·ideas

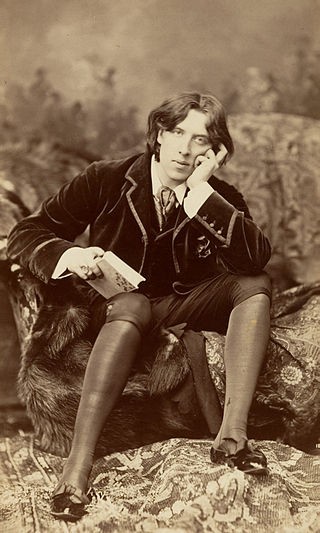

Apprenticeship of an aesthete: 1880s

He had been publishinglyrics and poems in magazines since his entering Trinity College, especially inKottabos and the Dublin University Magazine. In mid-1881, at 27 years old,Poems collected, revised and expanded his poetic efforts. The book wasgenerally well received, and sold out its first print run of 750 copies,prompting further printings in 1882. It was bound in rich, enamel, parchmentcover (embossed with gilt blossom) and printed on hand-made Dutch paper; Wildepresented many copies to the dignitaries and writers who received him over thenext few years. The Oxford Union condemned the book for alleged plagiarism in atight vote. The librarian, who had requested the book for the library, returnedthe presentation copy to Wilde with a note of apology. Richard Ellmann arguesthat Wilde's poem "Hélas!" was a sincere, though flamboyant, attemptto explain the dichotomies he saw in himself:

He had been publishinglyrics and poems in magazines since his entering Trinity College, especially inKottabos and the Dublin University Magazine. In mid-1881, at 27 years old,Poems collected, revised and expanded his poetic efforts. The book wasgenerally well received, and sold out its first print run of 750 copies,prompting further printings in 1882. It was bound in rich, enamel, parchmentcover (embossed with gilt blossom) and printed on hand-made Dutch paper; Wildepresented many copies to the dignitaries and writers who received him over thenext few years. The Oxford Union condemned the book for alleged plagiarism in atight vote. The librarian, who had requested the book for the library, returnedthe presentation copy to Wilde with a note of apology. Richard Ellmann arguesthat Wilde's poem "Hélas!" was a sincere, though flamboyant, attemptto explain the dichotomies he saw in himself:

Todrift with every passion till my soul

Isa stringed lute on which all winds can play

Punchwas less enthusiastic; "The poet is Wilde, but his poetry's tame" wastheir verdict.

Shorter fictions

Laid published The HappyPrince and Other Tales in 1888, and had been regularly writing fairy storiesfor magazines. In 1891 he published two more collections, Lord Arthur Savile'sCrime and Other Stories, and in September A House of Pomegranates was dedicated"To Constance Mary Wilde". "The Portrait of Mr. W. H.",which Wilde had begun in 1887, was first published in Blackwood's EdinburghMagazine in July 1889. It is a short story, which reports a conversation, inwhich the theory that Shakespeare's sonnets were written out of the poet's loveof the boy actor "Willie  Hughes", is advanced, retracted, and thenpropounded again. The only evidence for this is two supposed puns within thesonnets themselves. The anonymous narrator is at first sceptical, then believing,finally flirtatious with the reader: he concludes that "there is really agreat deal to be said of the Willie Hughes theory of Shakespeare'ssonnets." By the end fact and fiction have melded together. Arthur Ransomewrote that Wilde "read something of himself into Shakespeare'ssonnets" and became fascinated with the "Willie Hughes theory"despite the lack of biographical evidence for the historical William Hughes'existence. Instead of writing a short but serious essay on the question, Wildetossed the theory amongst the three characters of the story, allowing it tounfold as background to the plot. The story thus is an early masterpiece ofWilde's combing many elements that interested him, conversation, literature andthe idea that to shed oneself of an idea one must first convince another of itstruth. Ransome concludes that Wilde succeeds precisely because the literarycriticism is unveiled with such a deft touch. Though containing nothing but"special pleading", it would not, he says "be possible to buildan airier castle in Spain than this of the imaginary William Hughes" wecontinue listening nonetheless to be charmed by the telling. "You mustbelieve in Willie Hughes," Wilde told an acquaintance, "I almost domyself."

