In this section, we introduce the Java mechanism that enables us to create user-defined data types. We consider a range of examples, from charged particles and complex numbers to turtle graphics and stock accounts.

Basic elements of a data type.

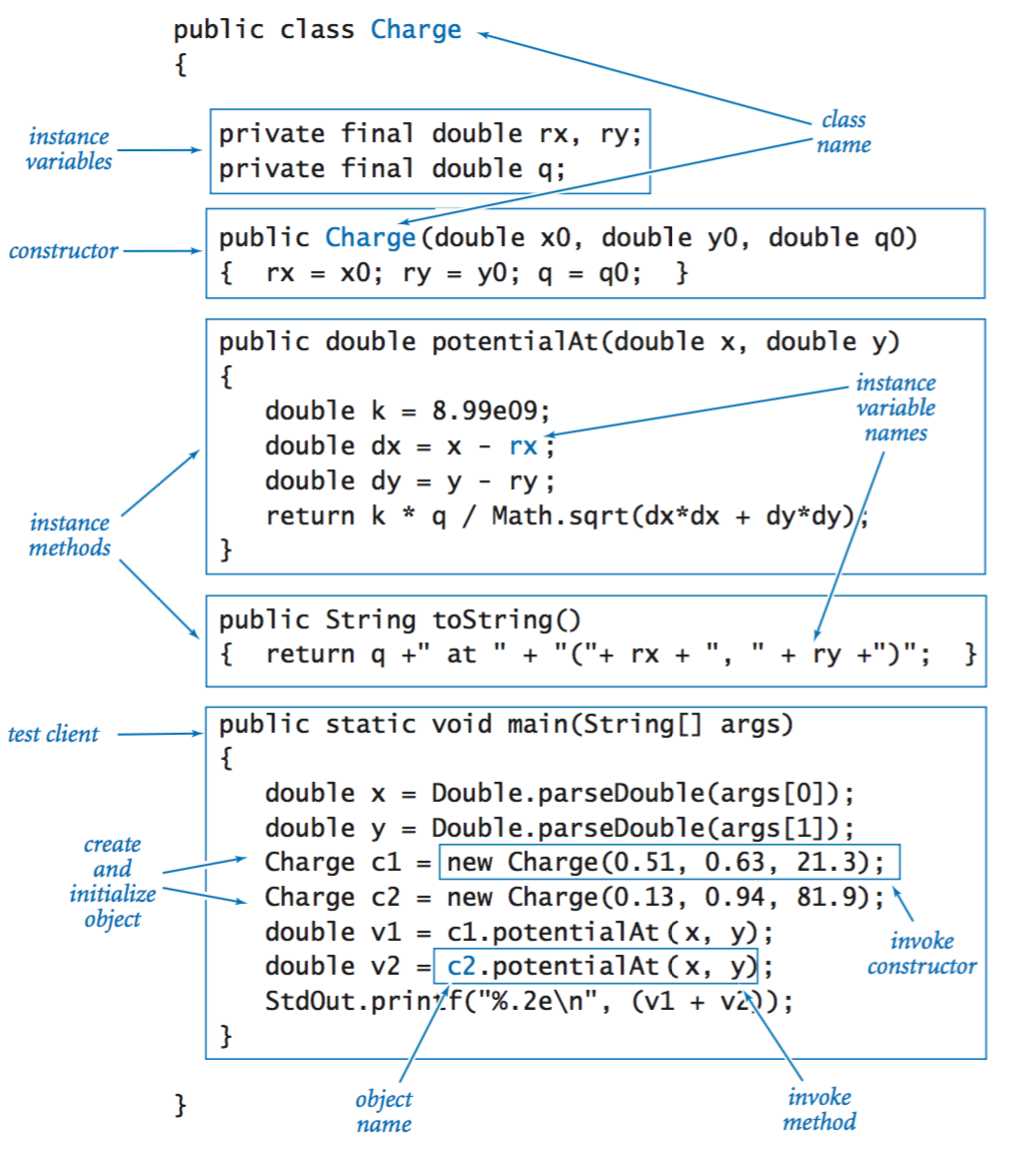

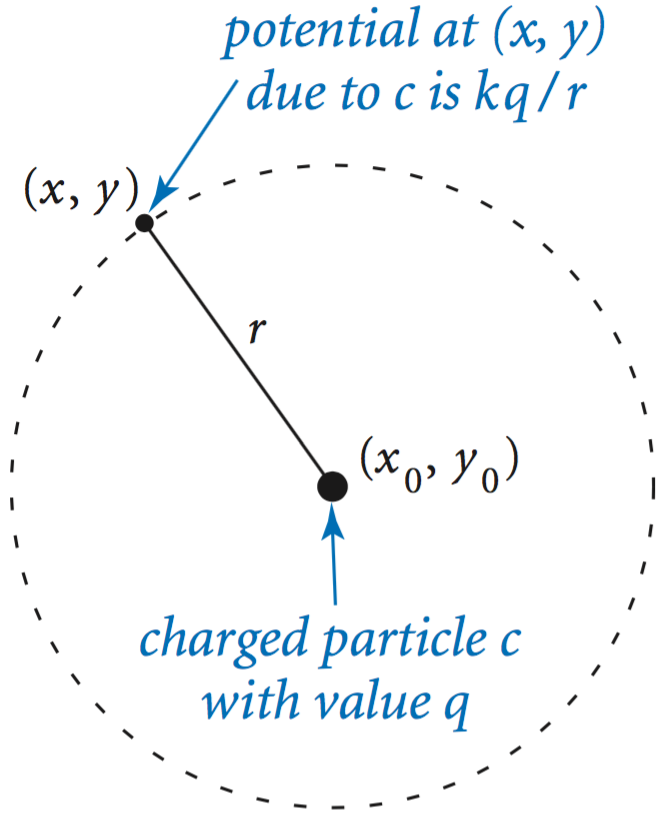

To illustrate the process, we define in Charge.java a data type for charged particles. Coulomb’s