Chapter 4 Inventory

4.5 Inventory Management

4.5.1 Scope of Inventory Management

Thescope of inventory management concerns the fine lines between replenishmentlead time, carrying costs of inventory, asset management, inventoryforecasting, inventory valuation, inventory visibility, future inventory priceforecasting, physical inventory, available physical space for inventory,quality management, replenishment, returns and defective goods, and demandforecasting. Balancing these competing requirements leads to optimal inventorylevels, which is an ongoing process as the business needs shift and react tothe wider environment.

Inventory management involves a retailerseeking to acquire and maintain a proper merchandise assortment while ordering,shipping, handling, and related costs are kept in check. It also involvessystems and processes that identify inventory requirements, set targets,provide replenishment techniques, report actual and projected inventory statusand handle all functions related to the tracking and management of material.This would include the monitoring of material moved into and out of stockroomlocations and the reconciling of the inventory balances. It also may includeABC analysis, lot tracking, cycle counting support, etc. Management of the inventories,with the primary objective of determining/controlling stock levels within thephysical distribution system, functions to balance the need for productavailability against the need for minimizing stock holding and handling costs. Thus,inventory is a major use of capital and, for this reason, the objectives ofinventory management are to increase corporate profitability, to predict theimpact of corporate policies on inventory levels, and to minimize the totalcost of logistics activities.

Inventory managers must determine how muchinventory to order and when to place the order. In order to illustrate thebasic principles of reorder policy, let’s consider inventory management underconditions of certainty and uncertainty. This latter case is the rule ratherthan the exception.

4.5.2 EOQ Model

Replenishment policy under conditions ofcertainty requires the balancing of ordering costs against inventory carryingcosts. For example, a policy of ordering large quantities infrequently mayresult in inventory carrying costs in excess of the savings in ordering costs.

Orderingcosts for products purchased from an outside supplier typically include a) thecost of transmitting the order, b) the cost of receiving the product, c) thecost of placing it in storage, and d) the cost associated with processing theinvoice for payment.

In thecase of restocking its own field warehouses, the ordering costs of a companytypically include a) the cost of transmitting and processing the inventorytransfer, b) the cost of handling the product if it is in stock, or the cost ofsetting up production to produce it, and the handling cost if the product isnot in stock, c) the cost of receiving at the field location, and d) the costof associated documentation. Remember that only direct out-of-pocket expensesshould be included.

(1) Definition of EOQ

The best ordering policy can be determined byminimizing the total of inventory carrying costs and ordering costs using theeconomic order quantity (EOQ) model.