Hughes", is advanced, retracted, and thenpropounded again. The only evidence for this is two supposed puns within thesonnets themselves. The anonymous narrator is at first sceptical, then believing,finally flirtatious with the reader: he concludes that "there is really agreat deal to be said of the Willie Hughes theory of Shakespeare'ssonnets." By the end fact and fiction have melded together. Arthur Ransomewrote that Wilde "read something of himself into Shakespeare'ssonnets" and became fascinated with the "Willie Hughes theory"despite the lack of biographical evidence for the historical William Hughes'existence. Instead of writing a short but serious essay on the question, Wildetossed the theory amongst the three characters of the story, allowing it tounfold as background to the plot. The story thus is an early masterpiece ofWilde's combing many elements that interested him, conversation, literature andthe idea that to shed oneself of an idea one must first convince another of itstruth. Ransome concludes that Wilde succeeds precisely because the literarycriticism is unveiled with such a deft touch. Though containing nothing but"special pleading", it would not, he says "be possible to buildan airier castle in Spain than this of the imaginary William Hughes" wecontinue listening nonetheless to be charmed by the telling. "You mustbelieve in Willie Hughes," Wilde told an acquaintance, "I almost domyself."

Essays and dialogues

Wilde, having tired ofjournalism, had been busy setting out his aesthetic ideas more fully in aseries of longer prose pieces which were published in the majorliterary-intellectual journals of the day. In January 1889, The Decay of Lying:A Dialogue appeared in The Nineteenth Century, and Pen, Pencil and Poison, asatirical biography of Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, in the Fortnightly Review,edited by Wilde's friend Frank Harris.[76] Two of Wilde's four writings onaesthetics are dialogues: though Wilde had evolved professionally from lecturerto writer, he retained an oral tradition of sorts. Having always excelled as awit and raconteur, he often composed by assembling phrases, bons mots andwitticisms into a longer, cohesive work.

The Picture ofDorian Gray

The first version of ThePicture of Dorian Gray was published as the lead story in the July 1890 editionof Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, along with five others. The story begins witha man painting a picture of Gray. When Gray, who has a "face like ivory androse leaves", sees his finished portrait, he breaks down. Distraught thathis beauty will fade while the portrait stays beautiful, he inadvertently makesa Faustian bargain in which only the painted image grows old while he staysbeautiful and young. For Wilde, the purpose of art would be to guide life as ifbeauty alone were its object. As Gray's portrait allows him to escape thecorporeal ravages of his hedonism, Wilde sought to juxtapose the beauty he sawin art with daily life.

The first version of ThePicture of Dorian Gray was published as the lead story in the July 1890 editionof Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, along with five others. The story begins witha man painting a picture of Gray. When Gray, who has a "face like ivory androse leaves", sees his finished portrait, he breaks down. Distraught thathis beauty will fade while the portrait stays beautiful, he inadvertently makesa Faustian bargain in which only the painted image grows old while he staysbeautiful and young. For Wilde, the purpose of art would be to guide life as ifbeauty alone were its object. As Gray's portrait allows him to escape thecorporeal ravages of his hedonism, Wilde sought to juxtapose the beauty he sawin art with daily life.