law tells us that the electric potential at a point due to a given charged particle is , where is the charge value, is the distance from the point to the charge, and is the electrostatic constant.

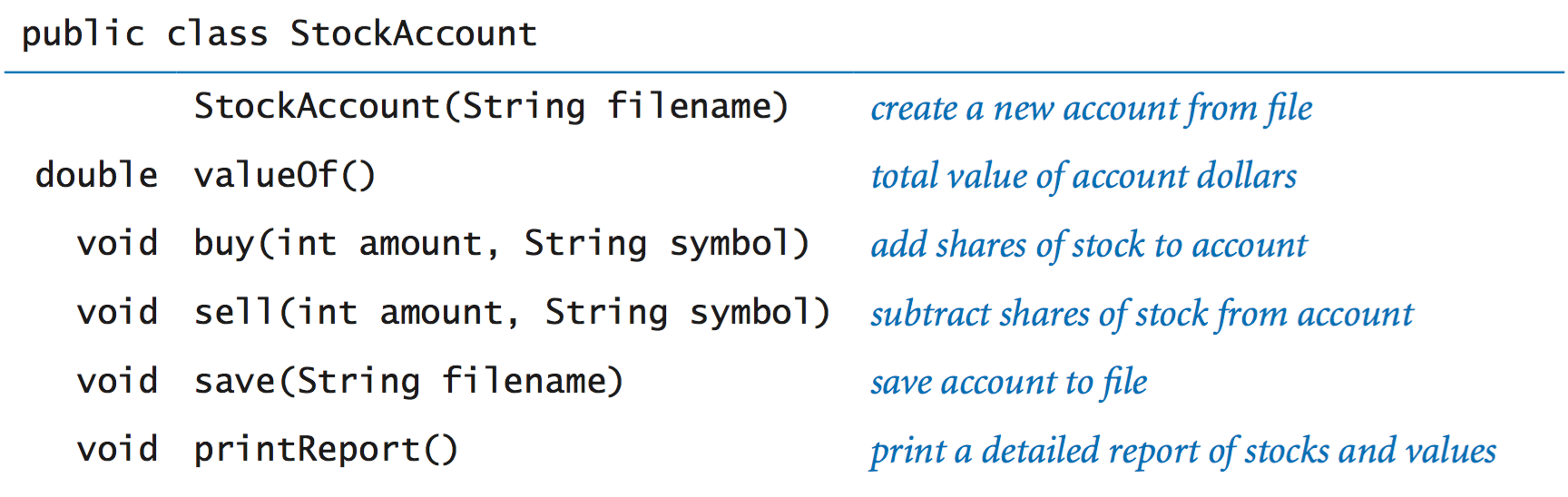

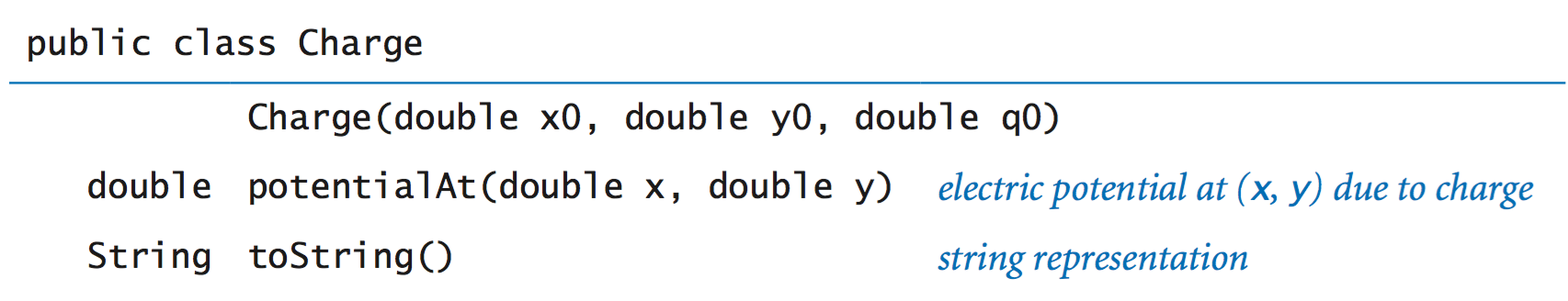

API. The application programming interface is the contract with all clients and, therefore, the starting point for any implementation.