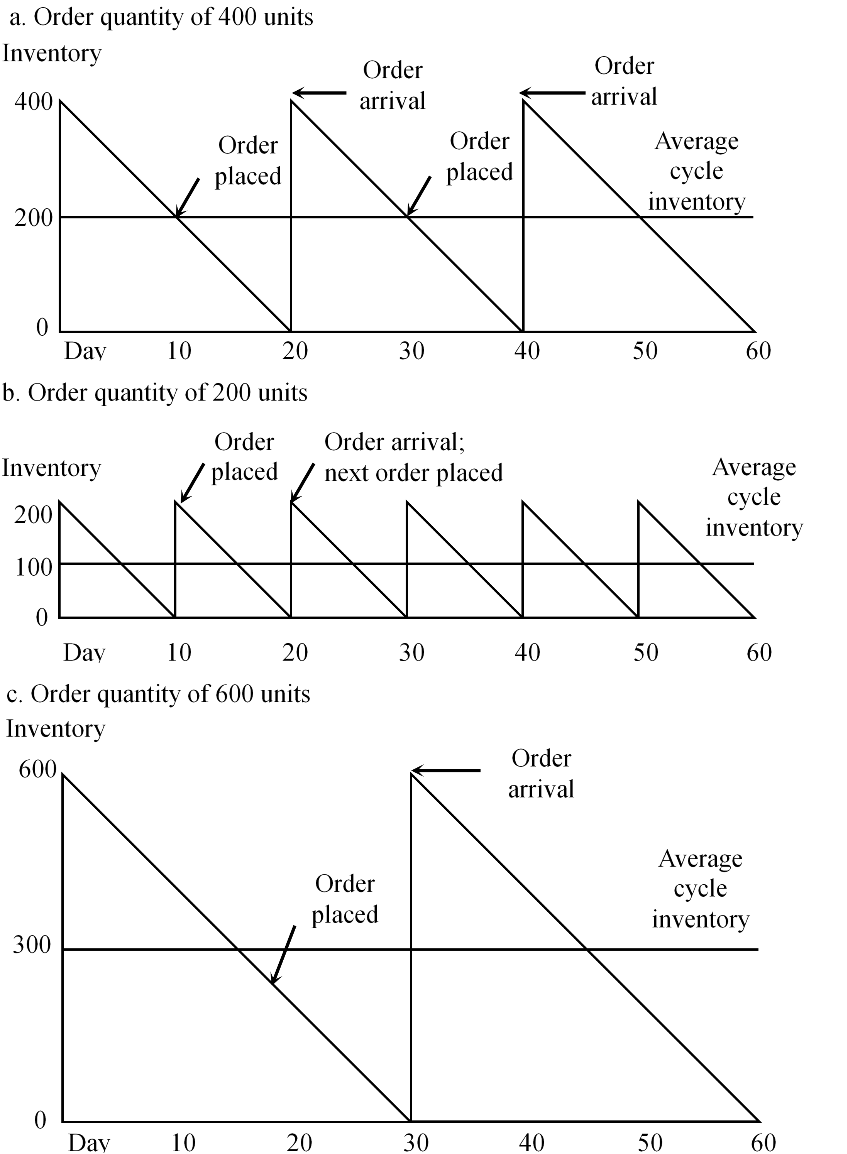

Inreference to the example given in Figure 2.3, two questions seem appropriate:

a)Should we place orders for 200, 400, or 600units, or some other quantity?

b)What is the impact oninventory if orders are placed at 10-, 20-, or30-day intervals, or some othertime period?

Assuming constant demand and lead time, salesof 20 units per day and 240 working days per year, annual sales will be 4,800units. If orders are placed every 10 days, 24 orders of 200 units will beplaced. With a 20-day order interval, 12 orders of 400 units are required. Ifthe 30-day order interval is selected, 8 orders of 600 units are necessary. Theaverage inventory is 100, 200, and 300 units, respectively. Which of thesepolicies would be best?

The cost trade-offs required to determine themost economical order quantity is shown graphically in Figure 4.3.1

Figure 4.5.1 The effect of reorder quantityon average inventory investment with constant demand and lead time

Figure 4.5.2 Cost trade-offs requiredto determine the most economical order quantity

Economic order quantity (EOQ) model is a model that is used to calculate theoptimal quantity that can be purchased or produced to minimize the cost of boththe carrying inventory (Holding Cost) and the processing of purchase orders orproduction set-ups (Ordering Cost). Simply, the Economic Order Quantity (EOQ)is the order quantity that minimizes total holding and ordering costs for theyear.

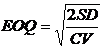

(2)Formula of EOQ

By determining the EOQ and dividingthe annual demand by it, the frequency and size of the order that will minimizethe two costs are identified. The EOQ in units can be calculated usingthe following formula:

![]()

Where

Q* = optimal order quantity per cycle, units;

D = annual demand, units;

S = cost incurred to place a single order, $;

H = holding cost per unit, $.

Q* is derived by minimizing the total annual cost which consists of purchasecost, holding cost and ordering cost.

Since H=C*V, EOQis furtherly expressed in the followingformula:

Where

C= a unitinventory’s purchasing cost, $;

V = carrying costrate of per unit inventory (as a percentage of product cost or value), %.

Underlying assumption of the EOQmodel. The EOQmodel has received significant attention and use in industry; however, it isnot without its limitations. The simple EOQ model is based on certainassumptions. Without these assumptions, the EOQ model cannot work to itsoptimal potential. Following are the underlying assumptions for the EOQ model:

· Thecost of the ordering remains constant.

