·ideas

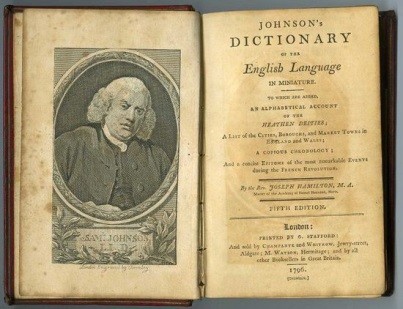

A Dictionary of the English Language

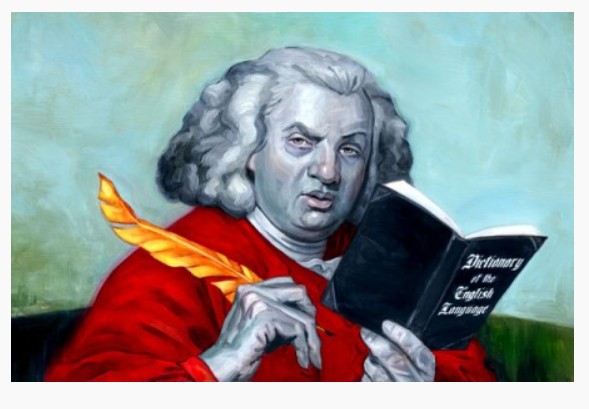

In 1746, a group ofpublishers approached Johnson with an idea about creating an authoritativedictionary of the English language. A contract with William Strahan andassociates, worth 1,500 guineas, was signed on the morning of 18 June 1746.Johnson claimed that he could finish the project in three years. In comparison,the Académie Française had forty scholars spending forty years to completetheir dictionary, which prompted Johnson to claim, "This is theproportion. Let me see; forty times forty is sixteen hundred. As three tosixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman."Although he did not succeed in completing the work in three years, he did manageto finish it in nine. Some criticized the dictionary, including ThomasBabington Macaulay, who described Johnson as "a wretchedetymologist," but according to Bate, the Dictionary "easily ranks asone of the greatest single achievements of scholarship, and probably thegreatest ever performed by one individual who laboured under anything like thedisadvantages in a comparable length of time."

Johnson's dictionary was notthe first, nor was it unique. It was, however, the most commonly used andimitated for the 150 years between its first publication and the completion ofthe Oxford English Dictionary in 1928. Other dictionaries, such as Nathan Bailey'sDictionarium Britannicum, included more words, and in the 150 years precedingJohnson's dictionary about twenty other general-purpose monolingual"English" dictionaries had been produced.

For a decade, Johnson'sconstant work on the Dictionary disrupted his and Tetty's living conditions. Hehad to employ a number of assistants for the copying and mechanical work, whichfilled the house with incessant noise and clutter. In preparation, Johnsonwrote a Plan for the Dictionary. Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, wasthe patron of the Plan, to Johnson's displeasure.

The Dictionary was finallypublished in April 1755, with the title page acknowledging that Oxford hadawarded Johnson a Master of Arts degree in anticipation of the work. The dictionaryas published was a huge book.

Essays

In 1750, he decided toproduce a series of essays under the title The Rambler that were to bepublished every Tuesday and Saturday and sell for two pence each. Explainingthe title years later, he told his friend, the painter Joshua Reynolds: "Iwas at a loss how to name it. I sat down at night upon my bedside, and

resolvedthat I would not go to sleep till I had fixed its title. The Rambler seemed thebest that occurred, and I took it." These essays, often on moral andreligious topics, tended to be graver than the title of the series wouldsuggest; his first comments in The Rambler were to ask "that in thisundertaking thy Holy Spirit may not be withheld from me, but that I may promotethy glory, and the salvation of myself and others." The popularity of TheRambler took off once the issues were collected in a volume; they werereprinted nine times during Johnson's life.

Poetry

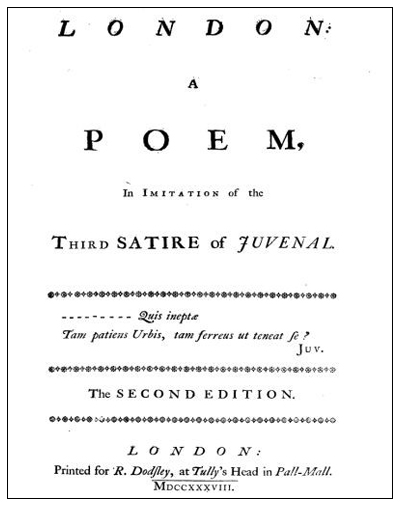

However, not all of his workwas confined to The Rambler. His most highly regarded poem,  The Vanity of HumanWishes, was written with such "extraordinary speed" that Boswellclaimed Johnson "might have been perpetually a poet". The poem is animitation of Juvenal's Satire X and claims that "the antidote to vain humanwishes is non-vain spiritual wishes". In particular, Johnson emphasises"the helpless vulnerability of the individual before the socialcontext" and the "inevitable self-deception by which human beings areled astray". The poem was critically celebrated but it failed to becomepopular, and sold fewer copies than London. In 1749, Garrick made good on hispromise that he would produce Irene, but its title was altered to Mahomet andIrene to make it "fit for the stage." The show eventually ran fornine nights.

