:

LEARNING OUTLINE 学习大纲:

1. Effects of Exchange Rate Changes on Costs

Industries that comptete with foreign producers or rely on imported inputs in production can be largely affected by ex-rates fluctuations.

Changing ex-rates influence the international competitiveness of a nation's industries through their influence on relative costs.

A low level of relative costs improves its international competitiveness; while, a high level of relative costs would reduce its international competitiveness.

Example:

A U.S. steel manufacturer uses labor, materials(iron ore铁矿石, coal煤, limestone石灰石) and other inputs to produce steel

Assume a two-country world: U.S. and Switzerland. So in international maket, U.S. steel producers compete with Swiss steel producers.

If their steel products are identical quality, the one who bears lower costs relatively or offers a lower price in terms of one common currency can win a larger share of the steel market and thus enjoy a stronger competitiveness.

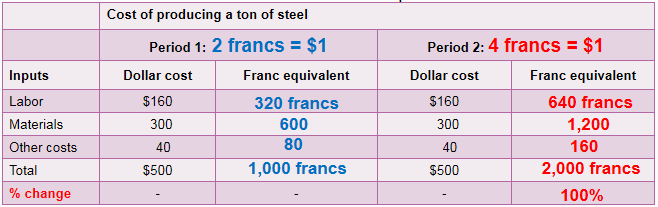

Case 1: No foreign sourcing---All of a firm's inputs are acquired domestically and their costs are denominated in the domestic currency (U.S. dollar in this example).

In period 1, the firm's production cost per ton of steel is $500, equivalent to 1000 francs at the ex-rate 2 franc/dollar.

Suppose that in period 2, the dollar appreciates by 100%, to 4franc/dollar.

With the dollar appreciation, the firm's production costs in dollar terms will not be affected, because all inputs are acquired in U.S. market and priced in dollars; however, in terms of franc, these costs increase from 1000 francs to 2000 francs, by 100%.

Therefore, the 100% dollar appreciation results in a 100% increase in the firm's franc-equivalent production cost.

Thus, the rising production costs would reduce the US firm's international competitiveness, when compete with the Swiss local producer or Swiss exporters whose franc costs remain unchanged.

As a result, an appreciation in the domestic currency’s exchange value increases a firm’s costs by the same proportion, in terms of the foreign currency when all inputs are bought domestically.

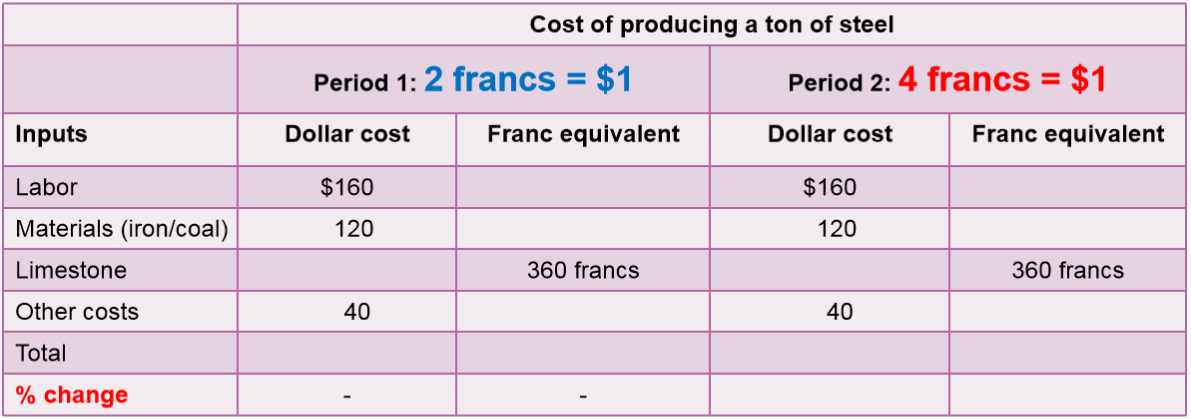

Case 2: Foreign sourcing---manufacturers obtain inputs from abroad whose costs are denominated in terms of a foreign currency ( some costs denominated in $ and some costs in francs in this example)

The U.S. firm purchases limestone石灰石 from Swiss suppliers and these costs are denominated in francs, 360 francs per ton of steel; while, all else inputs are acquired from U.S. local markets, priced in dollars.