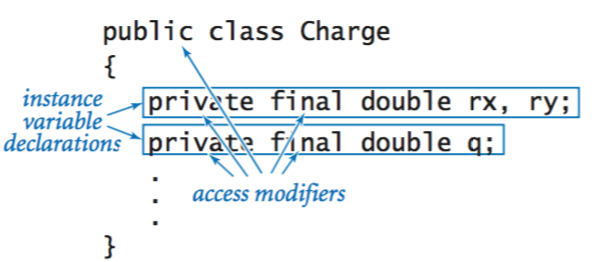

Class. In Java, you implement a data type in a class. As usual, we put the code for a data type in a file with the same name as the class, followed by the .java extension.

Access modifiers. We designate every instance variable and method within a class as either public (this entity is accessible by clients) orprivate (this entity is not accessible by clients). The final modifier indicates that the value of the variable will not change once it is initialized—its access is read-only.

Instance variables. We declare instance variables to represent the data-type values in the same way as we declare local variables, except that these declarations appear as the first statements in the class, not inside main() or any other method. For Charge, we use threedouble variables—two to describe the charge’s position and one to describe the amount of charge.

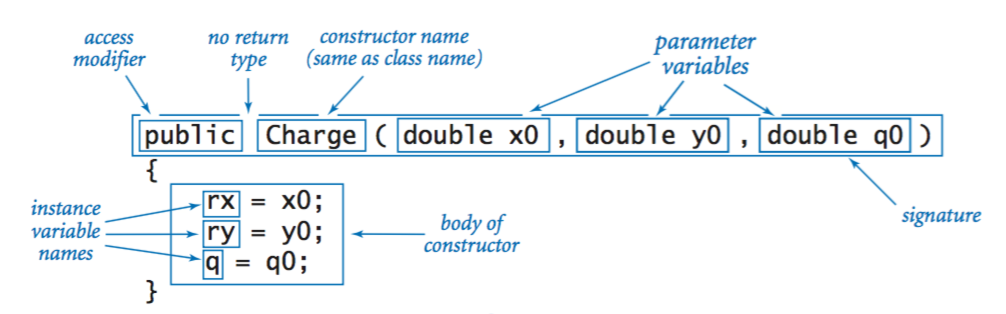

Constructors. A constructor is a special method that creates an object and provides a reference to that object. Java automatically invokes a constructor when a client program uses the keyword new. Each time that a client invokes a constructor, Java automatically

Allocates memory for the object

Invokes the constructor code to initialize the instance variables

Returns a reference to the newly created object

The constructor in Charge is typical: it initializes the instance variables with the values provided by the client as arguments.

Instance methods. To implement instance methods, we write code that is precisely like code for implementing static methods. The one critical distinction is that instance methods can perform operations on instance variables.