The Vanity of HumanWishes, was written with such "extraordinary speed" that Boswellclaimed Johnson "might have been perpetually a poet". The poem is animitation of Juvenal's Satire X and claims that "the antidote to vain humanwishes is non-vain spiritual wishes". In particular, Johnson emphasises"the helpless vulnerability of the individual before the socialcontext" and the "inevitable self-deception by which human beings areled astray". The poem was critically celebrated but it failed to becomepopular, and sold fewer copies than London. In 1749, Garrick made good on hispromise that he would produce Irene, but its title was altered to Mahomet andIrene to make it "fit for the stage." The show eventually ran fornine nights.

Literary criticism

Johnson's works, especiallyhis Lives of the Poets series, describe various features of excellent writing.He believed that the best poetry relied on contemporary language, and hedisliked the use of decorative or purposefully archaic language. He wassuspicious of the poetic language used by Milton, whose blank verse he believedwould inspire many bad imitations. Also, Johnson opposed the poetic language ofhis contemporary Thomas Gray. His greatest complaint was that obscure allusionsfound in works like Milton's Lycidas were overused; he preferred poetry thatcould be easily read and understood. In addition to his views on language,Johnson believed that a good poem incorporated new and unique imagery.

In his smaller poetic works,Johnson relied on short lines and filled his work with a feeling of empathy,which possibly influenced Housman's poetic style. In London, his firstimitation of Juvenal, Johnson uses the poetic form to express his politicalopinion and, as befits a young writer, approaches the topic in a playful andalmost joyous manner. However, his second imitation, The Vanity of HumanWishes, is completely different; the language remains simple, but the poem ismore complicated and difficult to read because Johnson is trying to describecomplex Christian ethics. These Christian values are not unique to the poem,but contain views expressed in most of Johnson's works. In particular, Johnson emphasizesGod's infinite love and shows that happiness can be attained through virtuousaction.

When it came to biography,Johnson disagreed with Plutarch's use of biography to praise and to teachmorality. Instead, Johnson believed in portraying the biographical subjectsaccurately and including any negative aspects of their lives. Because hisinsistence on accuracy in biography was little short of revolutionary, Johnsonhad to struggle against a society that was unwilling to accept biographicaldetails that could be viewed as tarnishing a reputation; this became thesubject of Rambler 60. Furthermore, Johnson believed that biography should notbe limited to the most famous and that the lives of lesser individuals, too,were significant; thus in his Lives of the Poets he chose both great and lesserpoets. In all his biographies he insisted on including what others would haveconsidered trivial details to fully describe the lives of his subjects. Johnsonconsidered the genre of autobiography and diaries, including his own, as onehaving the most significance; in Idler 84 he explains how a writer of anautobiography would be the least likely to distort his own life.

When it came to biography,Johnson disagreed with Plutarch's use of biography to praise and to teachmorality. Instead, Johnson believed in portraying the biographical subjectsaccurately and including any negative aspects of their lives. Because hisinsistence on accuracy in biography was little short of revolutionary, Johnsonhad to struggle against a society that was unwilling to accept biographicaldetails that could be viewed as tarnishing a reputation; this became thesubject of Rambler 60. Furthermore, Johnson believed that biography should notbe limited to the most famous and that the lives of lesser individuals, too,were significant; thus in his Lives of the Poets he chose both great and lesserpoets. In all his biographies he insisted on including what others would haveconsidered trivial details to fully describe the lives of his subjects. Johnsonconsidered the genre of autobiography and diaries, including his own, as onehaving the most significance; in Idler 84 he explains how a writer of anautobiography would be the least likely to distort his own life.

Johnson's thoughts onbiography and on poetry coalesced in his understanding of what would make agood critic. His works were dominated with his intent to use them for literarycriticism. This was especially true of his Dictionary of which he wrote:"I lately published a Dictionary like those compiled by the academies ofItaly and France, for the use of such as aspires to exactness of criticism orelegance of style". Although a smaller edition of his Dictionary becamethe standard household dictionary, Johnson's original Dictionary was anacademic tool that examined how words were used, especially in literary works.To achieve this purpose, Johnson included quotations from Bacon, Hooker,Milton, Shakespeare, Spenser, and many others from what he considered to be themost important literary fields: natural science, philosophy, poetry, andtheology. These quotations and usages were all compared and carefully studiedin the Dictionary so that a reader could understand what words in literaryworks meant in context.

Johnson did not attempt to create schools of theories to analysethe aesthetics of literature. Instead, he used his criticism for the practicalpurpose of helping others to better read and understand literature. When itcame to Shakespeare's plays, Johnson emphasized the role of the reader inunderstanding language: "If Shakespeare has difficulties above otherwriters, it is to be imputed to the nature of his work, which required the useof common colloquial language, and consequently admitted many phrases allusive,elliptical, and proverbial, such as we speak and hear every hour withoutobserving them".

His works on Shakespeare weredevoted not merely to Shakespeare, but to understanding literature as a whole;in his Preface to Shakespeare, Johnson rejects the previous dogma of theclassical unities and argues that drama should be faithful to life. However,Johnson did not only defend Shakespeare; he discussed Shakespeare's faults,including his lack of morality, his vulgarity, his carelessness in craftingplots, and his occasional inattentiveness when choosing words or word order. Aswell as direct literary criticism, Johnson emphasised the need to establish atext that accurately reflects what an author wrote. Shakespeare's plays, inparticular, had multiple editions, each of which contained errors caused by theprinting process. This problem was compounded by careless editors who deemeddifficult words incorrect, and changed them in later editions. Johnson believedthat an editor should not alter the text in such a way.