In particular, limestone obatined from Swiss market costs the U.S. steel producer 360 francs per ton of steel, in both period 1 and period 2. All else inputs like labor, coal, iron are acquired from U.S. markets and so priced in $, and their dollar prices are unchanged during period 1 and period 2.

In period 1, the firm’s production cost per ton of steel is $500, equivalent to 1000 francs at the ex-rate $0.5/SFr.

Once again, the dollar appreciates from 2franc/$ to 4franc/$, by 100%.

As we can see, due to the 100% dollar appreciation, the franc costs of labor, iron, coal and other inputs increase by 100%; while, becasue limestone was priced in francs, the franc cost of limestone remains unchanged at 360 francs.

In all, total franc cost rises from 1000 francs to 1640 francs, by 64%, less than 100%.

Thus, when some inputs are obtained abroad, the dollar appreciation still reduces the firm’s international competitiveness, but not as much as in the case 1.

These two cases illustrate that: as foreign-currency-denominated costs become a larger portion of a producer's total costs, an appreciation of the domestic currency’s exchange value leads to a smaller increase in the foreign-currency cost of the firm’s output compared to the cost changes that occur when all input costs are denominated in the domestic currency.

These conclusions imply that to eliminate the impact of currency appreciation on their competitiveness, firms can purchase the inputs of production in foreign markets or move the production offshore; since foreign currency denominated inputs become cheaper, it would be helpful to offset higher domestic currency related costs and chill the rising total production costs in foreign currency terms.

2. Effects of Exchange Rate Changes on Costs and Prices

Changes in relative costs because of ex-rate fluctuations also influence relative prices and the volume of goods traded among nations.

Generally, when production costs rise, the firm is likely to raise selling prices so as to achieve its profit goal; conversely, when production costs decline, the firm tend to lower selling prices so as to attract more customers and improve its market share, under the condition of stable profits.

As a dollar appreciation increases U.S. production costs relatively, U.S. firms tend to raise export prices in terms of foreign currency so as to achieve their profits target, thus reducing U.S. exports abroad; meanwhile, thanks to a relatively lower costs, foreign producers would be able to lower their product prices, thus U.S. consumers import more foreign products.

Conversely, a dollar depreciation reduces relative U.S. production costs, tends to lower U.S. relative export prices in terms of foreign currency, thus increasing US exports and decreasing US imports.

However, some factors govern the extent by which ex-rate movements lead to relative price changes among nations. In other words, it is not necessarily for firms to change their relative prices when domestic currency apperciates or depreciates. Price strategy depends on many other factors, besides the ex-rate movements.

For instance, since a dollar appreciation tends to raise the US relative production costs and reduce its international competitiveness, some US exporters may decide to maintain its prices and its market share rather than raise its prices and obtain its target profits.

Moreover, perception about long-term trends in ex-rates also promote price rigidity; for instance, if the US exporters consider a dollar’s appreciation as temporary, they would be less incentive to raise prices.

Besides, the greater the degree of product differentiation, the less the substitutability of their products, the greater control producers can have over prices. For these kind industries, ex-rate fluctuations, to a large extent, would not bother the pricing policies of such producers.

Therefore, the extent by which ex-rate movements lead to relative prices changes among nations would depend on several factors; it is not an absolute thing.

Cost Cutting Strategies of manufacturers in Response to Currency Appreciation

Recall that: Appreciation of home currency raises the relative costs of the nation's firms and thus reduces the international competitiveness of its exporting goods.

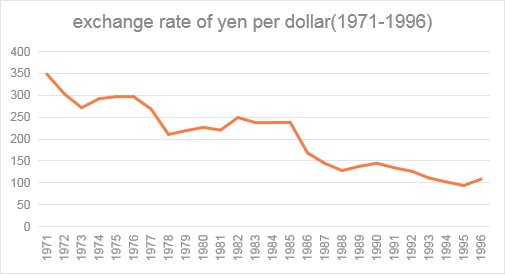

In 1990s, Japan experienced a persistent increase on the value of Japanese yen relative to US dollar.

a. Causes of Yen's appreciation relative to $:

(1)Japan's economic strength was growing relative to that of the United States.