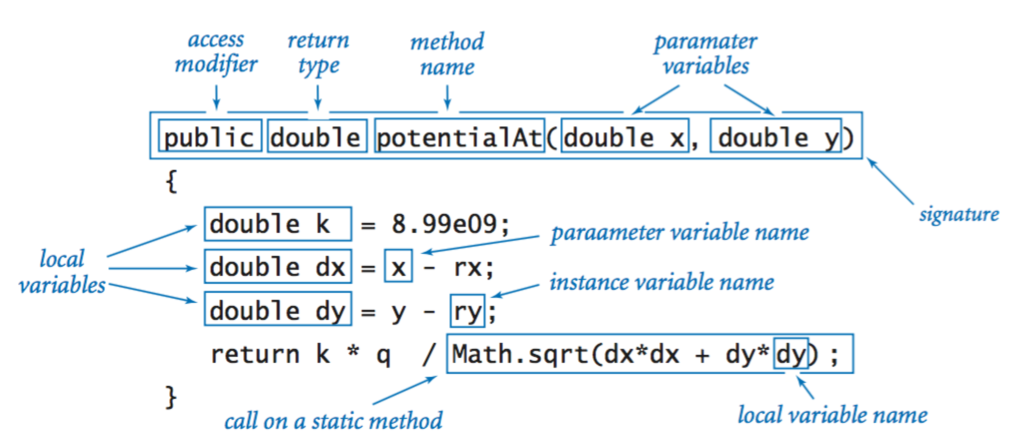

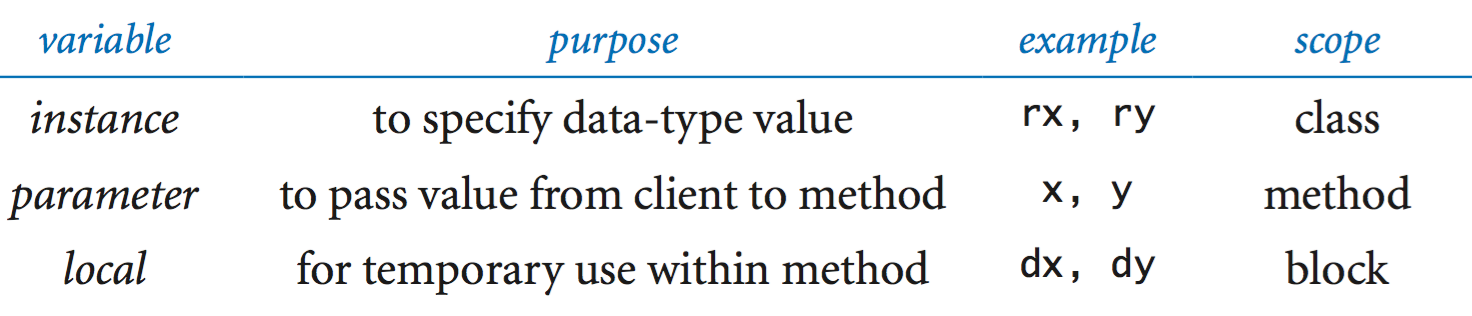

Variables within methods. The Java code we write to implement instance methods uses three kinds of variables. Parameter variables and local variables are familiar. Instance variables are completely different: they hold data-type values for objects in a class.

Each object in the class has a value: the code in an instance method refers to the value for the object that was used to invoke the method. For example, when we write c1.potentialAt(x, y), the code in potentialAt() is referring to the instance variables for c1.

Test client. Each class can define its own main() method, which we reserve for unit testing. At a minimum, the test client should call every constructor and instance method in the class.

In summary, to define a data type in a Java class, you need instance variables, constructors, instance methods, and a test client.

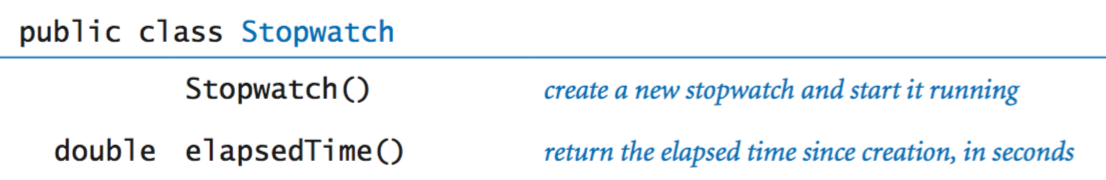

Stopwatch.

Stopwatch.java implements the following API:

It is a stripped-down version of an old-fashioned stopwatch. When you create one, it starts running, and you can ask it how long it has been running by invoking the method elapsedTime().

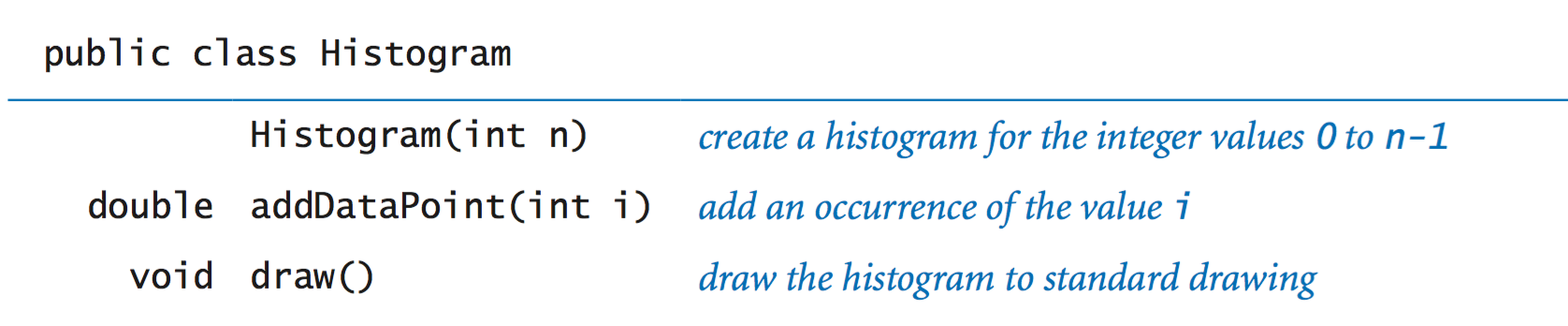

Histogram.

