-

1 PrerequisitesPrer...

-

2 Free energy

-

3 Enzymes &...

-

4 Active site,...

-

5 Amino Acid

-

6 Peptide

-

7 Protein

-

8 Hydrolysis

Prerequisites(预备知识)

Free energy

Article Link: https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/energy-and-enzymes/free-energy-tutorial/a/gibbs-free-energy

Introduction

When you hear the term “free energy,” what do you think of? Well, if you’re goofy like me, maybe a gas station giving away gas. Or, better yet, solar panels being used to power a household for free. There’s even a rock band from Philadelphia called Free Energy (confirming my longtime suspicion that many biology terms would make excellent names for rock bands).

These are not, however, the meanings of “free energy” that we’ll be discussing in this article. Instead, we’re going to look at the type of free energy that is associated with a particular chemical reaction, and which can provide a measure of how much usable energy is released (or consumed) when that reaction takes place.

Free energy

A process will only happen spontaneously, without added energy, if it increases the entropy of the universe as a whole (or, in the limit of a reversible process, leaves it unchanged) – this is the Second Law of Thermodynamics. But to me at least, that's kind of an abstract idea. How can we make this idea more concrete and use it to figure out if a chemical reaction will take place?

Basically, we need some kind of metric that captures the effect of a reaction on the entropy of the universe, including both the reaction system and its surroundings. Conveniently, both of these factors are rolled into one convenient value called the Gibbs free energy.

The Gibbs free energy (G) of a system is a measure of the amount of usable energy (energy that can do work) in that system. The change in Gibbs free energy during a reaction provides useful information about the reaction's energetics and spontaneity (whether it can happen without added energy). We can write out a simple definition of the change in Gibbs free energy as:

In other words, ΔG is the change in free energy of a system as it goes from some initial state, such as all reactants, to some other, final state, such as all products. This value tells us the maximum usable energy released (or absorbed) in going from the initial to the final state. In addition, its sign (positive or negative) tells us whether a reaction will occur spontaneously, that is, without added energy.

When we work with Gibbs free energy, we have to make some assumptions, such as constant temperature and pressure; however, these conditions hold roughly true for cells and other living systems.

Gibbs free energy, enthalpy, and entropy

In a practical and frequently used form of Gibbs free energy change equation, ΔGis calculated from a set values that can be measured by scientists: the enthalpy and entropy changes of a reaction, together with the temperature at which the reaction takes place.

Let’s take a step back and look at each component of this equation.

∆H is the enthalpy change. Enthalpy in biology refers to energy stored in bonds, and the change in enthalpy is the difference in bond energies between the products and the reactants. A negative ∆H means heat is released in going from reactants to products, while a positive ∆H means heat is absorbed. (This interpretation of ∆H assumes constant pressure, which is a reasonable assumption inside a living cell).

∆S is the entropy change of the system during the reaction. If ∆S is positive, the system becomes more disordered during the reaction (for instance, when one large molecule splits into several smaller ones). If ∆S is negative, it means the system becomes more ordered.

Temperature (T) determines the relative impacts of the ∆S and ∆H terms on the overall free energy change of the reaction. (The higher the temperature, the greater the impact of the ∆S term relative to the ∆H term.) Note that temperature needs to be in Kelvin (K) here for the equation to work properly.

Reactions with a negative ∆G release energy, which means that they can proceed without an energy input (are spontaneous). In contrast, reactions with a positive ∆G need an input of energy in order to take place (are non-spontaneous). As you can see from the equation above, both the enthalpy change and the entropy change contribute to the overall sign and value of ∆G. When a reaction releases heat (negative ∆H) or increases the entropy of the system, these factors make ∆Gmore negative. On the other hand, when a reaction absorbs heat or decreases the entropy of the system, these factors make ∆G more positive.

By looking at ∆H and ∆S, we can tell whether a reaction will be spontaneous, non-spontaneous, or spontaneous only at certain temperatures. If a reaction both releases heat and increases entropy, it will always be spontaneous (have a negative ∆G), regardless of temperature. Similarly, a reaction that both absorbs heat and decreases entropy will be non-spontaneous (positive ∆G) at all temperatures. Some reactions, however, have a mix of favorable and unfavorable properties (releasing heat but decreasing entropy, or absorbing heat but increasing entropy). The ∆G and spontaneity of these reactions will depend on temperature, as summarized in the table at right.

[Why can these terms predict spontaneity?]

Endergonic and exergonic reactions

Reactions that have a negative ∆G release free energy and are called exergonic reactions. (Handy mnemonic: EXergonic means energy is EXiting the system.) A negative ∆G means that the reactants, or initial state, have more free energy than the products, or final state. Exergonic reactions are also called spontaneous reactions, because they can occur without the addition of energy.

Reactions with a positive ∆G (∆G > 0), on the other hand, require an input of energy and are called endergonic reactions. In this case, the products, or final state, have more free energy than the reactants, or initial state. Endergonic reactions are non-spontaneous, meaning that energy must be added before they can proceed. You can think of endergonic reactions as storing some of the added energy in the higher-energy products they form1start superscript, 1, end superscript.

It’s important to realize that the word spontaneous has a very specific meaning here: it means a reaction will take place without added energy, but it doesn't say anything about how quickly the reaction will happen2start superscript, 2, end superscript. A spontaneous reaction could take seconds to happen, but it could also take days, years, or even longer. The rate of a reaction depends on the path it takes between starting and final states (the purple lines on the diagrams below), while spontaneity is only dependent on the starting and final states themselves. We'll explore reaction rates further when we look at activation energy.

Spontaneity of forward and reverse reactions

If a reaction is endergonic in one direction (e.g., converting products to reactants), then it must be exergonic in the other, and vice versa. As an example, let’s consider the synthesis and breakdown of the small molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATPA, T, P), which is the "energy currency" of the cell3start superscript, 3, end superscript.

ATPA, T, P is made from adenosine diphosphate (ADPA, D, P) and phosphate (PiP, start subscript, i, end subscript) according to the following equation:

ADPA, D, P + PiP, start subscript, i, end subscript →right arrow ATPA, T, P + H2OH, start subscript, 2, end subscript, O

This is an endergonic reaction, with ∆G = +7.3plus, 7, point, 3 kcal/molk, c, a, l, slash, m, o, l under standard conditions (meaning 11 MM concentrations of all reactants and products, 11 atma, t, mpressure, 2525 degrees CC, and pHp, H of 7.07, point, 0). In the cells of your body, the energy needed to make ATPA, T, P is provided by the breakdown of fuel molecules, such as glucose, or by other reactions that are energy-releasing (exergonic).

The reverse process, the hydrolysis (water-mediated breakdown) of ATPA, T, P, is identical but with the reaction flipped backwards:

ATPA, T, P + H2OH, start subscript, 2, end subscript, O →right arrow ADPA, D, P + PiP, start subscript, i, end subscript

This is an exergonic reaction, and its ∆G is identical in magnitude and opposite in sign to that of the ATP synthesis reaction (∆G = −7.3minus, 7, point, 3 kcal/molk, c, a, l, slash, m, o, l under standard conditions). This relationship of same magnitude and opposite signs will always apply to the forward and backward reactions of a reversible process.