In the early post-war period, Japan implemented the "dodge Line", which eradicated the serious inflation. The economy began to recover, and with a series of financial system reforms, the foundation of economic development was strengthened.

In 1950s to 1970s, Japan's economic growth rate remains above 10% per year on average, with a strong investment demand, a rising productivity growth, growing exports and a lower inflation rate relative to U.S..

In terms of industrial structure, Japan has adapted to changes in domestic and foreign conditions, improved its industrial structure, and constantly established competitive industrial sectors. These factors have made Japan a major producer of home appliances, automobiles and semiconductors in the international market, leading to a large trade surplus.

The oil crisis in 1970s had an important impact on the whole western world. With the increase of production cost, stagflation of different degrees occurred in the United States, Japan and other western countries.

Japan, which relies heavily on energy imports, was particularly hard hit, with double-digit inflation in 1973-75. But the impact of the oil shock was mitigated by rapid adjustments in Japan's industrial policy, which overcame the adverse impact of higher oil prices in a short period of time by improving energy technologies and producing fuel-efficient cars. The Improvement of industrial structure allowed Japan to eliminate the impact of oil shock and recover the economy quickly.

Since 1990, Japan's bubble economy has burst rapidly and its financial assets have been greatly reduced, which has brought a massive blow to Japan's real economy. Japan's initial advantage in economic growth has disappeared.

However, the relative economic strength of the United States and Japan has not changed fundamentally.

(2)Persistent huge surplus on currenct account balance of Japan

In 1980s, Japan experienced Persistent huge surplus on currenct account balance; as a result, Japan's stock of foreign assets increased rapaidly, become the largest creditor in the world, which inevitably pushed up the exchange value of Yen against dollar.

(3)Intervention by western countries and political pressure

The U.S., European union and other trading partners strongly unsatisfied with Japan's huge trade surplus. The western countries believed that the yen exchange rate was too low and decided to intervene by selling dollars in the foreign exchange market jointly.

They signed the Plaza Accord in 1985 to weaken the dollar against the yen in order to reverse the serious trade imbalance between the western countries and Japan.

So, since then, the yen appreciated against dollar by 50% within three years.

Such a persistent appreciation of yen against dollar cause Japanese goods to become less competitive in world markets and makes it harder for Japanese manufacturers to profit out of exports.

b. How did they respond to the impacts of yen’s appreciation on dollar production costs and dollar prices of Japanese export goods?

(1) Japanese manufacturers establish integrated manufacturing bases in the U.S. and in dollar-linked Asia where the dollar depreciates relative to yen..

This strategy allows Japanese firms to use strong yen to purchaser cheaper dollar denominated components and materials from around the world and assemble them where the labor cost was lower, in order to offset the rising costs of domestic inputs.

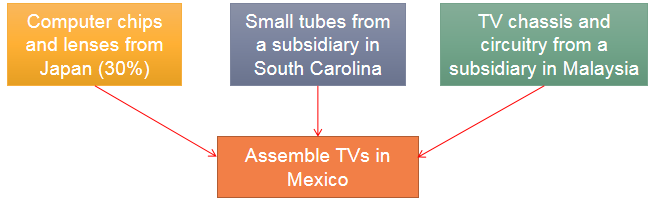

Consider the Japanese electronoic manufacturer Hitachi.

In the mid-1990s, as the yen appreciated against the dollar, Hitachi's global diversification permitted it to sell TVs in the U.S. without raising prices.

In particular, the small tubes came from a subsidiary in South Carolina, denominated in dollars. And, TV chassis and circuitry came from a subsidiary in Malaysia, denominated in dollars. While, only computer chips and lenses came from Japan that amounted to 30% of the value of the parts used in one TV set. In the end, another Hitachi's subsidiary in Mexico assembled the TVs, where the assembling costs such as labor costs were denominated in peso which depreciated against dollar.

Therefore, by sourcing TV production in countries whose curerncies had fallen against the yen, Hitachi was able to remain the dollar price of its TV sets despite the rising yen so as to maintain its market share in US market.

(2) To limit their vulnerability to a rising yen, Japanese manufacturers shifted production from commodity-type goods to high-value products.

