Translate English into Chinese

要求:

1、在通读的基础上,逐段翻译课文;

2、注意专业名词、专有名词的准确性;

3、通过课文学习,了解科技文献的写作特点;

4、学习复杂句子的结构分析。

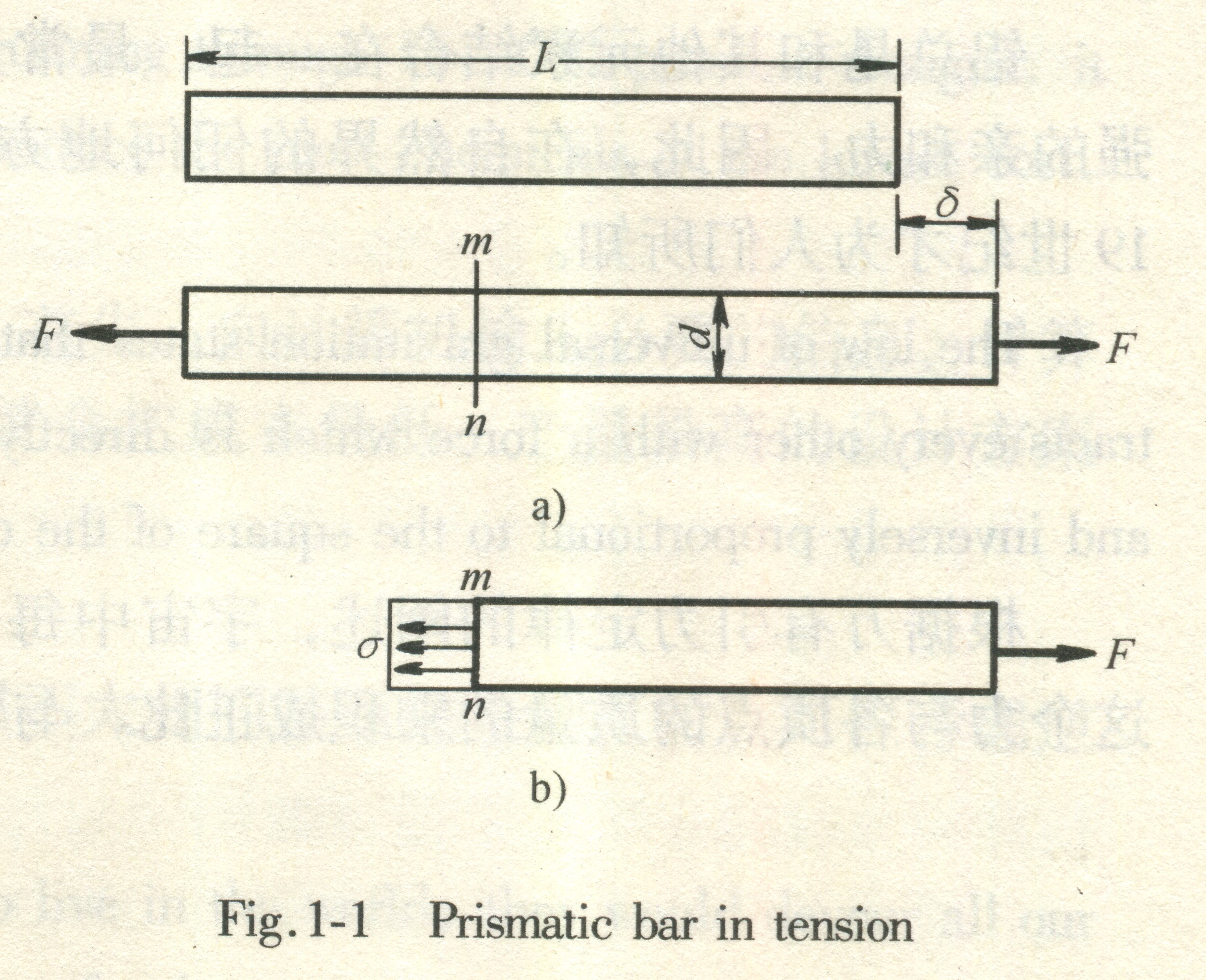

The fundamental concepts of stress and strain can be illustrated by considering a prismatic bar that is loaded by axial forces P at the ends, as shown in Fig. 1-1. A prismatic bar is a straight structural member(构件)having constant cross section throughout its length. In this illustration, the axial forces produce a uniform stretching of the bar, hence, the bar is said to be in tension.

To investigate the internal stresses produced in the bar by the axial forces, we make an imaginary cut at section mn (Fig.1-1a). This section is taken perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the bar; hence, it is known as a cross section. We now isolate the part of the bar to the right of the cut as a free body (Fig. 1-1b). The tensile load P acts at the right-hand end of the free body; at the other end are forces representing the action of the removed part of the bar upon the part that remains.