· Thedemand rate for the year is known and evenly spread throughout the year.

· Thelead time is not fluctuating (lead time is the latency time it takes a processto initiate and complete).

· Nocash or settlement discounts are available, and the purchase price is constantfor every item.

· Theoptimal plan is calculated for only one product.

· Thereis no delay in the replenishment of the stock, and the order is delivered inthe quantity that was demanded, i.e. in whole batch.

These underlying assumptions are the key tothe economic order quantity model, which can help the companies to understandthe shortcomings they are incurring in the application of this model. Even ifall the assumptions don’t hold exactly, the EOQ gives us a good indication ofwhether or not current order quantities are reasonable.

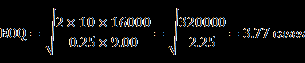

(3) Best ordering policy by EOQ

Now, let us apply the EOQ model todetermine the best ordering policy for the situation described in Figure 2.4: C= $100 per unit, V = 25 percent, S= $40, D = 4,800 units.

![]()

If 20 units fit on a pallet, then the reorderquantity of 120 units would be established. This analysis is shown in tabularform in Table 2.5.

It would be extremely rare to find asituation where demand is constant, lead time is constant, both are known withcertainty, and costs are known precisely. However, the simplifying assumptionsare of great concern only if policy decisions will change as a result of theassumptions made. The EOQ solution is relatively insensitive to smallchanges in the input data. It can be seen from the Figure 2.5 that EOQcurve is relatively flat around the solution point. This is borne out in Table2.5. Although the calculated EOQ was 124 units (rounded to 120), an EOQvariation of 20 units or even 40 units does not significantly change the totalcost.

Table 4.5.3 Cost trade-offs required todetermine the most economic order quantity

| Order Quantity (Units) | Number of Orders (D/Q) | Ordering Cost S ($-) | Holding Cost 1/2´Q´C´V ($-) | Total Cost: ($-) |

| 40 | 120 | 4800 | 500 | 5300 |

| 60 | 80 | 3200 | 750 | 3950 |

| 80 | 60 | 2400 | 1000 | 3400 |

| 100 | 48 | 1920 | 1250 | 3170 |

| 120 | 40 | 1600 | 1500 | 3100 |

| 140 | 35 | 1400 | 1750 | 3150 |

| 160 | 30 | 1200 | 2000 | 3200 |

| 200 | 24 | 960 | 2500 | 3460 |

| 300 | 16 | 640 | 3750 | 4390 |

| 400 | 12 | 480 | 5000 | 5480 |

4.3.3 Adjusted EOQ Model

Typical refinements that must be made to the EOQmodel include adjustments for volume transportation rates and for quantitydiscounts. The simple EOQ model did not consider the impact of these twofactors. The following adjustment can be made to the EOQ formula so thatit will consider the impact of quantity discounts and/or freight breaks:

![]()

Where

Q1= The maximum quantity that can be economically ordered to qualify fora discount on unit cost;

r = The percentage of price reduction if a larger quantity is ordered;

D = The annual demand in units;

C = The inventory carrying cost percentage;

Q0 = The EOQ based on current price.

Using the modified EOQ formula, wewill determine the best ordering policy for the Johnson Manufacturing Company.Johnson Manufacturing produced and sold a complete line of industrialair-conditioning units that were marketed nationally through independentdistributors. The company purchased a line of relays for use in its airconditioners from a manufacturer in the Midwest.It ordered approximately 300 cases of 24 units each, 54 times per year; theannual volume was about 16 000 cases. The purchase price was $8.00 per case,the ordering costs were $10.00 per order, and the inventory carrying cost was25 percent. The relays weighed 25 pounds per case; Johnson Manufacturing paidthe shipping costs. The freight rate was $4.00 per hundredweight (cwt.) onshipments of less than 15 000 pounds, $3.90 per cwt. on shipments of 15 000 to39000 pounds, and $3.64 per cwt. on orders of more than 39 000 pounds. Therelays were shipped on pallets of 20 cases.