Because commodity-type goods (such as metals and textiles) are quite sensitive to price changes so that customers could easily switch to non-Japanese producers who charge lower dollar price for same products.

While, more sophisticated, high-value products—such as transportation equipment and electrical machinery—are less sensitive to price changes so that even if the dollar price of those Japanese products rises, customers are less incentive to switch in short run.

Consider the Japanese auto industry.

To offset the rising yen, Japanese automakers cut the yen prices of their cars and thus experienced falling unit-profit margins.

Meanwhile, they reduced manufacturing costs by improving worker productivity, importing materials and parts whose prices were denominated in depreciating currencies against yen, and outsourcing larger amounts of a vehicle’s production to transplant factories in countries whose currencies depreciated against yen.

For example, Toyota corporation cut costs at full stretch by pressuring Japanese suppliers to lower part prices, adopting standardized methods to produce vehicles, reintroducing foreign made parts inferior but cheaper to domestically produced parts , and setting up manufacturing bases in Southeast Asia and South America.

3. Will Currency Depreciation Reduce a Trade Deficit?

The Elasticity Approach

Currency depreciation could affect a nation’s trade balance through changes in the relative prices of g&s.

A trade deficit nation can reverse its imbalance by lowering its relative prices, so that exports increase and imports decrease.

However, the ultimate outcome of currency depreciation depends on the price elasticity of demand for a nation’s imports and the price elasticity of demand for its exports.

Recall that the price elasticity of demand refers to the responsiveness of buyers to changes in price.

And the elasticity measures the % change in quantity demanded resulting from a 1% change in price.

Ed=; in other words, percentage change in quantity demanded (

)= percentage change in price(

) × Ed.

If the ratio exceeds 1, it is said to be elastic demand; if the ratio is less than 1, demand is said to be inelastic; if the ratio equals to 1, it is considered as unitary elastic demand.

Given the basic properties of growth rate, if Z function is the product term of X function and Y function, the growth rate of Z variable equals the growth rate of X plus the growth rate of Y.

It implies that if V(·)=P(·)*Q(·), then g(V)=g(P)+g(Q), where g(·)refers to growth rate.

Example: the currency depreciating country, U.K..

Suppose that British pounds depreciate by 10% against dollar.

Assume no change in the sellers’ prices in their own currency.

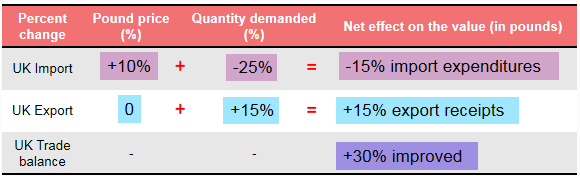

Case 1: Improved trade balance

Assume the UK demand elasticity for imports equals 2.5 and the US demand elasticity for UK exports equals 1.5; the sum of elasticities is 4.

=2.5,

=1.5,

+

=4>1

U.K. import goods from U.S.:

The dollar price of U.S. goods sold is assumed to be constant.

10% depreciation of pound would result in 10% rise in the pound cost of U.K. import.

UK consumers would reduce their purchases from U.S..

Under the UK demand elasticity for imports of 2.5, a 10% rise in pound price of UK imports would lead to a 25% decline in the quantity of UK imports demanded.

=

×

=10%*2.5=25%

V(UK import)=pound price of UK imported goods * the quantity of import demanded.

Thus, with 10% rise in pound price of import and 25% decline in the quantity of import demanded, the value of UK imports will decline by 15% (=10%+(-25%)).

UK export goods to U.S.

The pound price of UK goods sold is assumed to be unchanged.

10% depreciation of pound (namely 10% appreciation of dollar) would result in 10% decline in the dollar costs of U.S. purchases for UK goods.

Therefore, U.S. consumers would increase their purchases from U.K..

Under the US demand elasticity for UK exports of 1.5, a 10% decline in the dollar price of UK exports would lead to a 15% rise in quantity of UK exports demanded.

=

×

=10%*1.5=15%

Thus, with no change in pound price of UK export and 15% rise in the quantity of export demanded, the value of UK exports will rise by 15% (=0%+15%).

UK trade balance= the value of UK export-the value of UK import, thus the UK trade balance is being improved due to a 15% decline in import expenditures along with a 15% rise in export receipts.

