Chapter 2 Foreign Exchange

Unit 4

LEARNING OUTCOMES 学习效果:

At the end of this lecture, students should be able to

understand the concepts of exchange arbitrage and interest arbitrage

determine how to profit from two-point and three-point arbitrage

explain how to cover/uncover international investment

FOCUS AND DIFFICULTIES 知识重难点:

Focus: two-point and three-point arbitrage, covered interest arbitrage

Difficulty: implications from uncovered interest parity and covered interest parity

LECTURE VIDEO 授课视频:

LEARNING OUTLINE 学习大纲:

1. Exchange Arbitrage

or currency arbitrage, refers to simultaneous purchase and sale of a currency in different foreign exchange markets in order to profit from exchange rate differentials in the two locations.

In other words, arbitrage is the practice of taking advantage of a price difference between two or more markets. And the simultaneous purchase and sale of a currency are spot transactions.

Two types of arbitrage:

(1) Two-Point Arbitrage

Two-point arbitrage refers to a situation that there exists a difference of same exchange rate between two locations at same time, then the arbitrager can buy the currency where they are cheap and meanwhile sell them where they are expensive so that he can profit.

For example, pounds were being exchanged at $1.70 per pound in London, and $1.60 per pound at same time in New York.

The pound is expensive in London while cheaper in New York relatively.

Following the profitable rule: buy low sell high, arbitragers will buy pounds in New York and sell pounds in London at the same time.

For each pound sold at $1.7 and bought at $1.6, the arbitrage profit is $0.1.

Many arbitragers would seek this opportunity, increasing the demand for pounds in New York and increasing the supply of pounds in London.

Then the ER($/£) then would increase in New York and decrease in London until they are driven to be essentially same.

In the end, we find that the difference of same exchange rate between two locations will disappear.

In other words, arbitrage ensures rates in different locations are essentially the same.

(2) Three-point Arbitrage

Profiting from misalignments among two exchange rates against a common currency (usually the dollar) and the cross-rate between the other two currencies

For example, assume that arbitragers start with dollars and want to end up with dollars.

Three currencies: the U.S. dollar, Swiss francs, and British pounds, all of which are traded in New York, Geneva, and London. Suppose that the dollar price of pound in New York is 1.6, the cross-rate of franc per pound in Geneva is 4, and the dollar price of franc in London is 0.5.

In New York, $1.50 =£1.00

In Geneva, 4 francs =£1.00

In London, $0.50 =1 franc

a) Is there an opportunity to profit from exchange arbitrage?

When the cross-rate in one market is not equal to the ratio of dollar prices of two other currencies computed from other two markets, there is an arbitrage opportunity to profit. when it is equal, there is no opportunity.

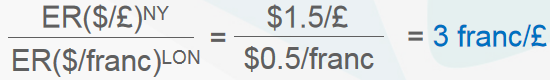

Compute the ratio of the dollar prices of pound and franc:

Since the cross-rate of franc per pound in Geneva (4franc/£) is different from the computed ratio, there is an arbitrage opportunity to profit.

b) How to profit? Which currency to buy or sell? Where to buy or sell that currency?

Since the cross rate of franc per pound in Geneva is higher than the computed ratio derived from other two markets, it indicates that the pound is more expensive relative to franc in Geneva than that in other two markets.

Therefore, there exists the chance that arbitragers sell pounds at 4 franc/£ in Geneva which can help receive more francs than do that in other two markets.

So far, we can confirm that arbitragers must sell pounds for francs in Geneva. Using backward process analysis, selling pounds in Geneva requires arbitragers who start with dollars in hands to acquire pounds firstly.

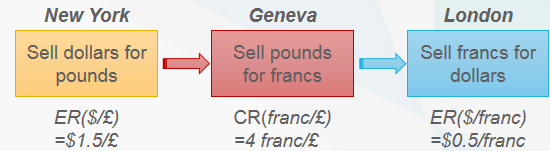

Thus, arbitragers would sell dollars for pounds in New York at $1.5/£; then, they go to Geneva market to sell those pounds for francs at 4 franc/£; after receiving francs in Geneva, they finally go to London market to sell francs for dollars.

Assume that arbitragers start with 1.5 million dollars. Firstly, arbitagers sell $1.5 million for £1 million in New York; secondly, they sell those 1 million pounds for 4 million francs in Geneva; finally,they sell out 4 million francs for 2 million dollars in London. Thus, starting with 1.5 million dollars and ending up with 2 million dollars, arbitragers gain a risk-free profit of 0.5 million dollars.

c) Subsequent performance:

As a large amount of this triangular arbitrage occurs, it will changes the demand and supply for francs and pounds in FX market.

In New York, the increasing demand for pounds will cause the dollar price of pound to rise.

In Geneva, the extra supply of pounds will cause the franc-pound cross rate to decline.

In London, the extra supply of francs will cause the dollar price of franc to decline.

Due to the demand and supply pressures, the exchange rates will change until the cross rate of francs per pound essentially equals the ratio of the dollar-pound exchange rate to the dollar-franc exchange rate.

