The covid network

Phone data identify travel hubs at risk of a second wave of infections.

Well-networked areas tend to have more infections than their average incomes and population densities suggest

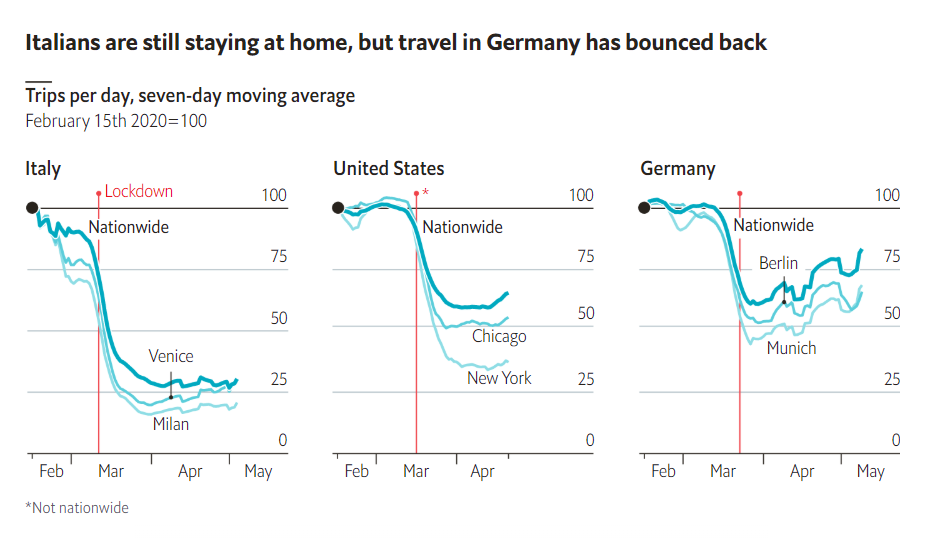

NOW THAT the first wave of covid-19 infections has crested, governments are starting to relax their lockdowns. In Italy shops will open their doors from May 18th. Parts of Germany and America are also reopening on a state-by-state basis. Mobile-phone data show that people are buzzing around a bit more than they did in April.

Greater mobility raises the risk of a second wave of cases. For countries where policies are set locally, a big worry is that outbreaks could begin in areas with lax rules and spread elsewhere. In theory, this risk should mirror “interconnectedness”—the amount of travel to and from each region. One possible explanation for why Lombardy was hit so hard by covid-19 is that it is the best-networked part of Italy.

Teralytics, a Swiss technology firm, has compiled data from Germany, Italy and America that support this hypothesis. Each time a mobile phone leaves one location and arrives at a new one for an hour or more—whether such travel is within a city or for longer distances—Teralytics logs the journey. In the week before lockdowns began, the firm recorded 5.7bn trips. Travel fell by 40% once they were implemented.

To test how interconnectedness affects vulnerability to covid-19, we built two statistical models to predict local infection rates during the period just before lockdowns. The first relied solely on each area’s population density and income. The second added on two measures of propensity for travel: its number of journeys and its “network centrality”, or how many other places it tends to exchange visitors with.

The more elaborate model fared better, with 30% more explanatory power than relying on population density and income alone. Interconnectedness matters a lot. In all three countries, better-networked areas had more infections than the simple model predicted. Less-networked ones had fewer.

Governments should treat travel hubs with caution. So far, many German cities have seen surprisingly few infections—perhaps because the country tests widely, and began locking down earlier in its epidemic (as measured by the death toll) than Italy did. Now that Germany is easing restrictions, its infection rate may rise again. Well-networked Frankfurt is probably at greater risk than, say, comparatively disconnected Hanover, and should reopen relatively slowly. Milan in Italy, and Houston in America, should be cautious, too.

Sources: Teralytics; Eurostat; US Census Bureau; national statistics; The Economist

This article appeared in the Graphic detail section of the print edition under the headline "The covid network"(May 16th 2020)