姓 名: 王珊珊 专 业:英 语 年级、班级:12级3班

学 号:12301041 作业日期:2013.12.09

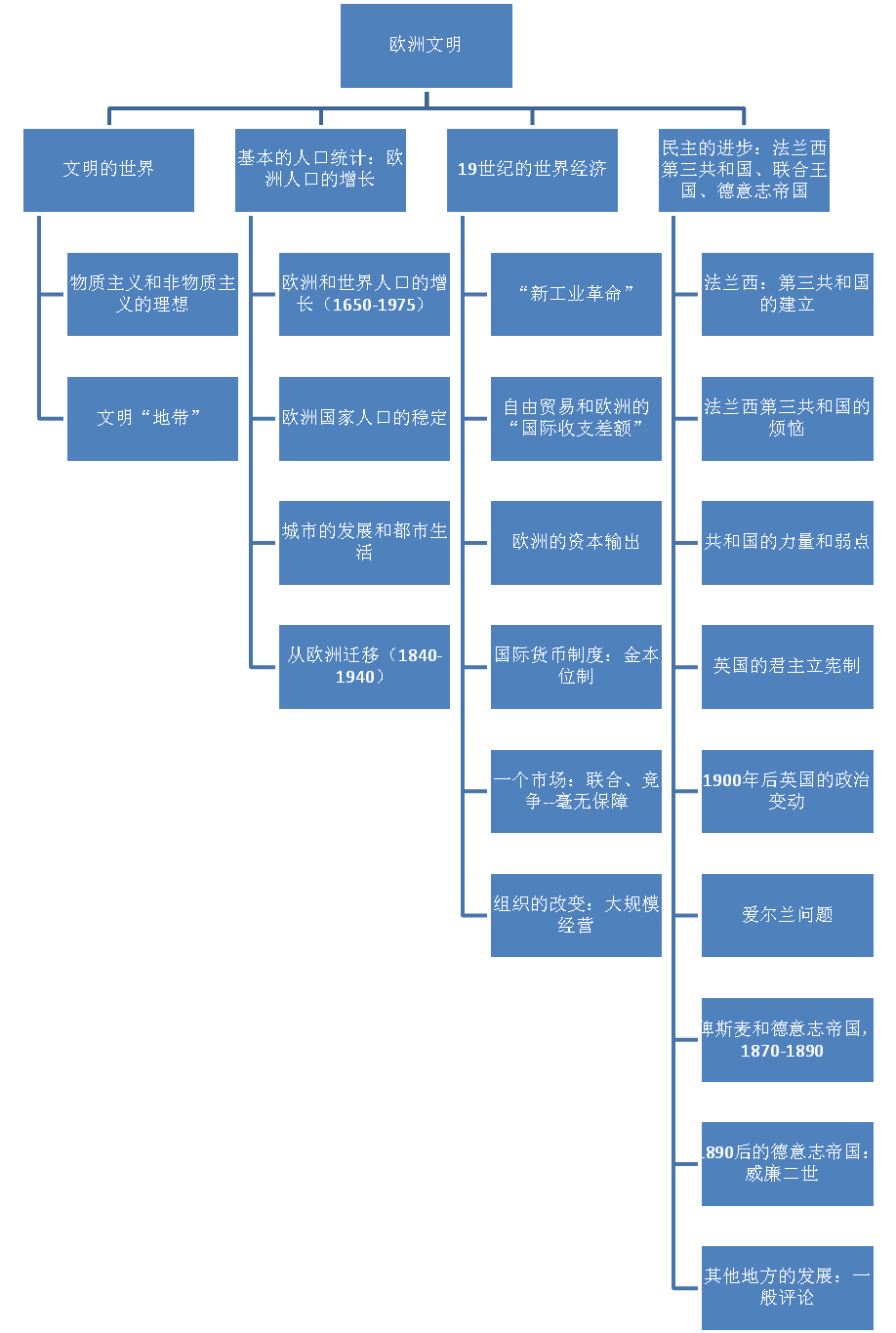

章 节: Chapter 11 Europe Civilization, 1871---1914: Economy and Politics

作业要求:Write a summary of Europe Civilization, 1871---1914: Economy and Politics in about1000--1200 words in English.

(体例说明:中文字体为宋体,英文为Arail,五号字,行距1.5倍)

Summary of Europe Civilization, 1871---1914: Economy and Politics

European civilization achieved its greatest power in global politics, developed its leading role in the global economy, and also exerted its maximum influence upon peoples outside Europe. The years 1871 to 1914 were marked by unparalleled material and industrial growth; international peace; domestic stability; the advance of constitutional, representative, and democratic government; and continued faith in science, reason and progress. There are still new trends to undermine the liberal premises and tenets of Europe civilization. A new wave of European imperialism spread across Africa and Asia, creating new colonial empires, new global economic connections, and new international and cultural conflicts. We complete the era into different thematic strands, including the modern “civilized world”, basic demography: the increase of the Europeans, the world economy of the nineteenth Century, the advance of democracy.