In the end, the opportunity for profits from triangular arbitrage will disappear.

Therefore, these transactions tend to cause shifts in all three ex-rates that bring them into proper alignment and eliminate the profitability of arbitrage.

In conclusion, exchange arbitrage results in an identical price for the same currency in different locations, and ensures that currency ex-rates are mutually consistent throughout the world.

2. Interest Arbitrage, Currency Risk, and Hedging

When making decisions about international investments, investors compare the returns of foreign investment with that of domestic investment. If the expected return on foreign investments was higher, investors would shift their funds abroad.

We consider interest arbitrage as the process of moving funds into foreign currencies to take advantage of higher investment yields abroad.

While, foreign currency denominated investments were exposed to ex-rate risk because of the unpredictable future spot rate.

If investors do nothing with the risk, it is known as the uncovered interest arbitrage. While, if investors hedge against this risk, it is known as the covered interest arbitrage.

(1) Uncovered Interest Arbitrage

a) Consider U.S. investors start with 1 dollar today. U.S. investors could simply invest one dollar today in U.S. and in 3-month time they can receive (1+) future dollars.

b) Or they could move their money to Britain. Using one dollar, they can buy 1/e pounds in the spot market. Then, they invest these pounds in Britain and at maturity they will receive (1+)/e pounds. Since they have an expectation towards future spot rate (

), they expect to convert the pound-income back into (1+

)*

/e future dollars.

In other words, for each dollar uncovered invested in Britain today, investors expect to receive (1+)*

/e future dollars.

Compared to the U.S., the extra return from investing in Britain equals the expected uncovered interest differential ("EUD") as follows: EUD=(1+)*

/e -(1+

).

Positive EUD indicates that investments in Britain would be more profitable and negative EUD tells that domestic investment would be better.

Given the EUD approximation as follows: EUD=(-

)+expected appreciation of pound.

The uncovered interest parity refers to a condition that EUD is zero, also known as international Fisher effect.

If the uncovered interest parity holds, thus EUD=0;

If <

, £ is expected to appreciate; If

>

, £ is expected to depreciate.

Therefore, a country's currency is expected to appreciate (depreciate) by as much as its interest rates is lower (higher) than the interest rate in the other country, if the uncovered interest parity exists.

(2) Covered Interest Arbitrage

If investors shift their funds to foreign currency denominated financial assets for its higher yield, returns in terms of foreign currency will be received in future and investors are exposed to ex-rate risk during this period.

To hedge against this risk, investors would contract to sell the forward foreign currency into dollars at a prearranged price. Such this investment is known as the covered interest arbitrage.

a) Start with one dollar, US investors could simply invest one dollar at interest in U.S., getting (1+) future dollars.

b) Or U.S. investors could route the money through Britain, with one dollar, buying pounds in the spot market, obtaining 1/e pounds. Then, they invest 1/e pounds in Britain and expect to get (1+)/e pounds at maturity. Meanwhile, they sell (1+

)/e pounds in forward market at the forward rate (f) to receive dollars in the future. At maturity date, they receive (1+

)/e pounds and sell them into the forward contract to receive an ensured amount of (1+

)*f/e future dollars.

Notice that the forward contract is signed today, with identical amount of pounds that will be received from the British investment, and with a delivery date same to the maturity of the investment.

Which route investors should choose will depend on the difference between these two returns, called the covered interest differential (CD): CD=(1+)*f/e-(1+

).

If CD is positive, investors should invest in Britain. If CD is negative, inesvtors would better invest at home.

Applying the forward premium into the CD expression, we obtain the approximation: CD=(-

)+Forward premium.

Covered Interest Parity refers to the condition that CD=(-

)+F=0

If <

, F>0, forward premium on pounds

If >

, F<0, forward discount on pounds

The covered interest parity indicates that a country with a lower interest rate than the US interest rate tends to have a forward premium on its currency, whereas a country with a higher interest rate relative to the US interest rate will have a forward discount on its currency.

3. Speculation

Speculation refers to the attempt to profit by trading on expectations about prices in the future.

Namely, speculators buy currencies that they expect to go up in value and sell currencies that they expect to go down in value.

Currency speculation could be either a stabilizing speculation or a destabilizing speculation.

(1) Stabilizing speculation works against market forces by moderating or reversing a rise/fall in a currency's exchange rate.

For example, if pounds depreciate relative to dollars, speculators would purchase £ with $, increasing demand for £ so that moderates its depreciation.

Stabilizing speculation performs a useful function for bankers and businessman who desire stable ex-rates.

(2) Destabilizing speculation works along with market forces by amplifying and reinforcing fluctuations in a currency’s exchange rate.

For instance, if £ was expected to depreciate, speculators would sell £ with huge amounts and then £ will depreciate further in future.

The great fluctuations in ex-rates caused by destabilizing speculation lead to high cost of hedging for exporters and importers investors, which discourage international trade and disrupt international investment activity.

Because destabilizing speculation can disrupt international transactions in several ways, government officials propose the regulations of FX markets to reduce the amount of destabilizing speculation.