First, it is necessary to calculate thetransportation cost for a case of product without discounts for volumeshipments. Shipments of less than 15 000 pounds¾600 cases (15000/25)¾cost$4.00 per cwt., or $1.00 ($4.00/100 lbs. ´ 25 lbs.) per case.

Therefore, without transportation discountsfor shipping in quantities above 15,000 pounds, the delivered cost of a case ofproduct would be $9.00 ($8.00 plus $1.00 transportation), and the EOQwould be:

or 380 cases, rounded to nearest fullpallet.

If the company shipped in quantities of 40000 pounds or more, the cost per case would be $.91 ($3.64/ 100 lbs. ´25 lbs).The percentage price reduction, r, made possible by shipping at thelowest freight cost is:

![]()

The adjusted EOQ is calculated asfollows:

![]()

While the largest freight break only resultsin a 1 percent reduction in the delivered cost of a case of the product, thevolume of annual purchases is large enough that the EOQ changessignificantly, from 380 cases to 1,660 cases.

An alternative to using the above formulawould be to add a column to the analysis shown in Table 4.3.4 and include theannual transportation cost associated with each of the order quantities, addingthis amount to the total costs. The previous example is shown in tabular formin Table 4.3.4, which illustrates that transportation costs have a significantimpact on the purchase decision. The purchase of 380 cases per order wouldrequire 43 orders per year, or the purchase of 16,340 cases in the first year.Therefore, this option is not as attractive as the 400-case order quantity,which would require 40 orders to purchase the necessary 16,000 cases and is$348 less expensive. Ten orders of 1,600 cases yields the lowest total cost.

It is also possible to include purchasediscounts by adding a column, “Annual Product Cost” and appropriately adjustingthe inventory carrying cost and total annual costs columns. Once again, thedesired EOQ would be the order quantity that resulted in the lowesttotal cost.

Table 4.5.4 Costtrade-offs to determine the most economic order quantity with transportationcosts included

| A Possible Order Quantity (Cases) | B Number of Orders per Year | C (A ($-) | D Value of Orders per Year B ($-) | E Transportation Cost per Order ($-) | F Annual Ordering Cost ($-) | G Annual Transportation Cost ($-) | H Inventory Carrying Cost4 ($-) | I Total Annual Cost5 ($-) |

| 300 | 54 | 2400 | 129600 | 3001 | 540 | 16200 | 338 | 17078 |

| 380 | 43 | 3040 | 130720 | 3801 | 430 | 16340 | 428 | 17198 |

| 400 | 40 | 3200 | 128000 | 4001 | 400 | 16000 | 450 | 16850 |

| 800 | 20 | 6400 | 128000 | 7802 | 200 | 15600 | 898 | 16698 |

| 1200 | 14 | 9600 | 134400 | 11702 | 140 | 16380 | 1346 | 17866 |

| 1600 | 10 | 12800 | 128000 | 14563 | 100 | 14560 | 1782 | 164426 |

| 1800 | 9 | 14400 | 129600 | 16383 | 90 | 14742 | 2005 | 16837 |

| 2000 | 8 | 16000 | 128000 | 18203 | 80 | 14560 | 2228 | 16868 |

Note: 1. Orders for less than15,000 lbs, (600 cases) have a rate of $4.00/cwt. which equals $1.00/case.

2. Orders weighing between 15,000lbs. and 39,000 lbs. (600 cases and 1 560 cases) have a rate of $3.90/cwt.which equals 97.5c/case.

3. Orders weighing 40,000 lbs, ormore (1,600 cases) have a rate of $3.64/cwt. which equals 91 c/case.

4. Inventory carrying cost = 1/2 (C+ E) (25%).

5. I=F+G+H.

6. Lowest total cost.

4.3.3 Calculating Safety StockRequirements

(1) Inventory management under uncertainty

As we have noted, EOQ ordering policy issuitable for the inventory management under certainty conditions. But ifmanagers rarely, if ever, know for sure what demand to expect for the firm’sproducts. Many factors including economic conditions, competitive actions,changes in government regulations, market shifts, and changes in consumerbuying patterns may influence forecast accuracy. Order cycle times are also notconstant. Transit times vary, it may take more time to assemble an order orwait for scheduled production on one occasion than another, supplier lead timesfor components and raw materials may not be consistent, and suppliers may nothave the capability of responding to changes in demand.