Histogram.java is a data type to visualize data using a familiar plot known as a histogram. For simplicity, we assume that the data consists of a sequence of integer values between 0 and n−1. A histogram counts the number of times each value appears and plots a bar for each value (with height proportional to its frequency). The following API describes the operations:

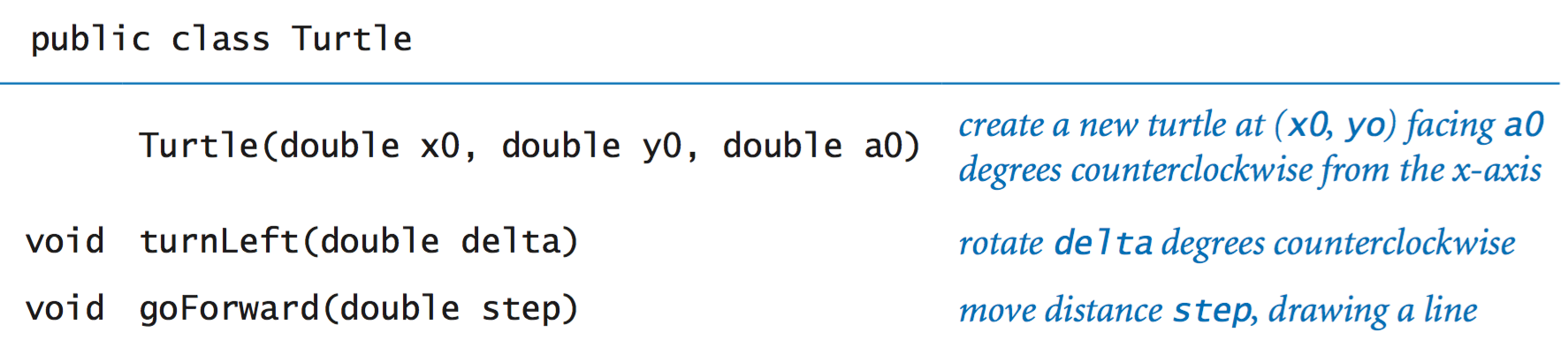

Turtle graphics.

Turtle.java is a mutable type for turtle graphics, in which we command a turtle to move a specified distance in a straight line, or rotate (counterclockwise) a specified number of degrees.

Here are a few example clients:

Regular n-gons. Ngon.java takes a command-line argument n and draws a regular n-gon using turtle graphics. By taking n to a sufficiently large value, we obtain a good approximation to a circle.

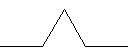

Recursive graphics. Koch.java takes a command-line argument n and draws a Koch curve of order n. A Koch curve of order order 0 is a line segment. To form a Koch curve of order n:

Draw a Koch curve of order n−1

Rotate 60° counterclockwise

Draw a Koch curve of order n−1

Rotate 120° clockwise

Draw a Koch curve of order n−1

Rotate 60° counterclockwise

Draw a Koch curve of order n−1

Below are the Koch curves of order 0, 1, 2, and 3.