These forces are continuously distributed over the cross section, analogous to the continuous distribution of hydrostatic pressure over a submerged horizontal surface. The intensity of force (that is, the force per unit area) is called the stress and is commonly denoted by the Greek letter σ(sigma). Assuming that the stress has a uniform distribution over the cross section (see Fig. 1-1b), we can readily see that its resultant is equal to the intensity σtimes the cross-sectional area Aof the bar. Furthermore, from the equilibrium of the body shown in Fig. 1-1b, it is also evident that this resultant must be equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the applied load P. Hence, we obtain

σ =P/A (1-1)

as the equation for the uniform stress in an axially loaded, prismatic bar of arbitrary cross-sectional shape.

When the bar is stretched by the forces P, as shown in the figure, the resulting stresses are tensile stresses; if the forces are reversed in direction, causing the bar to be compressed, we obtain compressive stresses. Inasmuch as the stress σ acts in a direction perpendicular to the cut surface, it is referred to as a normal stress. Thus, normal stresses may be either tensile or compressive stresses.

When a sign convention for normal stresses is required, it is customary to define tensile stresses as positive and compressive stresses as negative.

Because the normal stress σ is obtained by dividing the axial force by thecross-sectional area, it has units of force per unit of area. When SI units are used, force is expressed in newtons (N) and area insquare meters (m2)1. Hence,stress has units of newtons per square meter (N/m2), or pascals (Pa). However, the pascalis such a small unit of stress that it is necessary to work with largemultiples. To illustrate this point, we have only to note that it takes almost7000 pascals to make 1 psi. As an example, atypical tensile stress in a steel bar might have a magnitude of 140 megapascals (140 MPa),which is 140×106pascals.Other units that may be convenient to use are the kilopascal (kPa) and gigapascal (GPa);the former equals 103pascals and the latter equals 109pascals. Although it is not recommended in SI, you willsometimes find stress given in newtons per square millimeter (N/mm2), which is a unitidentical to the megapascal (MPa).

When using USCS units, stress is customarily expressedin pounds per square inch (psi) or kips per square inch (ksi)2. For instance, a typical stress in asteel bar might be 20, 000 psi or 20 ksi.

In order for the equation σ=P/Ato be valid, the stress σ must be uniformly distributed overthe cross section of the bar. This condition is realized if the axial force P acts through the centroid(质心)of the cross sectional area, as demonstrated in Example 1. When the load P does not act at the centroid, bending of the bar will result, anda more complicated analysis is necessary. However, we will assume throughoutthis book that all axial forces are applied at the centroid of the cross section unlessspecifically stated otherwise.

The uniform stress condition picturedin Fig. 1-1b exists throughout the length of the member except near the ends.The stress distribution at the ends of the bar depends upon the details of howthe axial load Pis actually applied. If the load itself is distributed uniformly over the end,then the stress pattern at the end will be the same as elsewhere. However, theload is usually concentrated over a small area, resulting in high localizedstresses and nonuniform stress distributions over crosssections in the vicinity of the load. As we move away from the ends, the stressdistribution gradually approaches the uniform distribution shown in Fig. 1-1b. It is usually safe to assume that the formula σ =P/Amay be used with good accuracy at any point within the bar that is at least adistance d away from the ends, where dis the largest transverse dimension of the bar 3 (see Fig. 1-1a). Of course, even when the stress is notuniform, the equationσ=P/A will give the average normal stress.

An axially loaded bar undergoes a change in length, becoming longer when in tension and shorter when in compression. The total change in length is denoted by the Greek letter δ(delta) and is pictured in Fig. 1-1a for a bar in tension. This elongation is the cumulative result of the stretching of the material throughout the length L of the bar. Let us now assume that the material is the same everywhere in the bar. Then, if we consider half of the bar, it will have an elongation equal to δ/2; similarly, if we consider a unit length of the bar, it will have an elongation equal to 1/L times the total elongation δ. In this manner, we arrive at the concept of elongation per unit length, or strain, denoted by the Greek letter (epsilon) and given by the equation.

Epsilon = δ/L (1-2)

If the bar is in tension, the strain is called a tensile strain, representing an elongation or stretching of the material. If the bar is in compression, the strain is a compressive strain and the bar shortens. Tensile strain is taken as positive, and compressive strain as negative. The strain is called a normal strain because it is associated with normal stresses.

Because normal strain is the ratio of two lengths, it is a dimensionless quantity; that is, it has no units. Thus, strain is expressed as a pure number, independent of any system of units. Numerical values of strain are usually very small, especially for structural materials, which ordinarily undergo only small changes in dimensions. As an example, consider a steel bar having length L of 2.0 m. When loaded in tension, the bar might elongate by an amount δequal to 1.4mm. The corresponding strain is

Epsilon = δ/L =0.0007=700X10-6

In practice, the original units of δand L are sometimes attached to the strain itself, and then the strain is recorded in forms such as mm/m, /m, and in./in. For instance, the strain in the preceding illustration could be given as 700 /m or 700×10-6 in./in.

The definitions of normal stress and strain are based upon purely statical and geometrical considerations, hence Eqs. (1-1) and (1-2) can be used for loads of any magnitude and for any material. The principal requirement is that the deformation of the bar be uniform, which in turn requires that the bar be prismatic, the loads act through the centroids of the cross sections, and the material be homogeneous (that is, the same throughout all parts of the bar)4. The resulting state of stress and strain is called uniaxial stress and strain.