·philosophy

Recurrentthemes

Plato often discusses the father-sonrelationship and the question of whether a father's interest in his sons hasmuch to do with how well his sons turn out. In ancient Athens, a boy wassocially located by his family identity, and Plato often refers to hischaracters in terms of their paternal and fraternal relationships. Socrates wasnot a family man, and saw himself as the son of his mother, who was apparentlya midwife. A divine fatalist, Socrates mocks men who spent exorbitant fees on tutorsand trainers for their sons, and repeatedly ventures the idea that goodcharacter is a gift from the gods. Crito reminds Socrates that orphans are atthe mercy of chance, but Socrates is unconcerned. In the Theaetetus, he isfound recruiting as a disciple a young man whose inheritance has beensquandered. Socrates twice compares the relationship of the older man and hisboy lover to the father-son relationship (Lysis 213a, Republic 3.403b), and inthe Phaedo, Socrates' disciples, towards whom he displays more concern than hisbiological sons, say they will feel "fatherless" when he is gone.

Plato often discusses the father-sonrelationship and the question of whether a father's interest in his sons hasmuch to do with how well his sons turn out. In ancient Athens, a boy wassocially located by his family identity, and Plato often refers to hischaracters in terms of their paternal and fraternal relationships. Socrates wasnot a family man, and saw himself as the son of his mother, who was apparentlya midwife. A divine fatalist, Socrates mocks men who spent exorbitant fees on tutorsand trainers for their sons, and repeatedly ventures the idea that goodcharacter is a gift from the gods. Crito reminds Socrates that orphans are atthe mercy of chance, but Socrates is unconcerned. In the Theaetetus, he isfound recruiting as a disciple a young man whose inheritance has beensquandered. Socrates twice compares the relationship of the older man and hisboy lover to the father-son relationship (Lysis 213a, Republic 3.403b), and inthe Phaedo, Socrates' disciples, towards whom he displays more concern than hisbiological sons, say they will feel "fatherless" when he is gone.

Severaldialogues tackle questions about art: Socrates says that poetry is inspired bythe muses, and is not rational. He speaks approvingly of this, and other formsof divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreaming) in the Phaedrus(265a–c), and yet in the Republic wants to outlaw Homer's great poetry andlaughter as well. In Ion, Socrates gives no hint of the disapproval of Homerthat he expresses in the Republic. The dialogue Ion suggests that Homer's Iliadfunctioned in the ancient Greek world as the Bible does today in the modernChristian world: as divinely inspired literature that can provide moralguidance, if only it can be properly interpreted.

Metaphysics

Metaphysics

"Platonism" is a term coined byscholars to refer to the intellectual consequences of denying, as Plato'sSocrates often does, the reality of the material world. In several dialogues,most notably the Republic, Socrates inverts the common man's intuition aboutwhat is knowable and what is real. While most people take the objects of theirsenses to be real if anything is, Socrates is contemptuous of people who thinkthat something has to be graspable in the hands to be real. In the Theaetetus,he says such people are eu amousoi (εὖἄμουσοι),an expression that means literally, "happily and without the muses"(Theaetetus 156a). In other words, such people live without the divineinspiration that gives him, and people like him, access to higher insights aboutreality.

Theoryof Forms

The theory of Forms (or theory of Ideas)typically refers to the belief that the material world as it seems to us is notthe real world, but only an "image" or "copy" of the realworld. In some of Plato's dialogues, this is expressed by Socrates, who spokeof forms in formulating a solution to the problem of universals. The forms,according to Socrates, are archetypes or abstract representations of the manytypes of things, and properties we feel and see around us that can only beperceived by reason (Greek: λογική).(That is, they are universals.) In other words, Socrates was able to recognizetwo worlds: the apparent world, which constantly changes, and an unchanging andunseen world of forms, which may be the cause of what is apparent.