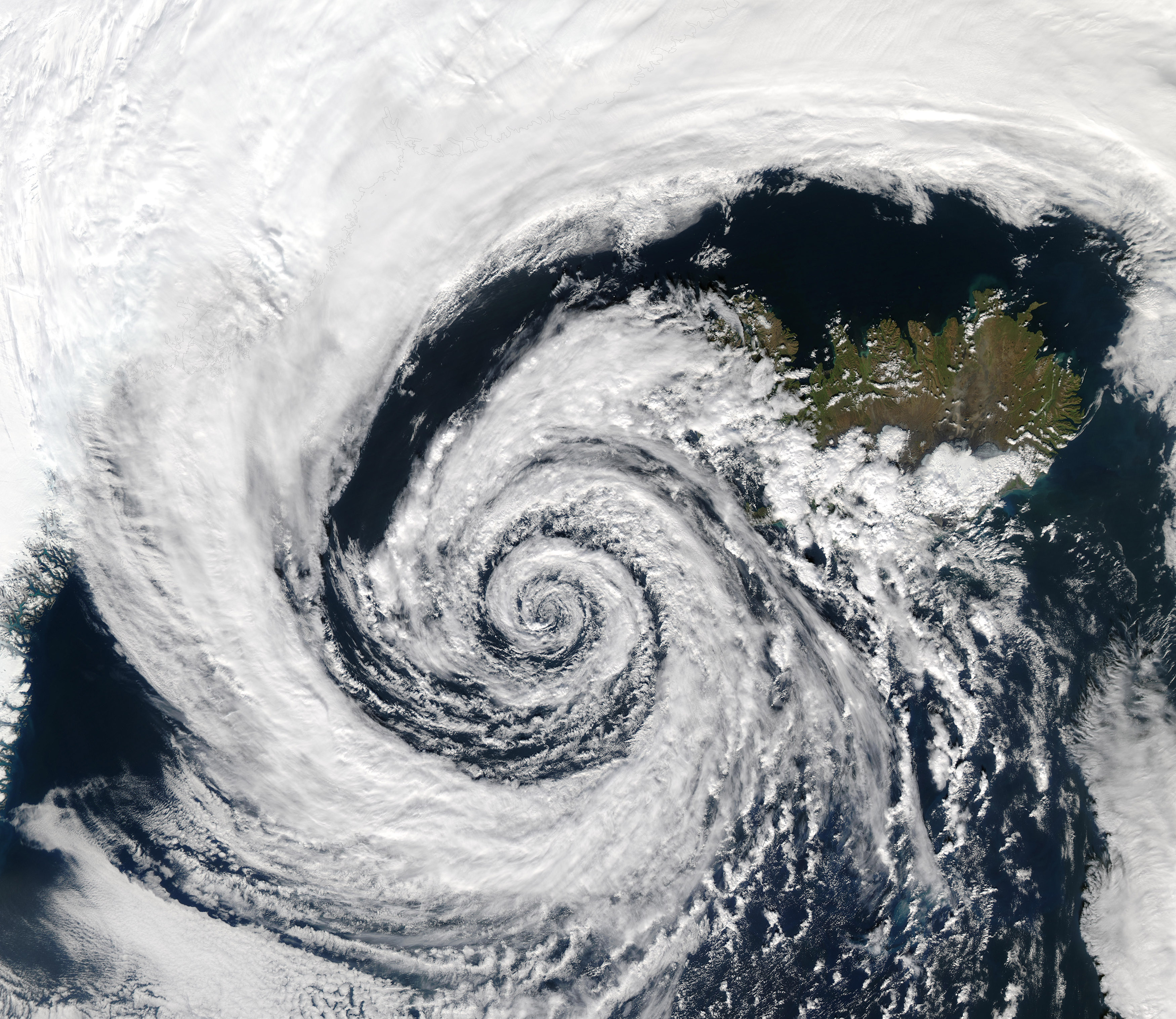

Spira mirabilis. Spiral.java takes an integer n and a decay factor as command-line arguments, and instructs the turtle to alternately step and turn until it has wound around itself 10 times. This produces a geometric shape known as a logarithmic spiral, which arise frequently in nature. Three examples are depicted below: the chambers of a nautilus shell, the arms of a spiral galaxy, and the cloud formation in a tropical storm.

Brownian motion. DrunkenTurtle.java plots the path followed by a disoriented turtle, who alternates between moving forward and turning in a random direction. This process is known as Brownian motion. DrunkenTurtles.java plots many such turtles, all of whom wander around.

Complex numbers.

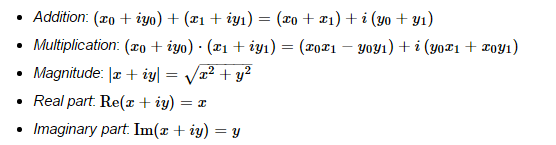

A complex number is a number of the form x + iy, where x and y are real numbers and i is the square root of −1. The basic operations on complex numbers are to add and multiply them, as follows:

