Destination: College,U.S.A.

By Yilu Zhao

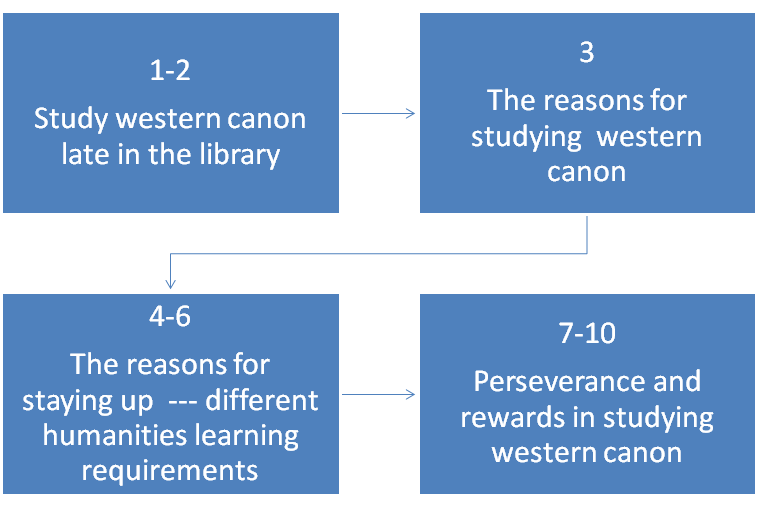

All-Nighters with the Western World

1 In the sleepiness at the end of a library nap, I wasn’t sure where I was. I stretched out my arm to reach for a human being, but what I grabbed was a used copy of The Odyssey, the book about going home.My heart ached.