Non-standard conditions and chemical equilibrium

You may have noticed that in the above section, I was careful to mention that the ∆G values were calculated for a particular set of conditions known as standard conditions. The standard free energy change (∆Gº’) of a chemical reaction is the amount of energy released in the conversion of reactants to products under standard conditions. For biochemical reactions, standard conditions are generally defined as 2525

The conditions inside a cell or organism can be very different from these standard conditions, so ∆G values for biological reactions in vivo may vary widely from their standard free energy change (∆Gº’) values. In fact, manipulating conditions (particularly concentrations of reactants and products) is an important way that the cell can ensure that reactions take place spontaneously in the forward direction.

Chemical equilibrium

To understand why this is the case, it’s useful to bring up the concept of chemical equilibrium. As a refresher on chemical equilibrium, let’s imagine that we start a reversible reaction with pure reactants (no product present at all). At first, the forward reaction will proceed rapidly, as there are lots of reactants that can be converted into products. The reverse reaction, in contrast, will not take place at all, as there are no products to turn back into reactants. As product accumulates, however, the reverse reaction will begin to happen more and more often.

This process will continue until the reaction system reaches a balance point, called chemical equilibrium, at which the forward and reverse reactions take place at the same rate. At this point, both reactions continue to occur, but the overall concentrations of products and reactants no longer change. Each reaction has its own unique, characteristic ratio of products to reactants at equilibrium.

When a reaction system is at equilibrium, it is in its lowest-energy state possible (has the least possible free energy). If a reaction is not at equilibrium, it will move spontaneously towards equilibrium, because this allows it to reach a lower-energy, more stable state. This may mean a net movement in the forward direction, converting reactants to products, or in the reverse direction, turning products back into reactants.

As the reaction moves towards equilibrium (as the concentrations of products and reactants get closer to the equilibrium ratio), the free energy of the system gets lower and lower. A reaction that is at equilibrium can no longer do any work, because the free energy of the system is as low as possible4start superscript, 4, end superscript. Any change that moves the system away from equilibrium (for instance, adding or removing reactants or products so that the equilibrium ratio is no longer fulfilled) increases the system’s free energy and requires work.

How cells stay out of equilibrium

If a cell were an isolated system, its chemical reactions would reach equilibrium, which would not be a good thing. If a cell's reaction reached equilibrium, the cell would die because there would be no free energy left to perform the work needed to keep it alive.

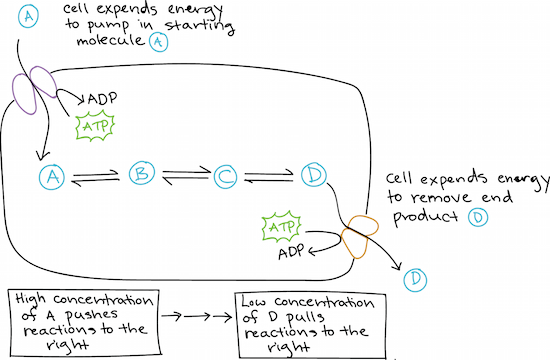

Cells stay out of equilibrium by manipulating concentrations of reactants and products to keep their metabolic reactions running in the right direction. For instance:

They may use energy to import reactant molecules (keeping them at a high concentration).

They may use energy to export product molecules (keeping them at a low concentration).

They may organize chemical reactions into metabolic pathways, in which one reaction "feeds" the next.

Providing a high concentration of a reactant can "push" a chemical reaction in the direction of products (that is, make it run in the forward direction to reach equilibrium). The same is true of rapidly removing a product, but with the low product concentration "pulling" the reaction forward. In a metabolic pathway, reactions can "push" and "pull" each other because they are linked by shared intermediates: the product of one step is the reactant for the next5,6start superscript, 5, comma, 6, end superscript.

Curious how this pushing and pulling actually works? Check out the reaction coupling video to learn more!

Article Link:http://www.worthington-biochem.com/introbiochem/substrateconc.html

More details on Km Value, check: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michaelis%E2%80%93Menten_kinetics

or https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E7%B1%B3%E6%B0%8F%E5%B8%B8%E6%95%B0

More details on Enzyme,

check: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enzyme

or https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%85%B6/107742?fr=aladdin

Introduction to Enzymes

The following has been excerpted from a very popular Worthington publication which was originally published in 1972 as the Manual of Clinical Enzyme Measurements. While some of the presentation may seem somewhat dated, the basic concepts are still helpful for researchers who must use enzymes but who have little background in enzymology.

Substrate Concentration

It has been shown experimentally that if the amount of the enzyme is kept constant and the substrate concentration is then gradually increased, the reaction velocity will increase until it reaches a maximum. After this point, increases in substrate concentration will not increase the velocity (delta A/delta T). This is represented graphically in Figure 8.

It is theorized that when this maximum velocity had been reached, all of the available enzyme has been converted to ES, the enzyme substrate complex. This point on the graph is designated Vmax. Using this maximum velocity and equation (7), Michaelis developed a set of mathematical expressions to calculate enzyme activity in terms of reaction speed from measurable laboratory data.

The Michaelis constant Km is defined as the substrate concentration at 1/2 the maximum velocity. This is shown in Figure 8. Using this constant and the fact that Km can also be defined as:

Km=K-1 + K2 / K+1

K+1, K-1 and K+2 being the rate constants from equation (7). Michaelis developed the following

Michaelis constants have been determined for many of the commonly used enzymes. The size of Km tells us several things about a particular enzyme.

A small Km indicates that the enzyme requires only a small amount of substrate to become saturated. Hence, the maximum velocity is reached at relatively low substrate concentrations.

A large Km indicates the need for high substrate concentrations to achieve maximum reaction velocity.

The substrate with the lowest Km upon which the enzyme acts as a catalyst is frequently assumed to be enzyme's natural substrate, though this is not true for all enzymes.

Active site

Article Link:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Active_site

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

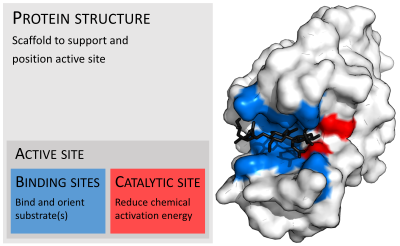

Organisation of enzyme structure and lysozyme example. Binding sites in blue, catalytic site in red and peptidoglycansubstrate in black. (PDB: 9LYZ)

In biology, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate (binding site) and residues that catalyse a reaction of that substrate (catalytic site). Although the active site is small relative to the whole volume of the enzyme(it only occupies 10~20% of the total volume),[1] It is the most important part of the enzyme as it directly catalyzes the chemical reaction. It usually consists of three to four amino acids, while other amino acids within the protein are required to maintain the protein tertiary structure of the enzyme.[2]

Each active site is specially designed in response to their substrates, as a result, most enzymes have specificity and can only react with particular substrates. This specificity is determined by the arrangement of amino acids within the active site and the structure of the substrates. Sometimes enzymes also need to bind with some cofactors to fulfil their jobs. The active site is usually a groove or pocket of the enzyme which can be located in a deep tunnel within the enzyme,[3] or between the interfaces of multimeric enzymes. An active site can catalyse a reaction repeatedly as residues are not altered at the end of the reaction (they may change during the reaction, but are regenerated by the end).[4] This process is achieved by lowering the activation energy of the reaction, so more substrates have enough energy to undergo reaction.