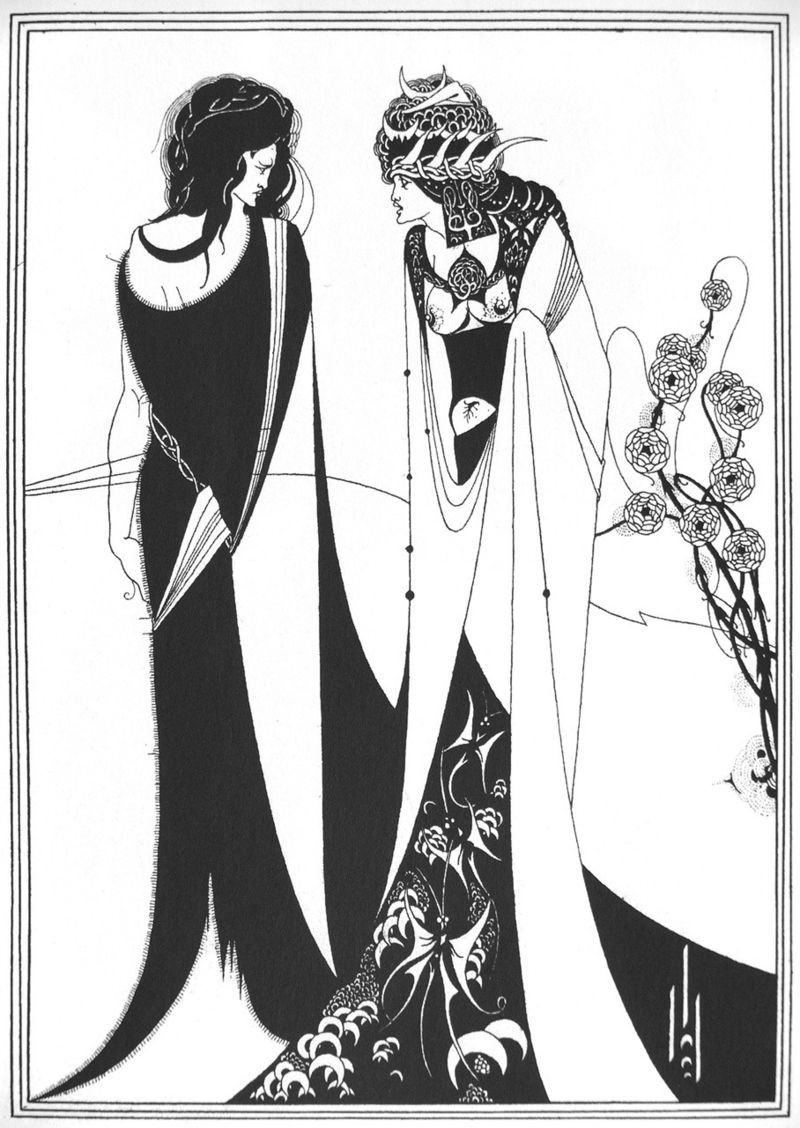

Salomé

The 1891 census records theWildes' residence at 16 Tite Street, where he lived with his wife Constance andtwo sons. Wilde though, not content with being better known than ever inLondon, returned to Paris in October 1891, this time as a respected writer. Hewas received at the salons littéraires, including the famous mardis of StéphaneMallarmé, a renowned symbolist poet of the time. Wilde's two plays during the1880s, Vera; or, The Nihilists and The Duchess of Padua, had not met with muchsuccess. He had continued his interest in the theatre and now, after findinghis voice in prose, his thoughts turned again to the dramatic form as thebiblical iconography of Salome filled his mind. One evening, after discussingdepictions of Salome throughout history, he returned to his hotel and noticed ablank copybook lying on the desk, and it occurred to him to write in it what hehad been saying. The result was a new play, Salomé, written rapidly and inFrench.

A tragedy, it tells thestory of Salome, the stepdaughter of the tetrarch Herod Antipas, who, to herstepfather's dismay but mother's delight, requests the head of Jokanaan (Johnthe Baptist) on a silver platter as a reward for dancing the Dance of the SevenVeils. When Wilde returned to London just before Christmas the Paris Echoreferred to him as "le great event" of the season. Rehearsals of theplay, starring Sarah Bernhardt, began but the play was refused a licence by theLord Chamberlain, since it depicted biblical characters. Salome was publishedjointly in Paris and London in 1893, but was not performed until 1896 in Paris,during Wilde's later incarceration.

Comedies of society

Wilde, who had first set outto irritate Victorian society with his dress and talking points, then outrageit with Dorian Gray, his novel of vice hidden beneath art, finally found a wayto critique society on its own terms. Lady Windermere's Fan was first performedon 20 February 1892 at St James Theatre, packed with the cream of society. Onthe surface a witty comedy, there is subtle subversion underneath: "itconcludes with collusive concealment rather than collective disclosure".The audiences, like Lady Windermere, are forced to soften harsh social codes infavour of a more nuanced view. The play was enormously popular, touring thecountry for months, but largely trashed by conservative critics. It wasfollowed by A Woman of No Importance in 1893, another Victorian comedy:revolving around the spectre of illegitimate births, mistaken identities andlate revelations. Wilde was commissioned to write two more plays and An IdealHusband, written in 1894, followed in January 1895.