Epistemology

Many have interpreted Plato as stating—evenhaving been the first to write—that knowledge is justified true belief, aninfluential view that informed future developments in epistemology. Thisinterpretation is partly based on a reading of the Theaetetus wherein Platoargues that knowledge is distinguished from mere true belief by the knowerhaving an "account" of the object of her or his true belief(Theaetetus 201c–d). And this theory may again be seen in the Meno, where it issuggested that true belief can be raised to the level of knowledge if it isbound with an account as to the question of "why" the object of thetrue belief is so (Meno 97d–98a). Many years later, Edmund Gettier famouslydemonstrated the problems of the justified true belief account of knowledge.That the modern theory of justified true belief as

knowledge which Gettieraddresses is equivalent to Plato's is accepted by some scholars but rejected byothers.[50] Plato himself also identified problems with the justified truebelief definition in the Theaetetus, concluding that justification (or an"account") would require knowledge of differentness, meaning that thedefinition of knowledge is circular.

Thestate

Plato's philosophical views had manysocietal implications, especially on the idea of an ideal state or government.There is some discrepancy between his early and later views. Some of the mostfamous doctrines are contained in the Republic during his middle period, aswell as in the Laws and the Statesman.

Plato, through the words of Socrates,asserts that societies have a tripartite class structure corresponding to theappetite/spirit/reason structure of the individual soul. Theappetite/spirit/reason are analogous to the castes of society.

`Productive(Workers) — the laborers,carpenters, plumbers, masons, merchants, farmers, ranchers, etc. Thesecorrespond to the "appetite" part of the soul.

`Protective (Warriors or Guardians) — thosewho are adventurous, strong and brave; in the armed forces. These correspond tothe "spirit" part of the soul.

`Governing (Rulers or Philosopher Kings) —those who are intelligent, rational, self-controlled, in love with wisdom, wellsuited to make decisions for the community. These correspond to the"reason" part of the soul and are very few.

In the Timaeus, Plato locates the parts ofthe soul within the human body: Reason is located in the head, spirit in thetop third of the torso, and the appetite in the middle third of the torso, downto the navel.

According to this model, the principles ofAthenian democracy (as it existed in his day) are rejected as only a few arefit to rule. Instead of rhetoric and persuasion, Plato says reason and wisdomshould govern. As Plato puts it:

"Until philosophers rule as kings orthose who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequatelyphilosophies, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide,while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively areforcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils,... nor,I think, will the human race." (Republic 473c-d)

Plato describes these "philosopherkings" as "those who love the sight of truth" (Republic 475c)and supports the idea with the analogy of a captain and his ship or a doctor andhis medicine. According to him, sailing and health are not things that everyoneis qualified to practice by nature. A large part of the Republic then addresseshow the educational system should be set up to produce these philosopher kings.

