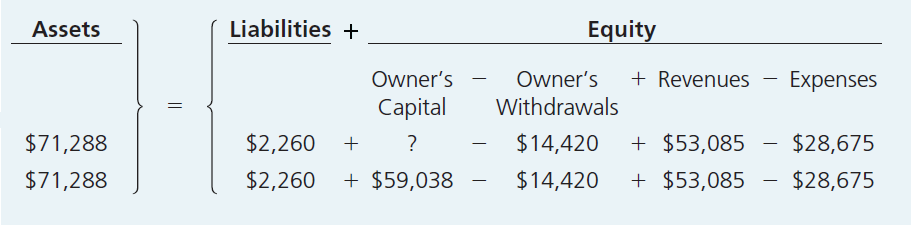

The accounting equation must always balance.

Most textbook examples show companies that are profitable from the very beginning and always have positive equity balances. Although not illustrated in many textbooks, stockholders’equity can be negative if liabilities exceed assets, but the equation would still balance.

For example, a company could have $100 of assets, $150 of liabilities, and $(50) of equity,and the equation would equal $100 on each side. This is not a good position tobe in, but is not unusual in the business world. You could also have a transaction that affects only one side of the equation (left or right), but the equation would still balance. For example, a transaction could increase one asset and decrease another asset and the equation would balance with no effecton liabilities and equity. A company that purchases supplies with cash would experience this.