Wilde, who had first set outto irritate Victorian society with his dress and talking points, then outrageit with Dorian Gray, his novel of vice hidden beneath art, finally found a wayto critique society on its own terms. Lady Windermere's Fan was first performedon 20 February 1892 at St James Theatre, packed with the cream of society. Onthe surface a witty comedy, there is subtle subversion underneath: "itconcludes with collusive concealment rather than collective disclosure".The audiences, like Lady Windermere, are forced to soften harsh social codes infavour of a more nuanced view. The play was enormously popular, touring thecountry for months, but largely trashed by conservative critics. It wasfollowed by A Woman of No Importance in 1893, another Victorian comedy:revolving around the spectre of illegitimate births, mistaken identities andlate revelations. Wilde was commissioned to write two more plays and An IdealHusband, written in 1894, followed in January 1895.

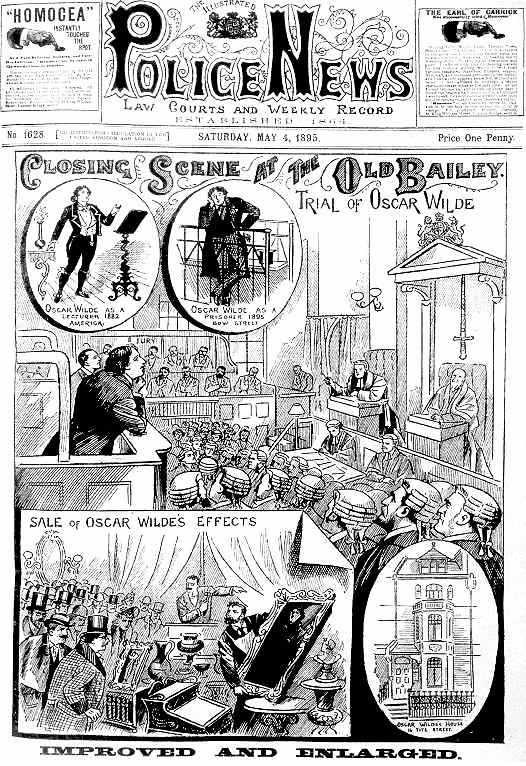

Queensberryfamily

In mid-1891 Lionel Johnsonintroduced Wilde to Lord Alfred Douglas, an undergraduate at Oxford at thetime. Known to his family and friends as "Bosie", he was a handsomeand spoilt young man. An intimate friendship sprang up between Wilde andDouglas and by 1893 Wilde was infatuated with Douglas and they consortedtogether regularly in a tempestuous affair. If Wilde was relatively indiscreet,even flamboyant, in the way he acted, Douglas was reckless in public. Wilde,who was earning up to £100 a week from his plays (his salary at The Woman'sWorld had been £6), indulged Douglas's every whim: material, artistic orsexual.

The Importance of Being Earnest

Wilde's final play againreturns to the theme of switched identities: the play's two protagonists engagein "bun burying" (the maintenance of alternative personas in the townand country) which allows them to escape Victorian social mores. Earnest iseven lighter in tone than Wilde's earlier comedies. While their charactersoften rise to serious themes in moments of crisis, Earnest lacks the by-nowstock Wildean characters: there is no "woman with a past", theprincipals are neither villainous nor cunning, simply idle cultivés, and theidealistic young women are not that innocent. Mostly set in drawing rooms andalmost completely lacking in action or violence, Earnest lacks theself-conscious decadence found in The Picture of Dorian Gray and Salome.

Wilde's final play againreturns to the theme of switched identities: the play's two protagonists engagein "bun burying" (the maintenance of alternative personas in the townand country) which allows them to escape Victorian social mores. Earnest iseven lighter in tone than Wilde's earlier comedies. While their charactersoften rise to serious themes in moments of crisis, Earnest lacks the by-nowstock Wildean characters: there is no "woman with a past", theprincipals are neither villainous nor cunning, simply idle cultivés, and theidealistic young women are not that innocent. Mostly set in drawing rooms andalmost completely lacking in action or violence, Earnest lacks theself-conscious decadence found in The Picture of Dorian Gray and Salome.