Binding site[edit]

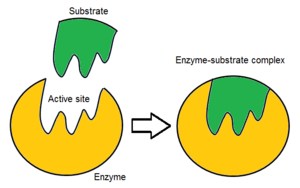

Diagram of the lock and key hypothesis

Diagram of the induced fit hypothesis

Main article: Binding site

Usually, an enzyme molecule has only two active sites, and the active sites fit with one specific type of substrate. An active site contains a binding site that binds the substrate and orients it for catalysis. The orientation of the substrate and the close proximity between it and the active site is so important that in some cases the enzyme can still function properly even though all other parts are mutated and lose function.[5]

Initially, the reaction between the active site and the substrate is non-covalent and temporal. There are four important kinds of interaction that hold the substrate in a right orientation and form an enzyme-substrate complex(ES complex): hydrogen bond, Van der Waals force, hydrophobic interaction and electrostatic force.[6] The charges distribution on the substrate and active site must be complementary, which means all positive and negative charges must be cancelled out. Otherwise, there will be a repulsive force to push them apart. The active site usually contains non-polar amino acids, although sometimes polar amino acids may also occur.[2] The binding of substrate to the binding site requires at least three contact points. For example, when alcohol dehydrogenase catalyses the transfer of H group from alcoholto NADH there are interactions through methyl group, hydroxyl group and pro-R hydrogen group.[7]

In order to function, the proper protein folding and maintaining of the enzyme's tertiary structure rely on various chemical bonds between its amino acids. And external changes can break them down and cause the enzyme to misfold and lose function. For example, denaturation of the protein by high temperatures or extreme pH values will destroy its catalytic activity.This is because Hydrogen bond, which plays an important role in protein folding, is relatively weak and easily affected by external factors.[8]

A tighter fit between an active site and the substrate molecule is believed to increase the efficiency of a reaction.If you increase the tightness between the active site of DNA polymerase and its substrate, the fidelity, which means the correct rate of DNA replication is increased.[9] Most enzymes have deeply buried active sites, which can be accessed by a substrate via access channels.[3]

There are two proposed models of how enzymes fit their specific substrate: the lock and key model and the induced fit model.

Catalytic site[edit]

Main article: Enzyme catalysis

See also: Catalytic triad

The enzyme TEV protease contains a catalytic triad of residues (red) in its catalytic site. The substrate (black) is bound by the binding site to orient it next to the triad. PDB: 1lvm

Once the substrate is bound and oriented to the active site, catalysis can begin. The residues of the catalytic site are typically very close to the binding site, and some residues can have dual-roles in both binding and catalysis.

Catalytic residues of the site interact with the substrate to lower the activation energy of a reaction and so make it proceed faster. They do this by a number of different mechanisms including the approximation of the reactants, nucleophilic/electrophilic catalysis and acid/base catalysis. These mechanisms will be explained below.

Amino acidsArticle Link: http://www.vitamins-supplements.org/amino-acids/ More Details: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amino_acidhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amino_acid | |

| An amino acid is any molecule that contains both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Amino acid is any one of a class of simple organic compounds containing carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and in certain cases sulfur. These compounds are the building blocks of proteins. Amino acids are biochemical building blocks. They form short polymer chains called peptides or polypeptides which in turn form Hundreds of different amino acids exist in nature, and about two dozen of them are important to human nutrition. Essential amino acids are amino acids that cannot be synthesized in the body in adequate amounts and must be obtained from the diet. The essential amino acids are isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine. Non-essential amino acids are those that the body can manufacture from an available source of nitrogen and a carbon skeleton. The nonessential amino acids are arginine, alanine, asparagine, aspartic acid, cysteine, glutamine, glutamic acid, glycine, proline, serine, and tyrosine. Semi-essential amino acids are ones that can sometimes be made internally if conditions are right. Histidine is considered semi-essential because the body does not always require dietary sources of it. Other amino acids, such as carnitine, are used by the body in ways other than protein-building and are often used therapeutically. | |

Proteins | |

Proteins are any of a group of complex organic compounds containing carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and sulfur. Proteins are an essential substance in the diets of humans and most animals because of their constituent amino acids. A protein molecule is a long chain of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Many different proteins are found in the cells of living organisms, but they are all made up of the same 20 amino acids, joined together in varying combinations. Different amino acids are commonly found in proteins, each protein having a unique, genetically defined amino-acid sequence, which determines its specific shape and function. They serve as enzymes, structural elements, hormones, immunoglobulins, etc. and are involved in oxygen transport, muscle contraction, electron transport, and other activities. Proteins are involved in controlling the metabolism of cells, controlling the structure and movement of cells and larger structures and coordinating the response of cells to internal and external factors. Nutritionally, complete proteins are those which contain the right concentrations of the amino acids that humans cannot synthesize from other amino acids or nitrogenous sources. | |