Consequently, management has the option ofeither maintaining additional inventory in the form of safety stocks or riskinga potential loss of sales revenue due to stockouts at a distribution center. Wemust thus consider an additional cost trade-off: inventory carrying costsversus stockout costs.

The uncertainties associated with demand andlead time cause most managers to concentrate on when to order rather than onthe order quantity. The order quantity is important to the extent that itinfluences the number of orders, and consequently the number of times that thecompany is exposed to a potential stockout at the end of each order cycle. Thepoint at which the order is placed is the primary determinant of the futureability to fill demand while waiting for replenishment stock.

One method used for inventory control underconditions of uncertainty is the fixed order point, fixed order quantity model.With this method, an order is placed when the inventory on hand and on orderreaches a predetermined minimum level required to satisfy demand during theorder cycle. The economic order quantity will be ordered whenever demand dropsthe inventory level to the reorder point.

In contrast, a fixed order interval modelcompares current inventory with forecast demand, and places an order for thenecessary quantity at a regular, specified time. In other words, the intervalbetween orders is fixed. This method facilitates combining orders for variousitems in a vendor’s line, thereby qualifying for volume purchase discounts andfreight consolidation savings.

(2) Safety stock calculation

The amount of safety stock necessary tosatisfy a given level of demand can be determined by computer simulation orstatistical techniques. In this illustration we will address the use ofstatistical techniques. In calculating safety stock levels it is necessary toconsider the joint impact of demand and replenishment cycle variability. Thiscan be accomplished by gathering statistically valid samples of data on recentsales volumes and replenishment cycles. Once the data are gathered it is possibleto determine safety stock requirements by using this formula:

![]()

Where

![]() = Units of safety stock needed to satisfy 68 percent of allprobabilities (one standard deviation);

= Units of safety stock needed to satisfy 68 percent of allprobabilities (one standard deviation);

![]() = Average replenishment cycle;

= Average replenishment cycle;

![]() = Standard deviation of the replenishment cycle;

= Standard deviation of the replenishment cycle;

![]() = Average daily sales;

= Average daily sales;

![]() = Standard deviation of daily sales.

= Standard deviation of daily sales.

Assume that the sales history contained inTable 4.3.5 has been developed for market area 1. The next step is to calculatethe standard deviation of daily sales as shown in Table 2.8.

Table 4.5.5 Sales history for market area 1

| Day | Sales in Cases | Day | Sales in Cases |

| 1 | 100 | 14 | 80 |

| 2 | 80 | 15 | 90 |

| 3 | 70 | 16 | 90 |

| 4 | 60 | 17 | 100 |

| 5 | 80 | 18 | 140 |

| 6 | 90 | 19 | 110 |

| 7 | 120 | 20 | 120 |

| 8 | 110 | 21 | 70 |

| 9 | 100 | 22 | 100 |

| 10 | 110 | 23 | 130 |

| 11 | 130 | 24 | 110 |

| 12 | 120 | 25 | 90 |

| 13 | 100 |

Table 4.5.6 Calculation of standard deviation of sales

| Daily Sales in Cases | Frequency(f) | Deviation from Mean (d) | Deviation Squared (d2) | fd2 |

| 60 | 1 | -40 | 1 600 | 1 600 |

| 70 | 2 | -30 | 900 | 1 800 |

| 80 | 3 | -20 | 400 | 1 200 |

| 90 | 4 | -10 | 100 | 400 |

| 100 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 110 | 4 | +10 | 100 | 400 |

| 120 | 3 | +20 | 400 | 1 200 |

| 130 | 2 | +30 | 900 | 1 800 |

| 140 | 1 | +40 | 1 600 | 1 600 |

|

=100 | n=25 | å fd2=10 000 |

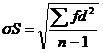

From this sample we cancalculate the standard deviation of sales. The formula is:

Where

sS= Standard deviation of daily sales;

f = Frequency of event;

d=Deviation of event from mean;

n=Total observation.