Unwrittendoctrines

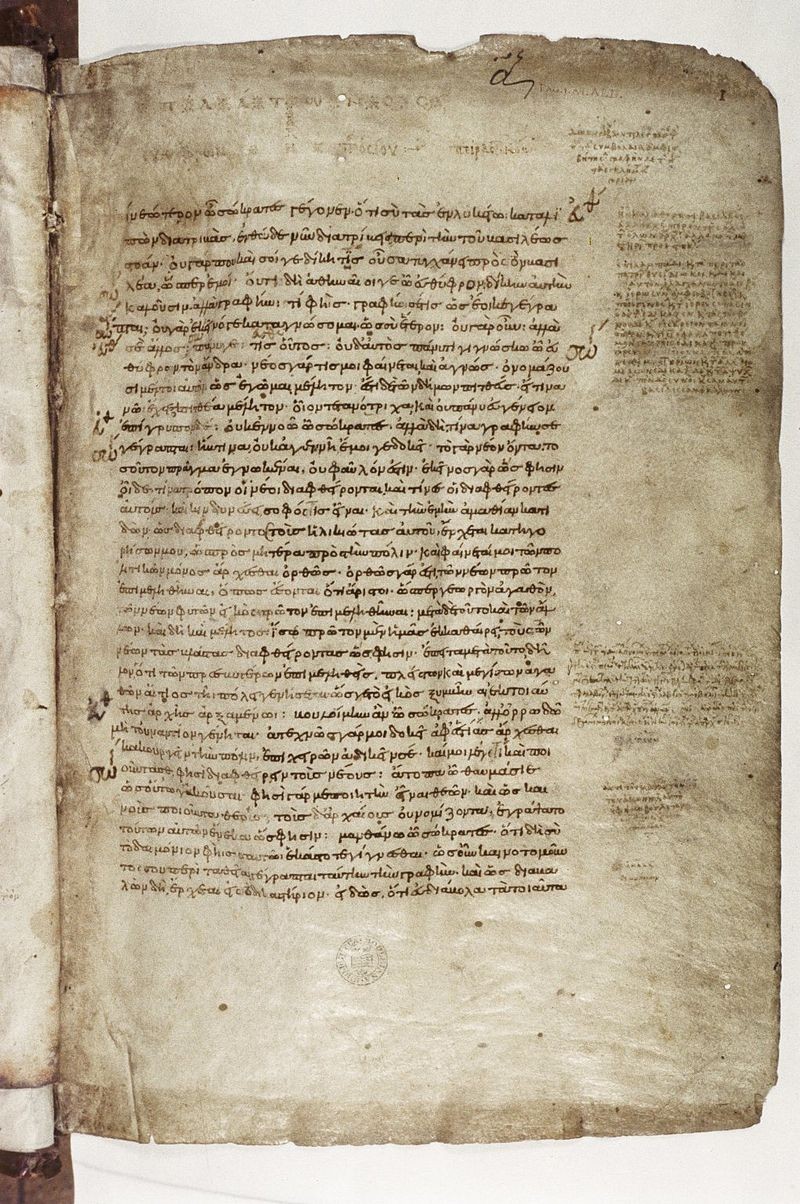

For a long time, Plato's unwrittendoctrine[65][66][67] had been  controversial. Many modern books on Plato seem todiminish its importance; nevertheless, the first important witness who mentionsits existence is Aristotle, who in his Physics (209 b) writes: "It istrue, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e. in Timaeus] of theparticipant is different from what he says in his so-called unwritten teachings(ἄγραφα δόγματα)."The term "ἄγραφα δόγματα"literally means unwritten doctrines and it stands for the most fundamentalmetaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some sayonly to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from thepublic. The importance of the unwritten doctrines does not seem to have beenseriously questioned before the 19th century.

controversial. Many modern books on Plato seem todiminish its importance; nevertheless, the first important witness who mentionsits existence is Aristotle, who in his Physics (209 b) writes: "It istrue, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e. in Timaeus] of theparticipant is different from what he says in his so-called unwritten teachings(ἄγραφα δόγματα)."The term "ἄγραφα δόγματα"literally means unwritten doctrines and it stands for the most fundamentalmetaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some sayonly to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from thepublic. The importance of the unwritten doctrines does not seem to have beenseriously questioned before the 19th century.

Dialectic

The role of dialectic in Plato's thought iscontested but there are two main interpretations: a type of reasoning and amethod of intuition. Simon Blackburn adopts the first, saying that Plato'sdialectic is "the process of eliciting the truth by means of questionsaimed at opening out what is already implicitly known, or at exposing thecontradictions and muddles of an opponent's position." A  similarinterpretation has been put forth by Louis Hartz, who suggests that elements ofthe dialectic are borrowed from Hegel. According to this view, opposingarguments improve upon each other, and prevailing opinion is shaped by thesynthesis of many conflicting ideas over time. Each new idea exposes a flaw inthe accepted model, and the epistemological substance of the debate continuallyapproaches the truth. Hartz's is a teleological interpretation at the core, inwhich philosophers will ultimately exhaust the available body of knowledge andthus reach "the end of history." Karl Popper, on the other hand,claims that dialectic is the art of intuition for "visualising the divineoriginals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the commonman's everyday world of appearances."

similarinterpretation has been put forth by Louis Hartz, who suggests that elements ofthe dialectic are borrowed from Hegel. According to this view, opposingarguments improve upon each other, and prevailing opinion is shaped by thesynthesis of many conflicting ideas over time. Each new idea exposes a flaw inthe accepted model, and the epistemological substance of the debate continuallyapproaches the truth. Hartz's is a teleological interpretation at the core, inwhich philosophers will ultimately exhaust the available body of knowledge andthus reach "the end of history." Karl Popper, on the other hand,claims that dialectic is the art of intuition for "visualising the divineoriginals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the commonman's everyday world of appearances."