Common amino acids | |

| Alanine - Alanine is one of the simplest of the amino acids and is involved in the energy-producing breakdown of glucose. L-alanine is created in muscle cells from glutamate in a process called transamination. Alanine comes from the breakdown of DNA or the dipeptides, anserine and carnosine, and the conversion of pyruvate, a compound in carbohydrate metabolism. Alanine is used by the body to build Arginine - Arginine is a complex amino acid that is often found at the active (or catalytic) site in proteins and enzymes due to its amine-containing side chain. Arginine is involved in multiple areas of human physiology and metabolism. Arginine plays an important role in cell division, the healing of wounds, removing ammonia from the body, immune function, and the release of hormones. Arginine has a number of functions in the body such as assisting in wound healing, hormone production, immune function and removal of excess ammonia. Asparagine - Asparagine is the ß-amide of aspartic acid synthesized from aspartic acid and ATP (adenosine triphosphate). Asparagine is one of the principal and frequently the most abundant amino acids involved in the transport of nitrogen. Asparagine is very active in converting one amino acid into another (amination and transamination) when the need arises. Asparagine serves as an amino donor in liver transamination processes. Aspartic acid - Aspartic acid is alanine with one of the β hydrogens replaced by a carboxylic acid group. Aspartic acid is a part of organic molecules containing an amino group, which can combine in linear arrays to form proteins in living organisms. Although aspartic acid is considered a non-essential amino acid, it plays a paramount role in metabolism during construction of other amino acids and biochemicals in the citric acid cycle. Among the biochemicals that are synthesized from aspartic acid are asparagine, arginine, lysine, methionine, threonine, isoleucine, and several nucleotides. Carnitine - Carnitine is a non-essential amino acid produced in the liver, brain and the kidneys from the essential amino acids methionine Carnosine - Carnosine is a dipeptide composed of the covalently bonded amino acids alanine and histidine and is found in the brain, heart, skin, muscles, kidneys and stomach. Carnosine is one of the most important and potent natural antioxidant agents which act as universal antioxidants both in the lipid phase of cellular and biological membranes and in the aqueous environment protecting lipids and water-soluble molecules like proteins (including enzymes), DNA and other essential macromolecules from oxidative damage mediated by reactive oxygen species and lipid peroxides. Creatine - Creatine is a natural derivate of an amino acid and is synthesized in the liver, kidneys and pancreas out of arginine, methionine and glycine. Creatine functions to increase the availability of cellular ATP, adenosine triphosphate. Creatine works by acting on mechanisms of ATP by donating a phosphate ion to increase the availability of ATP. Creatine is stored in muscle cells as phosphocreatine and is used to help generate cellular energy for muscle contractions. Citrulline - Citrulline is a precursor to arginine and is involved in the formation of urea in the liver. Arginine is a contributing member of the various amino acids found in the urea cycle, which is responsible for detoxifying ammonia. Citrulline supports the body in optimizing blood flow through its conversion to l-arginine and then nitric oxide (NO). Cysteine - Cysteine is a naturally occurring hydrophobic amino acid which has a sulfhydryl group and is found in most proteins. Cysteine is one of the key components in all living things. N-acetyl cysteine (which contains cysteine) is the most frequently used form of cysteine. N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) helps break down mucus and detoxify harmful substances in the body. Both cysteine and NAC have been shown to increase levels of the antioxidant glutathione. Cystine - Cystine is the product of an oxidation between the thiol side chains of two cysteine amino acids. As such, cystine is not considered one of the 20 amino acids. This oxidation product is found in abundance in a variety of proteins such as hair keratin, insulin, the digestive enzymes chromotrypsinogen A, papain, and trypsinogen where it is heavily involved in stabilizing the tertiary structure of these macromolecules. Glutamine - Glutamine is one of the twenty amino acids generally present in animal proteins. Glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in the body. Over 61% of skeletal muscle tissue is glutamine. It contains two ammonia groups, one from its precursor, glutamate, and the other from free ammonia in the bloodstream. Glutamine is involved in more metabolic processes than any other amino acid. Glutamine is converted to glucose when more glucose is required by the body as an energy source. Glutamine assists in maintaining the proper acid/alkaline balance in the body, and is the basis of the building blocks for the synthesis of RNA and DNA. Glutathione - Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide composed of three different amino acids: glutamate, cysteine and glycine that has numerous important functions within cells. Glutathione plays a role in such diverse biological processes as protein synthesis, enzyme catalysis, transmembrane transport, receptor action, intermediary metabolism, and cell maturation. Glutathione acts as an antioxidant used to prevent oxidative stress in most cells and help to trap free radicals that can damage DNA and RNA. Glycine - Glycine is the simplest amino acid and is the only amino acid that is not optically active (it has no stereoisomers). The body uses it to help the liver in detoxification of compounds and for helping the synthesis of bile acids. It has a sweet taste and is used for that purpose. Glycine is essential for the synthesis of nucleic acids, bile acids, proteins, peptides, purines, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), porphyrins, hemoglobin, glutathione, creatine, bile salts, one-carbon fragments, glucose, glycogen, and l-serine and other amino acids. Histidine - Histidine is one of the basic (with reference to pH) amino acids due to its aromatic nitrogen-heterocyclic imidazole side chain. Histidine is the direct precursor of histamine, it is also an important source of carbon atoms in the synthesis of purines. Histidine is needed to help grow and repair body tissues, and to maintain the myelin sheaths that protect nerve cells. It also helps manufacture red and white blood cells, and helps to protect the body from heavy metal toxicity. Histamine stimulates the secretion of the digestive enzyme gastrin. Hydroxyproline - Hydroxyproline is derived from the amino acid proline and is used almost exclusively in structural proteins including collagen, connective tissue in mammals, and in plant cell walls. An unusual feature of this amino acid is that it is not incorporated into collagen during biosynthesis at the ribosome, but is formed from proline by a posttranslational modification by an enzymatic hydroxylation reaction. Non-hydroxylated collagen is commonly termed pro-collagen. Isoleucine - Isoleucine belongs to a special group of amino acids called branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), which are needed to help maintain and repair muscle tissue. Leucine and valine are other two branched-chain amino acids. Isoleucine is an essential amino acid that is not synthesized by mammalian tissues. Isoleucine is needed for hemoglobin formation and also helps to maintain regular energy levels. Isoleucine is important for stabilizing and regulating blood sugar and energy levels and is required through the diet as it cannot be produced by our bodies. Leucine - Leucine is a member of the branched-chain amino acid family, along with valine and isoleucine. The branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) are found in proteins of all life forms. Leucine ties glycine for the position of second most common amino acid found in proteins with a concentration of 7.5 percent on a molar basis compared to the other amino acids. Leucine is necessary for the optimal growth of infants and for the nitrogen balance in adults. Lysine - Lysine is an essential amino acid that has a net positive charge at physiological pH values making it one of the three basic (with respect to charge) amino acids. Lysine is an essential amino acid because it cannot be synthesized in the body and its breakdown is irreversible. It is an essential building block for all protein, and is needed for proper growth and bone development in children. Lysine helps the body absorb and conserve calcium and it plays an important role in the formation of collagen. Methionine - Methionine is an important amino acid that helps to initiate translation of messenger RNA by being the first amino acid incorporated into the N-terminal position of all proteins. Methionine supplies sulfur and other compounds required by the body for normal metabolism and growth. Methionine reacts with adenosine triphosphate to form S-adenosyl methionine. S-adenosyl methionine is the principal methyl donor in the body and contributes to the synthesis of many important substances, including epinephrine and choline. Phenylalanine - Phenylalanine is an essential amino acid that is also one of the aromatic amino acids that exhibit ultraviolet radiation absorption properties with a large extinction coefficient. Phenylalanine is part of the composition of aspartame, a common sweetener found in prepared foods (particularly soft drinks, and gum). Phenylalanine plays a key role in the biosynthesis of other amino acids and some neurotransmitters. Proline - Proline is a non-essential amino acid that is involved in the production of collagen and in wound healing. Proline is the precursor for hydroxyproline, which the body incorporates into collagen, tendons, ligaments, and the heart muscle. Proline plays important roles in molecular recognition, particularly in intracellular signalling. Proline is an important component in certain medical wound dressings that use collagen fragments to stimulate wound healing. Serine - The methyl side chain of serine contains a hydroxy group making this one of two amino acids that are also alcohols. Serine plays a major role in a variety of biosynthetic pathways including those involving pyrimidines, purines, creatine, and porphyrins. Serine has sugar-producing qualities, and is very reactive in the body. It is highly concentrated in all cell membranes, aiding in the production of immunoglobulins and antibodies. Taurine - Taurine is a non-essential sulfur-containing amino acid that functions with glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid as a neuroinhibitory transmitter. Taurine is the body's water soluble anti-oxidant, and inhibitory neurotransmitter. The major antioxidant activity of taurine derives from its ability to scavenge the reactive oxygen species hypochlorite. Taurine plays an important role in numerous physiological functions. Theanine - L-theanine is the predominant amino acid in green tea and makes up 50% of the total free amino acids in the plant. Theanine is considered to be the main component responsible for the taste of green tea. L-theanine is involved in the formation of the inhibitory neurotransmitter, gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). GABA influences the levels of two other neurotransmitters, dopamine and serotonin, producing a relaxation effect. Threonine - Threonine is another alcohol-containing amino acid that can not be produced by metabolism and must be taken in the diet. Threonine is an important component in the formation of protein, collagen, elastin and tooth enamel. It is also important for production of neurotransmitters and health of the nervous system. Tryptophan - Tryptophan is an essential amino acid formed from proteins during digestion by the action of proteolytic enzymes. Tryptophan is also a precursor for serotonin (a neurotransmitter) and melatonin (a neurohormone). Tryptophan may enhance relaxation and sleep, relieves minor premenstrual symptoms, soothes nerves and anxiety, and reduces carbohydrate cravings. Tyrosine - Tyrosine is metabolically synthesized from phenylalanine to become the para-hydroxy derivative of that important amino acid. Tyrosine is a precursor of the adrenal hormones epinephrine, norepinephrine, and the thyroid hormones, including thyroxine. L-tyrosine, through its effect on neurotransmitters, is used to treat conditions including mood enhancement, appetite suppression, and growth hormone (HGH) stimulation. Valine - Valine is a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) that is closely related to leucine and isoleucine both in structure and function. Valine is a constituent of fibrous protein in the body. As a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA), valine has been found useful in treatments involving muscle, mental, and emotional upsets, and for insomnia and nervousness. Valine may help treat malnutrition associated with drug addiction. | |