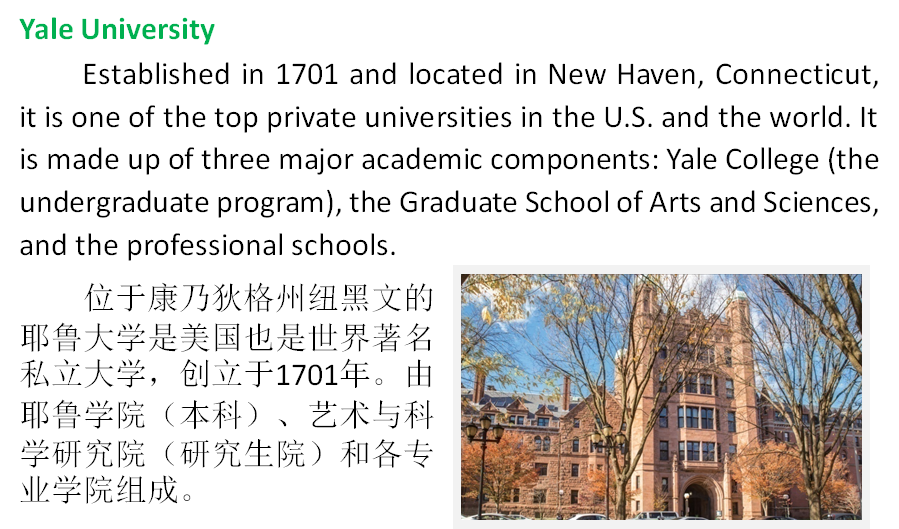

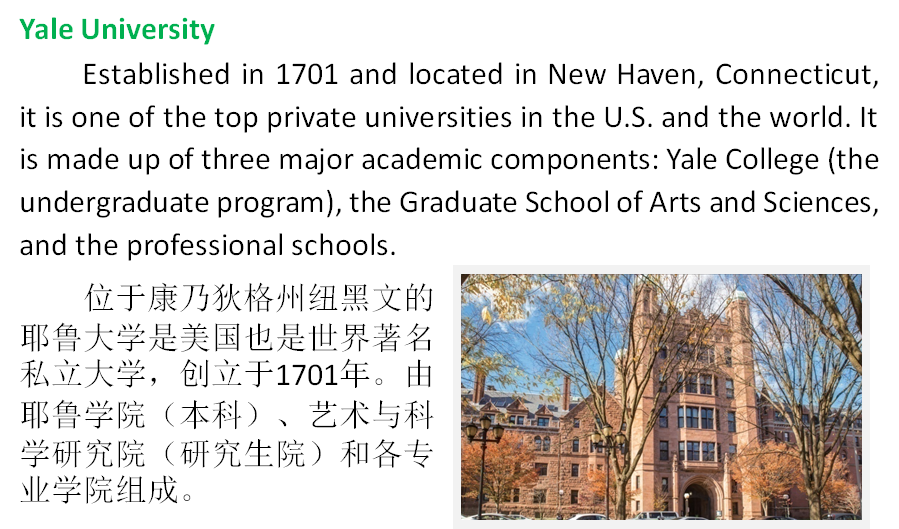

2 It was 2 a.m.The library, flooded with white fluorescent light and smelling of musty books and sweaty sneakers, was eerily quiet. My readings seemed endless. I had been admitted into a three-course, yearlong freshman program called Directed Studies, dubbed Directed Suicide by Yalies. It was supposed to introduce us to“the splendors of Western civilization," in the words of the catalog, by force-feeding the canons of philosophy, literature and history.

3 I wanted very much to study the Western canon, because I knew nothing about it. Yes, McDonald’s ads and Madonna posters were plastered on Shanghai streets, but few Western ideas filtered through. We had been informed of Karl Marx’s habit of sitting at the same spot in the British Library, for instance, but had read none of his original words. Western civilization was different, mysterious and thus alluring. Besides, because I longed to be accepted here, I yearned to understand American society. What better way to comprehend it than to study the very ideas on which it is based?

4 But at 2 a.m., I was tired of them all: Homer, Virgil, Herodotus and Plato. Their words were dull and the presentations difficult to follow. The professors here do not teach in the same way that teachers in China do. Studying humanities in China means memorizing all the “correct,’’ standard interpretations given during lectures. Here, professors ask provocative questions and let the students argue, research and write papers on their own. At Yale, I often waited for theend-of-class “correct" answers, which never came.

5 Learning humanities was secure repetition in China, but it was shaky originality here .And it could be even shakier for me. The name Agamemnon was impossibly long to pronounce, and as a result I didn’t recognize it when we were discussing him in the seminars. I had written my first English essay ever just a year earlier,when applying to colleges, and now came the papers analyzing the canons. And I simply didn’t write in English fast enough to take notes in classes.

6 I hoped my diligence would make up for lack of preparation. On weekend nights, when my American roommates were out on dates, I would tell them I had planned a date with Dante or Aristotle. (They didn’t think it was funny.)

7 On one of those weekend nights, I wrote a paper on Aeneas, the protagonist of The Aeneid, who was destined to found Rome but reluctant to leave behind his native Troy. “Aeneas agonizes,” I wrote.“He hesitates. Natural instincts call him to stick to the past, while at the same time, he feels obligated to obey his father’s instructions for the future.His present life is split, pulled apart by the bygone days and by the days tocome.” I saw myself in what I wrote.

8 During calls home every two weeks, my mother pleaded with me to take chemistry or biology. Science was the same everywhere, she said. And I, like everybody else from China, was well prepared in math, physics and chemistry. (To graduate from astandard six-year Chinese high school, one needs to take five years of physics,four years of chemistry and three years of biology.)

9 Instead, I visited the writing tutor — there is one in every undergraduate residential hall — for every paper I turned in. My papers were always written days before they were due. I lingered after classes to question professors. My classmates lent me their notes so I could learn the skill of note-taking in English.

10 By the time I missed home so much that soup dumplings and sautéed eels popped up in my head as I read, Nietzsche had replaced Plato on the chronological reading list and Flaubert Homer. And every paper of mine came back with an A.