To conclude, with the sum of the elasticities exceeding 1, a currency depreciation improves the nation’s trade balance.

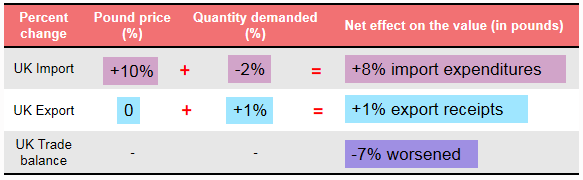

Case 2: Worsened trade balance

Assume the UK demand elasticity for imports equals 0.2 and the US demand elasticity for UK exports equals 0.1; the sum of elasticities is 0.3.

=0.2,

=0.1,

+

=0.3<1

U.K. import goods from U.S.:

The dollar price of U.S. goods sold is assumed to be constant.

Because of 10% pound depreciation, foreign goods cost UK consumers more pounds, 10% more than before.

Thus, UK consumers purchase fewer quantity of foreign goods. So, the quantity of UK imports demanded decrease by 2%, equals 10% time 0.2.

=

×

=10%*0.2=2%

Thereby, 10% rise in pound price of UK import along with 2% decline in quantity of UK import demanded lead to 8% rise in the value of UK imports (=10%+(-2%)).

UK export goods to U.S.

The pound price of UK goods sold is assumed to be unchanged.

Because of 10% pound depreciation (namely 10% dollar appreciation), UK goods cost U.S. consumers fewer dollars, 10% less than before.

Thus, U.S. consumers purchase a larger quantity of UK goods. So, the quantity of UK exports demanded rise by 1%, equals 10% time 0.1.

=

×

=10%*0.1=1%

No change in pound price of UK export together with 1% rise in quantity of UK export demanded lead to 1% rise in the value of UK exports.

Therefore, UK trade balance is being worsened due to a 8% rise in import expenditures along with a 1% rise in export receipts.

To conclude, with the sum of the elasticities less than 1, a currency depreciation worsens the nation’s trade balance.

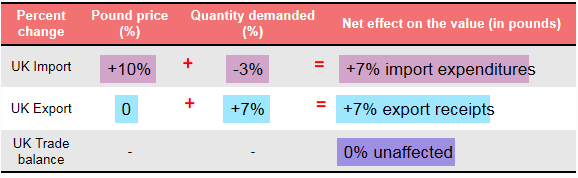

Case 3: Unaffected trade balance

Assume the UK demand elasticity for imports equals 0.3 and the US demand elasticity for UK exports equals 0.7; the sum of elasticities is 1.

=0.3,

=0.7,

+

=1<1

U.K. import goods from U.S.:

The dollar price of U.S. goods sold is assumed to be constant.

10% pound depreciation will result in 10% rise in pound price of UK import, thus the quantity of UK import demanded decreases by 3%.

=

×

=10%*0.3=3%

Combining 10% rise in pound price of UK import and 3% decline in quantity of import demanded, the value of UK import increases by 7%.

UK export goods to U.S.

The pound price of UK goods sold is assumed to be unchanged.

10% pound depreciation will result in 10% decline in dollar price of UK export, thus the quantity of UK export demanded increases by 7%.

=

×

=10%*0.7=7%

Combining no change in pound price of UK export and 7% increase in quantity of export demanded, the value of UK export increases by 7%.

Therefore, UK trade balance is unaffected by a pound depreciation when the sum of elasticities equals 1.

Marshall-Lerner condition

(1) Depreciation will improve the trade balance if the currency-depreciating nation’s demand elasticity for imports plus the foreign demand elasticity for the nation’s exports exceeds one;

(2) Depreciation will worsen the trade balance if the sum of the demand elasticities is less than one;

(3) The trade balance will be neither helped nor hurt if the sum of the demand elasticities equals one.

To work efficiently, the Marshall-Lerner condition depends on some simplifying assumptions. First, a nation’s trade balance is in equilibrium when the depreciation occurs; second, no change in the sellers’ prices in their own currency.

In all, the Marshall-Lerner condition told us that the price effects of currency depreciation on the home-country’s trade balance depends on the demand elasticity for imports and exports.

Specifically, the depreciation work best when demand elasticity is high.