The health benefits of amino acids | |

| Amino acids are needed to build the various proteins used in the growth, repair, and maintenance of body tissues. Amino acids play innumerable roles in human health and disease. Alanine is necessary for the promotion of proper blood glucose levels from dietary protein. Alanine stimulates lymphocyte production and may help people who have immune suppression. Alanine strengthens the immune system by producing antibodies. L-arginine is used by the immune system to help regulate the activity of the thymus gland, which is responsible for manufacturing T lymphocytes. The body uses arginine to produce nitric oxide. Nitric oxide is an endogenous messenger molecule involved in a variety of endothelium-dependent physiological effects in the cardiovascular system. In the central nervous system, asparagine is needed to maintain a balance, preventing over nervousness or being overly calm. Aspartic acid can help protect the liver from some drug toxicity and the body from radiation. Carnosine is the water-soluble counterpart to vitamin E in protecting cell membranes from oxidative damage. L-carnosine supports healthy aging and cellular rejuvenation by its effects on two mechanisms: glycosylation and free radical damage. Cysteine strengthens the protective lining of the stomach and intestines, which may help prevent damage caused by aspirin and similar drugs. The health benefits of glutamine include immune system regulation, nitrogen shuttling, oxidative stress, muscle preservation, intestinal health, injuries, and much more. Glycine is an inhibitory amino acid with important functions centrally and peripherally. Glycine may be indicated to help alleviate the symptoms of spasticity. Histidine is known to be vital in the maintenance of the myelin sheaths surrounding nerves, particularly the auditory nerve and is used to treat some forms of hearing disability. Isoleucine is necessary for the optimal growth of infants and for nitrogen balance in adults. Leucine is used as a source for the synthesis of blood sugar in the liver during starvation, stress, and infection to aid in healing. Lysine is used in managing and preventing painful and unsightly herpes sores caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV). Methionine is both an antioxidant and lipotrope, meaning it helps remove fat from the liver. Phenylalanine is used to treated depression, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, menstrual cramps, Parkinson's disease, vitiligo, and cancer. Proline is an important component in certain medical wound dressings that use collagen fragments to stimulate wound healing. Serine is needed for the metabolism of fats and fatty acids, muscle growth, and a healthy immune system. Taurine helps regulate the contraction and pumping action of the heart muscle and it helps regulate blood pressure and platelet aggregation. Threonine may enhance immunity by assisting in the production of agents that fight viral infections. L-theanine reduces stress and anxiety without the tranquilizing effects found in many other calming supplements. Tryptophan is important for the production of serotonin. Increasing tryptophan may help to normalize sleep patterns. Tyrosine may act as an adaptogen, helping the body adapt to and cope with the effects of physical or psychological stress by minimizing the symptoms brought on by stress. As a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA), valine has been found useful in treatments involving muscle, mental, and emotional upsets, and for insomnia and nervousness. Creatine supplements fuels and enhances short bursts of high-energy exercise. Creatine prevents the body from relying solely on the process of glycolysis. Citrulline supports the body in optimizing blood flow through its conversion to l-arginine and then nitric oxide (NO). GABA has been used in the treatment of depression, manic-depressive (bipolar) disorder, seizures, premenstrual dysphoric (feeling depressed) disorder, and anxiety. Glutathione are necessary for supporting the immune system, glutathione is required for replication of the lymphocyte immune cells. |

Peptide

Article Link: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Peptide

More Details: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked together via peptide bonds and having a defined sequence. Peptides function primarily as signaling molecules in animals or as antibiotics in some lower organisms.

The number of amino acid molecules present in a peptide is indicated by a prefix. For example, a dipeptide has two amino acids; a tripeptidehas three. An oligopeptide contains a few molecules; a polypeptide contains many. Peptides generally contain fewer than 30 amino acid residues, while polypeptides contain as many as 4000. The distinction between polypeptides and proteins is largely academic and imprecise, and the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably. However, there is a movement within the scientific community to define proteins as polypeptides (or complexes of polypeptides) with three-dimensional structure.

In animals, peptides are involved in the complex coordination of the body, with three major classes of peptides involved in signaling:

Peptide hormones, which function as chemical messengers between cells. Growth hormone, for example, is involved in the general stimulation of growth, and insulin and glucagon are well known peptide hormones.

Neuropeptides, which are peptides found in neural tissue. Endorphins and enkephalins are neuropeptides that mimic the effects of morphine, inhibiting the transmission of pain signals. The peptides vasopressin and oxytoxin have been linked to social behaviors such as pair-bonding.

Growth factors, which play a role in regulating animal cell growth and differentiation.