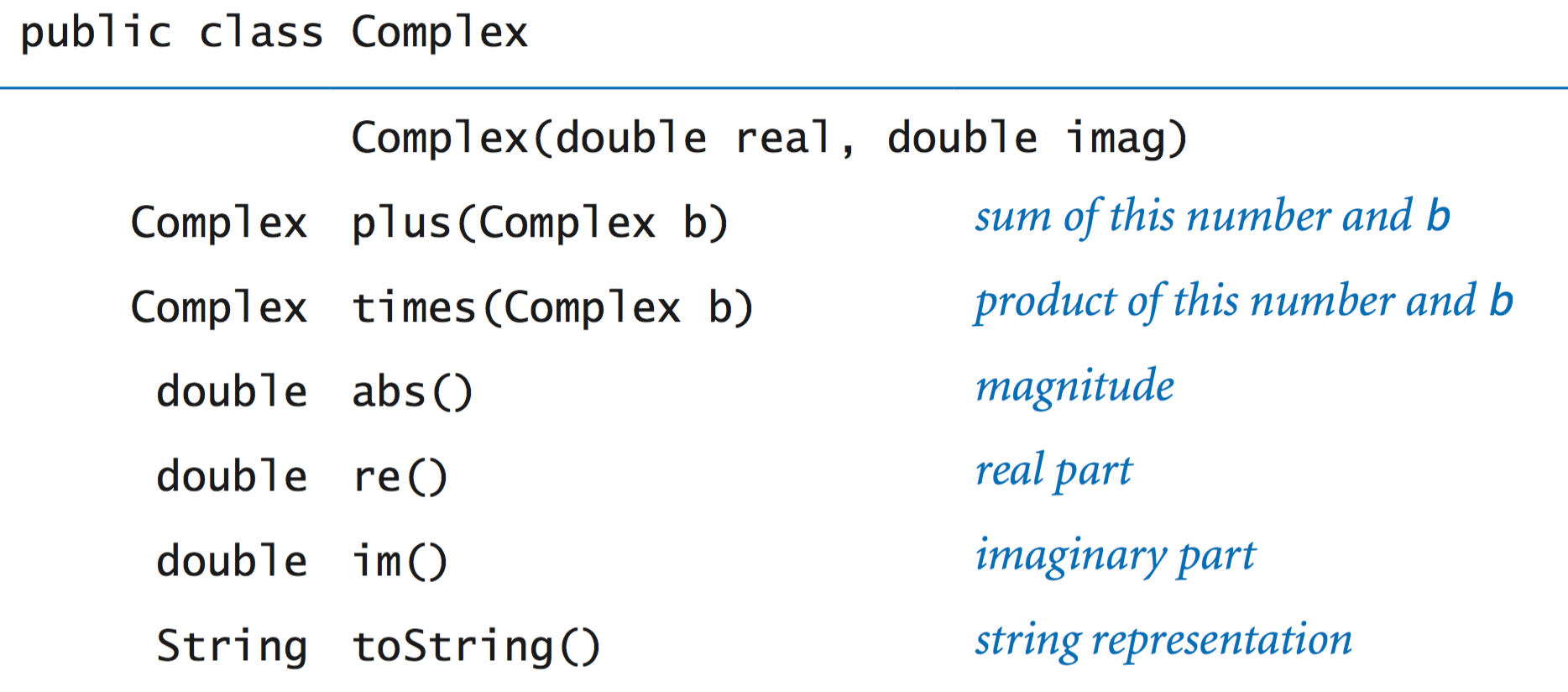

Complex.java is an immutable data type that implements the following API:

This data type introduces a few new features.

Accessing values of other objects of the same type. The instance methods plus() and times() each need to access values in two objects: the object passed as an argument and the object used to invoke the method. If we call the method with a.plus(b), we can access the instance variables of a using the names re and im, as usual. However, to access the instance variables of b, we use the codeb.re and b.im.

Creating and returning new objects. Observe the manner in which plus() and times() provide return values to clients: they need to return a Complex value, so they each compute the requisite real and imaginary parts, use them to create a new object, and then return a reference to that object.

Chaining method calls. Observe the manner in which main() chains two method calls into one compact expressionz.times(z).plus(z0), which corresponds to the mathematical expression z2 + z0.

Final instance variables. The two instance variables in Complex are final, meaning that their values are set for each Complex object when it is created and do not change during the lifetime of that object.