In the first part, the ideals of European or western civilization were in part materialistic. Europeans and Westerners had a higher standard of living, ate and dressed more adequately, slept in softer beds, and had more satisfactory sanitary facilities. They also possessed ocean liners, railroads and streetcars and after about 1800, telephones and electric lights. But the ideal of civilization was by no means exclusively materialistic. Knowledge as such, correct or truthful knowledge, was held to be a civilized attainment. Other indices worked out by sociologist to show the level of advancement of a given society. One of these is the death rate , or a number of persons per thousand of population who die each year. In some European countries and United States, the true death rate is known to have fallen from 25 before 1850, to 19 in 1914 and 18 in the 1930s, and stood stabilized about 18 before the Second World War. Death rates in countries “not modern” usually run over 40 in favorable times. There are several indexes, including infant mortality, life expectancy, literacy rate and the productivity of labor, or amount produced by one worker in a given expenditure of time. The essence of civilized living doubtless is in the intangibles, in the way in which people use their minds and in the attitudes they form toward others or toward the conditions and planing of their own lives. But they are not always agreed upon by persons of different cultures or ideologies. The zone of civilization centered in a certain region of Europe. There are two Europes, an inner zone and an outer. The inner zone included not only Great Britain but Belgium, Germany, France northern Italy, and the western portions of the Austrain Empire. The outer zone included most of Ireland, most of the Iberian and Italian peninsulas, and all Europe east of what was then Germany, Bohemia, and Austrain proper. The third zone included the immense reaches of Asia and Africa, all viewed as “backward” by the standards or cultural assumptions of Europe.

The second part deals with basic demography: the increase of the Europeans. It was Europe that grew the most in population in the three centuries following 1650. In Europe, the organized sovereign states, as established in the 17th century, put an end to a long period of civil wars, stopping the chronic violence and marauding. There are many other causes, including liberation from certain endemic afflictions, beginning with the subsiding of bubonic plague in the 17th century and the use of vaccination against smallpox in the 18th agricultural improvement produced more food. The improvement of transportation made it possible to move the food into areas of temporary shortage. The Industrial Revolution made larger populations could subsist in Europe by improving food from overseas. Europe increased fourfold, and the total number of Europeans, including the descendants of those who migrated to other continents, multiplied fivefold. The stabilization and relative decline of the European population followed from a fall in the birth rate. The reduced birth is not a mere dry statistical item, nor does it affect populations merely in the mass. Historical demographers have detected a “European family pattern” as far back as the 17th century. In the great cities of the 19thcentury, in which standards of life for the working classes often collapsed, the effect might at first be a proliferation of offspring. The effects of the small family system upon total population become manifest only slowly. Rural populations in the inner zone became dense. The 19th century city was mostly the child of the railroad, for with the railroads it became possible for the first time to concentrate manufacturing in large towns, to which bulky goods such as foods and fuel could now be moved in great volume. Almost 60 million people left altogether, of whom possibly a fifth sooner or later returned.

The third part talks about the world economy of the nineteenth century. The Industrial Revolution and the global economy entered upon a new phase. The use of steam power, the growth of the textile and metallurgical industries, and the advent of the railroad had characterized the early part of the century. It was Britain in the mid-nineteenth century, then the workshop of the world, that had inaugurated the movement toward free trade. Broadly speaking, the great economic accomplishment of Europe before 1914 was to create a system by which the huge imports used by industrial Europe could be acquired and paid for. Europe also exported the capital that enabled the new settlers to develop productive economies. The international economy rested upon an international money system, based in turn upon the almost universal acceptance of the the gold standard. The creation of an integrated world market, the financing and building up of countries outside of Europe, and the consequent feeding and support of Europe’s increasing population were the great triumphs of the 19th century system of unregulated capitalism. A great change came over capitalism itself about 1880. Formally characterized by a large number of small units, small businesses run by individuals, partnerships, or small companies, it was increasingly characterized by large and impersonal corporations.

The last part of this chapter focuses on the advance of democracy: third French Republic, United Kingdom and German Empire. In the years from 1815 European political life had been marked by literal agitation for constitutional government, representative assemblies, responsible ministries, and guarantees of individual liberties. In France the democratic republic was not easily established, and its troubled early years left deep cleavages within the country. It will be recalled that in September 1870, when the empire of Napoleon Third revealed its helplessness in the Franco-Prussian War, insurrectionaries in Paris, as in 1792 and 1848, again proclaimed the Republic. Yet the Third Republic was precarious. The government had changed so often since 1789 that all forms of government seemed to be transitory. The British constitutional monarchy in the half-century before 1914 was the great exemplar of reasonable, orderly, and peaceable self-government through parliamentary methods. At turn of the century important changes were discernible on the British political scene. Labor emerged as an independent political force, the Labour party itself being organized shortly after 1900. The rise of labor had a deep impact upon the Liberal party and indeed upon liberalism. British suffered from one of the most bitter minorities conflicts in Europe---what the British called the Irish Question. The German Empire , as put together by Bismarck in 1871 with William the First, king of Prussia, as Kaiser, was a federation of monarchies, a union of 25 German states, in which the weight of monarchical Prussia, the Prussia army, and the Prussian landed aristocracy was preponderant. It developed neither the strong constitutionalism of England nor the democratic equality that was characteristic of France.