Contents[hide] |

Human creativity has led to peptides being important tools for understanding protein structure and function. Peptide fragments are components of proteins that researchers use to identify or quantify the source protein. Often these fragments are the products of enzymatic degradation performed in the laboratory on a controlled sample, but they can also be forensic or paleontological samples that have been degraded by natural effects. Peptides also allow antibodies to be generated without the need to purify the protein of interest, by making antigenic peptides of sections of the protein.

The components of peptides

Summary of the formation of a peptide bond. Click on image to see the reaction.

Like proteins, peptides are built from combinations of 20 different amino acids, which are organic molecules composed of an amino group (-NH2), a carboxylic acid group (-COOH), and a unique R group, or side chain. Two amino acids (specifically, alpha-amino acids) are linked together by a peptide bond. A peptide bond is a chemical bond formed between two molecules when the carboxyl group of one amino acid reacts with the amino group of the other amino acid; the resulting CO-NH bond is called a peptide bond. An amino acid residue is what is left of an amino acid once it has coupled with another amino acid to form a peptide bond.

Peptides are then created by the polymerization of amino acids, a process in which amino acids are joined together in chains. Shorter strings of amino acids may be referred to as peptides, or, less commonly, oligopeptides.

Peptide synthesis

Peptides are synthesized from amino acids according to an mRNA template, which is itself synthesized from a DNA template inside the cell's nucleus. The precursors of ribosomal peptides are processed in several stages in the endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in "propeptides." These propeptides are then packaged into membrane-bound secretory vesicles, which can be released into the bloodstream in response to specific stimuli.

Nonribosomal peptides, found primarily in fungi, plants, and, unicellular organisms are synthesized using a modular enzyme complex (which functions much like a conveyor belt in a factory). All of these complexes are laid out in a similar fashion, and they may contain many different modules to perform a diverse set of chemical manipulations on the developing peptide. Nonribosomal peptides often have highly complex cyclic structures, although linear nonribosomal peptides are also common.

Some key peptide groups and their biological function

Peptides comprise the widest variety of signaling molecules in animals. The three major classes of peptides are peptide hormones,neuropeptides, and polypeptide growth factors. Many peptides are found in both the brain and non neural tissues. The blood-brain barrierprevents peptide hormones traveling in the blood from entering the brain, so that they do not interfere with the functioning of the central nervous system.

Peptide hormones

Peptide hormones are a class of peptides that function in living animals as chemical messengers from one cell (or group of cells) to another. Well-known peptide hormones include insulin, glucagon, and the hormones secreted from the pituitary gland, an endocrine gland about the size of a pea that sits in a small, bony cavity at the base of the brain. The latter include follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), growth hormone, and vasopressin. However, peptide hormones are produced by many different organs and tissues, including the heart, pancreas, and gastrointestinal tract.

Neuropeptides

A neuropeptide is any of the variety of peptides found in neural tissue. Approximately 100 different peptides are currently known to be released by different populations of neurons in the mammalian brain. Some neuropeptides act both as neurotransmitters in the nervous system and as neurohormones that act on distant cells.

Neurons use many different chemical signals to communicate information, including neurotransmitters, peptides, cannabinoids, and even some gases, like nitric oxide. Peptide signals play a role in information processing distinct from that of conventional neurotransmitters. While neurotransmitters generally affect the excitability of other neurons by depolarizing them or hyperpolarizing them, peptides have much more diverse effects; among other things, they can affect gene expression, local blood flow, and the formation of synapses.

Neurons very often produce both a conventional neurotransmitter (such as glutamate, GABA or dopamine) and one or more neuropeptides. Peptides are generally packaged in large dense-core vesicles, while the co-existing neurotransmitters are contained in small synaptic vesicles.

Vasopressin and oxytoxin

The neuropeptide Arginine vasopressin (AVP), also known as argipressin or antidiuretic hormone (ADH), is a hormone found in humans. It is mainly released when the body is low on water; it stimulates water reabsorption in the kidneys. It performs diverse actions when released in the brain, and has been implicated in memory formation, aggression, blood pressure regulation, and temperature regulation. Similar vassopressins are found in other mammalian species.

In recent years, there has been particular interest in the role of vasopressin in social behavior. It is thought that vasopressin, released into the brain during sexual activity, initiates and sustains patterns of activity that support the pair-bond between the sexual partners; in particular, vasopressin seems to induce the male to become aggressive towards other males. Evidence for this connection comes from experimental studies on several species which indicate that the precise distribution of vasopressin and vasopressin receptors in the brain is associated with species-typical patterns of social behavior. In particular, there are consistent differences between monogamous species and promiscuous species in the distribution of vasopressin receptors, and sometimes in the distribution of vasopressin-containing axons, even when closely-related species are compared. Moreover, studies involving either injecting vasopressin agonists into the brain or blocking the actions of vasopressin support the hypothesis that vasopressin is involved in aggression towards other males. There is also evidence that differences in the vasopressin receptor gene between individual members of a species might be predictive of differences in social behavior.

Oxytocin is a mammalian hormone involved in the stimulation of smooth muscle contraction that also acts as a neurotransmitter in the brain. In women, it is released mainly after distension of the cervix and vagina during labor, and after stimulation of the nipples, facilitating birth and breastfeeding, respectively.

Opioid peptides

Opioid peptides produced in the body include endorphins and enkephalins. Opioid peptides act as natural pain killers, or opiates, decreasing pain responses in the central nervous system.

Growth factors

Polypeptide growth factors control animal cell growth and differentiation. Nerve growth factor (or NGF) is involved in the development and survival of neurons, while platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) participates in blood clotting at the site of a wound. PDGF stimulates the spread of fibroblasts in the vicinity of the clot, facilitating the regrowth of the damaged tissue.

Given the role of polypeptide growth factors in controlling cell proliferation, abnormalities in growth factor signaling are the basis for a variety of diseases, including many types of cancer.

Peptides are an important research tool

Peptides have received prominence in molecular biology in recent times for several reasons:

Peptides allow researchers to generate antibodies in animals without the need to purify the protein of interest. The researcher can simply make antigenic peptides of sections of the protein.

Peptides have become instrumental in mass spectrometry, allowing the identification of proteins of interest based on peptide masses and sequences.

Peptides have recently been used in the study of protein structure and function. For example, synthetic peptides can be used as probes to determine where protein-peptide interactions occur.

Inhibitory peptides are also used in clinical research to examine the effects of peptides on the inhibition of cancer proteins and other diseases.

Peptide families

Below is a more detailed list of the major families of ribosomal peptides:

Vasopressin and oxytocin

Vasopressin

The Tachykinin peptides

Substance P

Kassinin

Neurokinin A

Eledoisin

Neurokinin B

Vasoactive intestinal peptides

VIP (Vasoactive intestinal peptide)

PACAP (Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide)

PHI 27

PHM 27

GHRH 1-24 (Growth hormone releasing hormone 1-24)

Secretin

Pancreatic polypeptide-related peptides

NPY

PYY (Peptide YY)

APP (Avian pancreatic polypeptide)

HPP (Human pancreatic polypeptide)

Opioid peptides

Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) Peptides

The Enkephalin pentapeptides

The Prodynorphin peptides

Calcitonin peptides

Amylin

AGG01

Protein

Article Link: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/what-should-you-eat/protein/

More Details: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protein

Protein is found throughout the body—in muscle, bone, skin, hair, and virtually every other body part or tissue. It makes up the enzymes that power many chemical reactions and the hemoglobin that carries oxygen in your blood. At least 10,000 different proteins make you what you are and keep you that way.