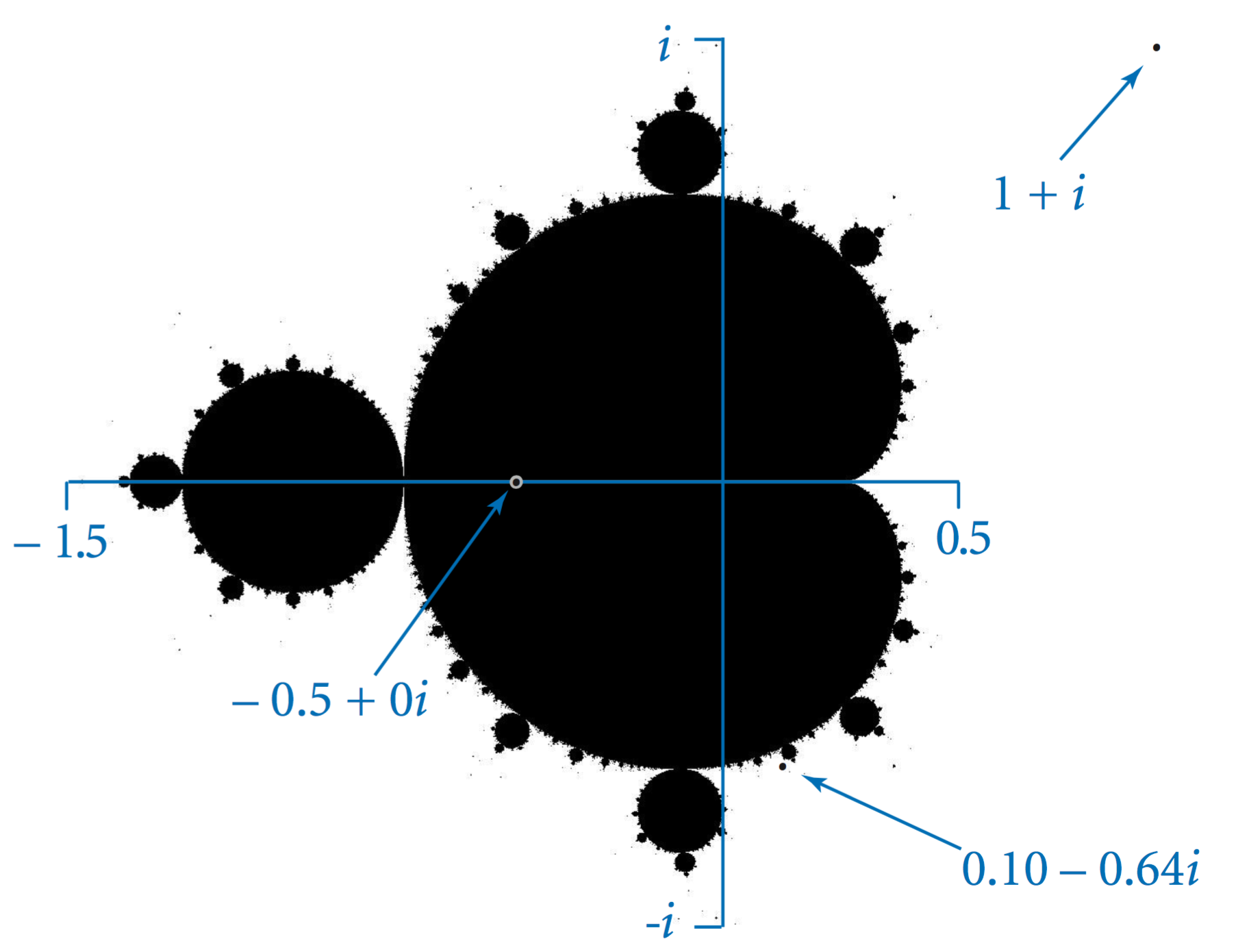

Mandelbrot set.

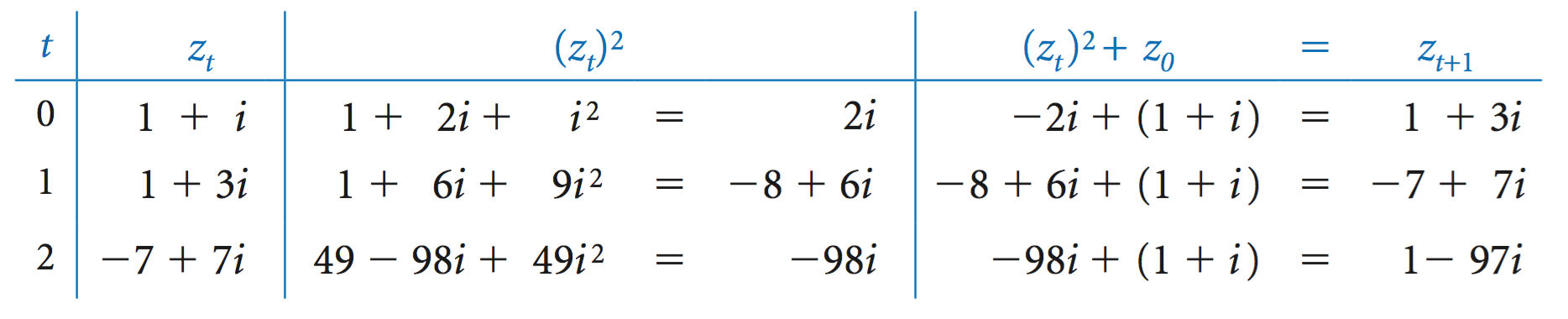

The Mandelbrot set is a specific set of complex numbers with many fascinating properties. The algorithm for determining whether or not a complex number is in the Mandelbrot set is simple: Consider the sequence of complex numbers where. For example, the following table shows the first few entries in the sequence corresponding to :

Now, if the sequence diverges to infinity, then is not in the Mandelbrot set; if the sequence is bounded, then is in the Mandelbrot set. For many points, the test is simple; for many other points, the test requires more computation, as indicated by the examples in the following table:

To visualize the Mandelbrot set, we define an evenly spaced n-by-n pixel grid within a specified square and draw a black pixel if the corresponding point is in the Mandelbrot set and a white pixel if it is not.

But how do we determine whether a complex number is in the Mandelbrot set? For each complex number, Mandelbrot.java computes up to 255 terms in its sequence. If the magnitude ever exceeds 2, then we can conclude that the complex number is not in the set (because it is known that the sequence will surely diverge). Otherwise, we conclude that the complex number is in the set (knowing that our conclusion might be wrong on occasion).

Commercial data processing.

StockAccount.java implements a data type that might be used by a financial institution to keep track of customer information.