The Institute of Medicine recommends that adults get a minimum of 0.8 grams of protein for every kilogram of body weight per day (or 8 grams of protein for every 20 pounds of body weight). (1) The Institute of Medicine also sets a wide range for acceptable protein intake—anywhere from 10 to 35 percent of calories each day. Beyond that, there’s relatively little solid information on the ideal amount of protein in the diet or the healthiest target for calories contributed by protein.

In the United States, the recommended daily allowance of protein is 46 grams per day for women over 19 years of age, and 56 grams per day for men over 19 years of age. (2)

Around the world, millions of people don’t get enough protein. Protein malnutrition leads to the condition known as kwashiorkor. Lack of protein can cause growth failure, loss of muscle mass, decreased immunity, weakening of the heart and respiratory system, and death.

All Protein Isn’t Alike

Protein is built from building blocks called amino acids. Our bodies make amino acids in two different ways: Either from scratch, or by modifying others. A few amino acids (known as the essential amino acids) must come from food.

Animal sources of protein tend to deliver all the amino acids we need.

Other protein sources, such as fruits, vegetables, grains, nuts and seeds, lack one or more essential amino acids.

Vegetarians need to be aware of this. People who don’t eat meat, fish, poultry, eggs, or dairy products need to eat a variety of protein-containing foods each day in order to get all the amino acids needed to make new protein.

The Protein Package

Some high-protein foods are healthier than others because of what comes along with the protein: healthy fats or harmful ones, beneficial fiber or hidden salt. It’s this protein package that’s likely to make a difference for health. For example, a 6-ounce broiled porterhouse steak is a great source of protein—about 40 grams worth. But it also delivers about 12 grams of saturated fat. (3) For someone who eats a 2,000 calorie per day diet, that’s more than 60 percent of the recommended daily intake for saturated fat.

A 6-ounce ham steak has only about 2.5 grams of saturated fat, but it’s loaded with sodium—2,000 milligrams worth, or about 500 milligrams more than the daily sodium max.

6-ounces of wild salmon has about 34 grams of protein and is naturally low in sodium, and contains only 1.7 grams of saturated fat. (3) Salmon and other fatty fish are also excellent sources of omega-3 fats, a type of fat that’s especially good for the heart. Alternatively, a cup of cooked lentils provides about 18 grams of protein and 15 grams of fiber, and it has virtually no saturated fat or sodium. (3)

Protein and Chronic Diseases

Proteins in food and the environment are responsible for food allergies, which are overreactions of the immune system. Beyond that, relatively little evidence has been gathered regarding the effect of the amount of dietary protein on the development of chronic diseases in healthy people.

However, there’s growing evidence that high-protein food choices do play a role in health—and that eating healthy protein sources like fish, chicken, beans, or nuts in place of red meat (including processed red meat) can lower the risk of several diseases and premature death. (2, 4-8, 25)

Cardiovascular disease

Research conducted at Harvard School of Public Health has found that eating even small amounts of red meat, especially processed red meat, on a regular basis is linked to an increased risk of heart disease and stroke, and the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease or any other cause. (4, 6, 8) Conversely, replacing red and processed red meat with healthy protein sources such as poultry, fish, or beans seems to reduce these risks.

One investigation followed 120,000 men and women in the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study for more than two decades. (6) For every additional 3-ounce serving of unprocessed red meat the study participants consumed each day, their risk of dying from cardiovascular disease increased by 13 percent.

Processed red meat was even more strongly linked to dying from cardiovascular disease—and in smaller amounts: Every additional 1.5 ounce serving of processed red meat consumed each day—equivalent to one hot dog or two strips of bacon—was linked to a 20 percent increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease death.

Cutting back on red meat could save lives: the researchers estimated that if all the men and women in the study had reduced their total red and processed red meat intake to less than half a serving a day, one in ten cardiovascular disease deaths would have been prevented.

In terms of the amount of protein consumed, there’s evidence that eating a high-protein diet may be beneficial for the heart, as long as the protein comes from a healthy source.

A 20-year prospective study of over 80,000 women found that those who ate low-carbohydrate diets that were high in vegetable sources of fat and protein had a 30 percent lower risk of heart disease compared with women who ate high-carbohydrate, low-fat diets. Diets were given low-carbohydrate scores based on their intake of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. (9) However, eating a low-carbohydrate diet high in animal fat or protein did not offer such protection.

Further evidence of the heart benefits of eating healthy protein in place of carbohydrate comes from a randomized trial known as the Optimal Macronutrient Intake Trial for Heart Health (OmniHeart). A healthy diet that replaced some carbohydrate with healthy protein (or healthy fat) did a better job of lowering blood pressure and harmful low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol than a similarly healthy, higher carbohydrate diet. (10)

Similarly, the “EcoAtkins” weight loss trial compared a low-fat, high -carbohydrate, vegetarian diet to a low-carbohydrate vegan diet that was high in vegetable protein and fat. Though weight loss was similar on the two diets, study participants on the high protein diet saw improvements in blood lipids and blood pressure. (11)

A more recent study generated headlines because it had the opposite result. In that study, Swedish women who ate low-carbohydrate, high-protein diets had higher rates of cardiovascular disease and death than those who ate lower-protein, higher-carbohydrate diets. (12) But the study, which assessed the women’s diets only once and then followed them for 15 years, did not look at what types of carbohydrates or what sources of protein these women ate. That was important because most of the women’s protein came from animal sources.

Diabetes

Again, protein quality matters more than protein quantity when it comes to diabetes risk (23)

A recent study found that people who ate diets high in red meat, especially processed red meat, had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes than those who rarely ate red or processed meat. (7) For each additional serving a day of red meat or processed red meat that study participants ate, their risk of diabetes rose 12 and 32 percent, respectively.

Substituting one serving of nuts, low-fat dairy products, or whole grains for a serving of red meat each day lowered the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by an estimated 16 to 35 percent.

Another study also shows that red meat consumption may increase risk of type 2 diabetes. Researchers found that people who started eating more red meat than usual were found to have a 50% increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes during the next four years, and researchers also found that those who reduced red meat consumption lowered their type 2 diabetes risk by 14% over a 10-year follow-up period.

More evidence that protein quality matters comes from a 20-year study that looked at the relationship between low-carbohydrate diets and type 2 diabetes in women. Low-carbohydrate diets that were high in vegetable sources of fat and protein modestly reduced the risk of type 2 diabetes. (13) But low-carbohydrate diets that were high in animal sources of protein or fat did not show this benefit.

For type 1 diabetes (formerly called juvenile or insulin-dependent diabetes), proteins found in cow’s milk have been implicated in the development of the disease in babies with a predisposition to the disease, but research remains inconclusive. (14, 15)

Cancer

When it comes to cancer, protein quality again seems to matter more than quantity. Research on the association between protein and cancer is ongoing, but some data shows that eating a lot of red meat and processed meat is linked to an increased risk of colon cancer. (2)

In the Nurse’s Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, every additional serving per day of red meat or processed red meat was associated with a 10 and 16 percent higher risk of cancer death, respectively. (6)

A 2014 study showed that higher consumption of red meat during adolescence was associated with premenopausal breast cancer, suggesting that choosing other protein sources in adolescence may decrease premenopausal breast cancer risk. (22)

People should aim to reduce overall consumption of red meat and processed meat, but when you do opt to have it, go easy on the grill. High-temperature grilling creates potentially cancer-causing compounds in meat, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic amines. You don’t have to stop grilling, but try these tips for healthy grilling from the American Institute of Cancer Research: Marinate meat before grilling it, partially pre-cook meat in the oven or microwave to reduce time on the grill, and grill over a low flame.

In October 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO)’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) announced that consumption of processed meat is “carcinogenic to humans,” and that consumption of red meat is “probably carcinogenic to humans.” (24)

The IARC Working Group, comprised of 22 scientists from ten countries, evaluated over 800 studies.

Conclusions were primarily based on the evidence for colorectal cancer. Data also showed positive associations between processed meat consumption and stomach cancer, and between red meat consumption and pancreatic and prostate cancer. (24)

Osteoporosis

Digesting protein releases acids into the bloodstream, which the body usually neutralizes with calcium and other buffering agents. Eating lots of protein, then, requires a lot of calcium – and some of this may be pulled from bone.

Following a high-protein diet for a long period of time could weaken bone. In the Nurses’ Health Study, for example, women who ate more than 95 grams of protein a day were 20 percent more likely to have broken a wrist over a 12-year period when compared with those who ate an average amount of protein (less than 68 grams a day). (16) This area of research is still controversial, however, and the findings have not been consistent. Some studies suggest that increasing protein increases risk of fractures; others have linked high-protein diets with increased bone-mineral density, and thus stronger bones. (17-19)

Protein and Weight Control

The same high-protein foods that are good choices for disease prevention may also help with weight control. Researchers at Harvard School of Public Health followed the diet and lifestyle habits of 120,000 men and women for up to 20 years, looking at how small changes contributed to weight gain over time. (20)

Those who ate more red and processed meat over the course of the study gained more weight, about one extra pound every four years, while those who ate more nuts over the course of the study gained less weight, about a half pound less every four years.

One study showed that eating approximately one daily serving of beans, chickpeas, lentils or peas can increase fullness, which may lead to better weight management and weight loss. (21)

There’s no need to go overboard on protein. Though some studies show benefits of high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets in the short term, avoiding fruits and whole grains means missing out on healthful fiber, vitamins, minerals, and other phytonutrients.

Hydrolysis

Article Link: http://www.chemistryexplained.com/Hy-Kr/Hydrolysis.html

More Details: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis literally means reaction with water. It is a chemical process in which a molecule is cleaved into two parts by the addition of a molecule of water. One fragment of the parent molecule gains a hydrogen ion (H + ) from the additional water molecule. The other group collects the remaining hydroxyl group (OH − ). To illustrate this process, some examples from real life and actual living systems are discussed here.

The most common hydrolysis occurs when a salt of a weak acid or weak base (or both) is dissolved in water. Water autoionizes into negative hydroxyl ions and hydrogen ions. The salt breaks down into positive and negative ions. For example, sodium acetate dissociates in water into sodium and acetate ions. Sodium ions react very little with hydroxyl ions whereas acetate ions combine with hydrogen ions to produce neutral acetic acid, and the net result is a relative excess of hydroxyl ions, causing a basic solution.

However, under normal conditions, only a few reactions between water and organic compounds occur. Generally, strong acids or bases must be added in order to achieve hydrolysis where water has no effect. The acid or base is considered a catalyst . They are meant to speed up the reaction, but are recovered at the end of it.

Acid–base-catalyzed hydrolyses are very common; one example is the hydrolysis of amides or esters . Their hydrolysis occurs when the nucleophile (a nucleus-seeking agent, e.g., water or hydroxyl ion) attacks the carbon of the carbonyl group of the ester or amide. In an aqueous base, hydroxyl ions are better nucleophiles than dipoles such as water. In acid, the carbonyl group becomes protonated, and this leads to a much easier nucleophilic attack. The products for both hydrolyses are compounds with carboxylic acid groups.

Perhaps the oldest example of ester hydrolysis is the process called saponification. It is the hydrolysis of a triglyceride (fat) with an aqueous base such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH). During the process, glycerol, also commercially named glycerin, is formed, and the fatty acids react with the base, converting them to salts. These salts are called soaps, commonly used in households.

Moreover, hydrolysis is an important process in plants and animals, the most significant example being energy metabolism and storage. All living cells require a continual supply of energy for two main purposes: for the biosynthesis of small and macromolecules, and for the active transport of ions and molecules across cell membranes. The energy derived from the oxidation of nutrients is not used directly but, by means of a complex and long sequence of reactions, it is channeled into a special energy-storage molecule, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) .

The ATP molecule contains pyrophosphate linkages (bonds formed when two phosphate units are combined together) that release energy when needed. ATP can be hydrolyzed in two ways: the removal of terminal phosphate to form adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate, or the removal of a terminal diphosphate to yield adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and pyrophosphate. The latter is usually cleaved further to yield two phosphates. This results in biosynthesis reactions, which do not occur alone, that can be driven in the direction of synthesis when the phosphate bonds are hydrolyzed.

In addition, in living systems, most biochemical reactions, including ATP hydrolysis, take place during the catalysis of enzymes. The catalytic action of enzymes allows the hydrolysis of proteins, fats, oils, and carbohydrates. As an example, one may consider proteases, enzymes that aid digestion by hydrolyzing peptide bonds in proteins. They catalyze the hydrolysis of interior peptide bonds in peptide chains, as opposed to exopeptidases, another class of enzymes, that catalyze the hydrolysis of terminal peptide bonds, liberating one free amino acid at a time.

However, proteases do not catalyze the hydrolysis of all kinds of proteins. Their action is stereo-selective: Only proteins with a certain tertiary structure will be targeted. The reason is that some kind of orienting force is needed to place the amide group in the proper position for catalysis. The necessary contacts between an enzymeand its substrates (proteins) are created because the enzyme folds in such a way as to form a crevice into which the substrate fits; the crevice also contains the catalytic groups. Therefore, proteins that do not fit into the crevice will not be hydrolyzed. This specificity preserves the integrity of other proteins such as hormones, and therefore the biological system continues to function normally.

Read more: http://www.chemistryexplained.com/Hy-Kr/Hydrolysis.html#ixzz5FNjh4pjw